The history of zirconium dates back to antiquity with the natural gem known as zircon, which has been known for millennia in Asia and the Middle East. The name zircon probably derives from the Persian zargun, meaning golden, referring to the yellow-brown color of some varieties of this mineral. However, the chemical composition of zircon and the existence of zirconium as a distinct element were not recognized until much later.

In 1789, the German chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1743-1817), famous for also discovering uranium and titanium, analyzed a sample of zircon from Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka). He succeeded in isolating a white oxide which he named zirconia (ZrO₂), recognizing that it contained a new element which he called zirconium. Klaproth did not manage to isolate the metal itself, but clearly established that zirconia was the oxide of an unknown element.

For more than three decades, chemists attempted unsuccessfully to isolate metallic zirconium. In 1824, the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779-1848), who had already discovered selenium, cerium, and thorium, succeeded in obtaining impure zirconium by reducing zirconium tetrafluoride (ZrF₄) with metallic potassium. The product obtained was a black powder containing zirconium mixed with impurities.

It was not until 1914 that the Dutch chemists Anton Eduard van Arkel and Jan Hendrik de Boer developed a process to obtain pure and ductile metallic zirconium. Their method, known as the van Arkel-de Boer process, involved the thermal decomposition of zirconium tetraiodide (ZrI₄) on a heated filament under vacuum. This process revealed for the first time the remarkable properties of pure zirconium.

The strategic importance of zirconium exploded with the development of nuclear energy in the 1940s and 1950s. Zirconium has an extremely low neutron capture cross-section, which means it absorbs very few neutrons. This property, combined with its excellent corrosion resistance and mechanical stability at high temperatures, made it the ideal material for nuclear reactor fuel cladding.

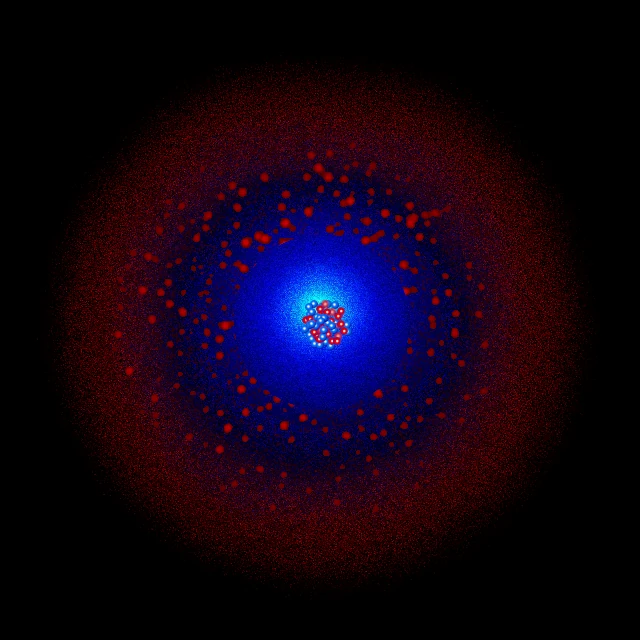

Zirconium (symbol Zr, atomic number 40) is a transition metal of group 4 of the periodic table. Its atom has 40 protons, usually 50 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{90}\mathrm{Zr}\)) and 40 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d² 5s².

Zirconium is a bright, gray-white metal, with an appearance similar to stainless steel. It has a density of 6.52 g/cm³, making it moderately heavy, similar to iron. Zirconium is relatively soft and ductile in its pure state, but its hardness increases considerably even with small amounts of impurities, particularly oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon.

Zirconium exhibits two allotropic forms. At room temperature up to 863 °C, it crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure, designated α-Zr. Above 863 °C up to its melting point, it adopts a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure, designated β-Zr. This allotropic transformation affects its mechanical properties and its ability to absorb hydrogen.

Zirconium melts at 1855 °C (2128 K) and boils at 4409 °C (4682 K), making it a refractory metal with a very wide liquid temperature range (about 2554 °C). This exceptional thermal stability contributes to its use in high-temperature applications.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zirconium-90 — \(\,^{90}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 50 | 89.904704 u | ≈ 51.45% | Stable | The most abundant isotope of natural zirconium, representing more than half of the total. |

| Zirconium-91 — \(\,^{91}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 51 | 90.905645 u | ≈ 11.22% | Stable | Second most abundant stable isotope. Used in nuclear research. |

| Zirconium-92 — \(\,^{92}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 52 | 91.905040 u | ≈ 17.15% | Stable | Third most abundant stable isotope of natural zirconium. |

| Zirconium-94 — \(\,^{94}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 54 | 93.906316 u | ≈ 17.38% | Stable | Fourth stable isotope, almost as abundant as zirconium-92. |

| Zirconium-96 — \(\,^{96}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 56 | 95.908276 u | ≈ 2.80% | ≈ 2.0 × 10¹⁹ years | Radioactive (β⁻β⁻). Extremely slow double beta decay, considered quasi-stable. |

| Zirconium-93 — \(\,^{93}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 53 | 92.906476 u | Synthetic | ≈ 1.53 × 10⁶ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Activation product in nuclear reactors. Long-lived radioactive waste. |

| Zirconium-95 — \(\,^{95}\mathrm{Zr}\,\) | 40 | 55 | 94.908043 u | Synthetic | ≈ 64.0 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Major fission product. Used as a tracer in research and industry. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Zirconium has 40 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d² 5s², or simplified: [Kr] 4d² 5s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(10) O(2).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic shielding.

N Shell (n=4): contains 10 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d². The two 4d electrons are valence electrons.

O Shell (n=5): contains 2 electrons in the 5s subshell. These electrons are also valence electrons.

Zirconium has 4 valence electrons: two 4d² electrons and two 5s² electrons. This [Kr] 4d² 5s² configuration is typical of group 4 transition metals and determines the chemistry of zirconium.

The most common and stable oxidation state of zirconium is +4, where it loses its four valence electrons to form the Zr⁴⁺ ion with the configuration [Kr] (isoelectronic with krypton). Zirconium dioxide (ZrO₂) or zirconia is the most important compound, extremely stable thermally and chemically. Zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl₄) is also a common compound of zirconium(IV).

Lower oxidation states exist but are much less stable. The +3 state appears in a few compounds such as zirconium trichloride (ZrCl₃), but these compounds are unstable and easily disproportionate. The +2 and +1 states are very rare and only exist in highly reactive or transient compounds.

The 0 oxidation state corresponds to metallic zirconium. Zirconium also forms important organometallic compounds, particularly with cyclopentadienyl ligands, used as catalysts in polymerization (modified Ziegler-Natta catalysts).

The moderate electronegativity of zirconium (1.33 on the Pauling scale) indicates that its bonds can be partially covalent, particularly in organometallic compounds, although most of its inorganic compounds are primarily ionic with the Zr⁴⁺ ion.

At room temperature, bulk zirconium is remarkably resistant to corrosion. It spontaneously forms a thin, adherent layer of zirconium oxide (ZrO₂) that passivates it against further oxidation. This oxide layer, only a few nanometers thick, is so effective that zirconium resists air, water, and even many acids and bases at ordinary temperatures.

Finely divided or powdered zirconium is pyrophoric, meaning it can spontaneously ignite in air due to the high surface-to-volume ratio that promotes rapid oxidation. The combustion of zirconium produces zirconia (ZrO₂) with intense light emission: Zr + O₂ → ZrO₂. Zirconium fires are difficult to extinguish because the metal can react with water, carbon dioxide, and even nitrogen at high temperatures.

Zirconium reacts vigorously with halogens to form tetrahalides: Zr + 2X₂ → ZrX₄ (where X = F, Cl, Br, I). Zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl₄) is a sublimable white solid used as a precursor for the production of metallic zirconium and organometallic compounds. The tetrafluoride (ZrF₄) is exceptionally stable.

At room temperature, zirconium resists most dilute acids due to its protective oxide layer. However, it is attacked by hydrofluoric acid (HF), which dissolves the oxide layer by forming soluble fluoride complexes: Zr + 6HF → H₂ZrF₆ + 2H₂. Hot, concentrated hydrochloric acid can also attack zirconium. Aqua regia solutions (HCl/HNO₃ mixture) also dissolve zirconium.

Zirconium reacts with hydrogen at high temperatures (300-400 °C) to form zirconium hydrides (ZrH₂, ZrH₃, ZrH₄), although the reaction is slow at room temperature due to the oxide layer. The absorption of hydrogen significantly embrittles zirconium, a phenomenon known as hydrogen embrittlement, which is a major concern in nuclear applications.

With nitrogen at high temperatures (above 700 °C), zirconium forms nitrides (ZrN, Zr₃N₄), which are very hard and refractory ceramics. With carbon at very high temperatures, it forms zirconium carbide (ZrC), one of the most refractory materials known, with a melting point of 3540 °C.

Zirconium plays an absolutely crucial role in the modern nuclear industry. More than 90% of the world's zirconium production is intended for nuclear applications, mainly in the form of alloys called Zircaloy (Zircaloy-2 and Zircaloy-4), which contain about 98% zirconium with small amounts of tin, iron, chromium, and nickel.

The fundamental property that makes zirconium indispensable in nuclear reactors is its extremely low neutron capture cross-section, about 0.18 barn for thermal neutrons. This means that zirconium absorbs very few neutrons, allowing a maximum of neutrons to participate in the nuclear fission chain reaction. This neutron transparency is essential for the efficiency and neutron economy of reactors.

Zirconium fuel cladding surrounds the uranium oxide pellets (UO₂) in the fuel assemblies of light water reactors (PWR and BWR). These claddings must withstand extreme conditions: high temperatures (300-350 °C), significant pressure, intense neutron flux, and prolonged contact with high-temperature water. Zirconium maintains its structural integrity under these conditions for several years of irradiation.

However, zirconium has a critical vulnerability at very high temperatures. Above 1200 °C, the oxidation reaction of zirconium with steam becomes exothermic and autocatalytic: Zr + 2H₂O → ZrO₂ + 2H₂. This reaction produces hydrogen gas that can accumulate and risk exploding. This mechanism played a major role in the serious nuclear accidents at Three Mile Island (1979), Chernobyl (1986), and Fukushima (2011).

After the Fukushima accident, intensive research was conducted to develop alternative cladding materials or protective coatings for zirconium to improve reactor safety in the event of a loss-of-coolant accident. Accident-tolerant fuels (ATF) incorporating chromium, molybdenum, or silicon carbide coatings are under study.

Zirconium dioxide (ZrO₂), commonly known as zirconia, is one of the most important ceramic oxides. Zirconia exists in several crystalline forms: monoclinic (stable at room temperature), tetragonal (stable between 1170-2370 °C), and cubic (stable above 2370 °C up to the melting point at 2715 °C).

Stabilized zirconia, obtained by adding yttrium oxide (Y₂O₃), magnesium (MgO), or calcium (CaO), maintains the cubic or tetragonal phase at room temperature. This yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) has exceptional properties: high mechanical strength, remarkable toughness, excellent wear resistance, chemical inertness, and biocompatibility.

Synthetic cubic zirconia, created by crystal growth from molten stabilized zirconia, is the main diamond simulant in jewelry. With a refractive index of 2.15-2.18 and high dispersion, cubic zirconia exhibits brilliance and fire similar to diamond, although slightly inferior. Its hardness of 8-8.5 on the Mohs scale makes it sufficiently durable for everyday use in jewelry, while being much less expensive than diamond.

In medicine, zirconia has become the material of choice for dental prostheses (crowns, bridges) and orthopedic implants (femoral heads of hip prostheses). Its natural ivory-white color, perfect biocompatibility, exceptional fracture resistance, and lack of corrosion make it an ideal material for these demanding biomedical applications.

Zirconia also exhibits ionic conductivity of oxygen at high temperatures, a property exploited in oxygen sensors (automotive lambda probes) and solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC). In these applications, O²⁻ ions migrate through the crystalline structure of zirconia, allowing the measurement of oxygen concentration or the production of electricity.

Zirconium is synthesized in stars mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. The five stable isotopes of zirconium are produced by this process, with minor contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers.

The cosmic abundance of zirconium is about 1.1×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it relatively rare in the universe. This modest abundance reflects its position far from the iron peak in the nuclear stability curve.

The mineral zircon (ZrSiO₄) plays an exceptional role in geochronology and planetary sciences. Zircon crystals are extremely resistant to chemical and physical weathering, surviving metamorphic and sedimentary processes. They incorporate uranium and thorium during their formation but exclude lead, making them ideal geological chronometers for uranium-lead (U-Pb) dating.

The oldest known terrestrial zircon crystals, discovered in the Jack Hills of Western Australia, have been dated to about 4.4 billion years, only 160 million years after the formation of the Earth. These ancient zircons provide valuable information about the conditions on the early Earth, suggesting the existence of continental crust and liquid water much earlier than previously thought.

The spectral lines of neutral zirconium (Zr I) and ionized zirconium (Zr II) are observable in the spectra of many stars, particularly those of spectral types F, G, and K. The analysis of these lines allows the determination of the abundance of zirconium in stellar atmospheres and the tracing of the chemical enrichment of galaxies over their evolution.

Excesses of zirconium have been detected in some chemically peculiar stars, particularly carbon stars and barium stars, which have been enriched in s-process elements by mass transfer from an evolved companion star. These observations confirm our understanding of the nucleosynthesis of heavy elements in binary star systems.

In meteorites, presolar zircons (grains formed in stellar environments before the formation of the solar system) exhibit characteristic isotopic anomalies that allow their specific stellar origin to be identified. The study of these grains provides direct information on the physical and chemical conditions prevailing in the stars where they formed.

N.B.:

Zirconium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.019% by mass (190 ppm), making it the 20th most abundant element in the crust, more abundant than copper, zinc, or lead. Zirconium is never found in its native state but always combined in minerals.

The main ore of zirconium is zircon (ZrSiO₄), a natural silicate containing about 67% ZrO₂. Zircon occurs as transparent to opaque tetragonal crystals, in various colors (colorless, yellow, brown, red, green) depending on impurities. Baddeleyite (natural ZrO₂) is another important but much rarer ore. The main zircon deposits are found in Australia, South Africa, China, India, and the United States.

Global production of zircon concentrate is about 1.5 million tons per year, mainly extracted from heavy mineral sands (placer deposits) where zircon accumulates through natural gravitational concentration. Australia dominates world production with about 37% of the total, followed by South Africa and China. Zircon is separated from other heavy minerals (ilmenite, rutile, monazite) by magnetic and electrostatic separation.

Metallic zirconium is produced mainly by the Kroll process, similar to that used for titanium. Zircon is first converted to zirconium tetrachloride (ZrCl₄) by chlorination, then ZrCl₄ is reduced with molten magnesium: ZrCl₄ + 2Mg → Zr + 2MgCl₂. The zirconium obtained in sponge form is then melted and purified by vacuum arc melting. For nuclear applications, additional purification is required to remove hafnium, an element chemically very similar to zirconium but with a high neutron capture cross-section.

Hafnium (element 72) always accompanies zirconium in natural ores due to their extreme chemical similarity (lanthanide contraction). Natural zirconium typically contains 1-4% hafnium. The separation of hafnium and zirconium is one of the most difficult operations in extractive metallurgy, requiring many cycles of liquid-liquid extraction or fractional distillation of the tetrachlorides. For nuclear-grade zirconium, the hafnium content must be reduced to less than 100 ppm.

The zirconium market is segmented between nuclear applications (high-purity zirconium metal, a highly specialized and regulated market) and ceramic applications (zirconia, a much broader market). The price of zircon concentrate ranges between 1000 and 2000 US dollars per ton depending on quality and market conditions. Nuclear-grade zirconium metal is much more expensive, with prices reaching several tens of dollars per kilogram.

Global demand for zirconium is steadily growing, driven by the expansion of nuclear energy in several countries (China, India, Russia), the growth of ceramic applications in dentistry and orthopedics, and the increasing use of zirconia in advanced electronics. Zirconium is considered a strategic material by several nations due to its importance for the nuclear industry.