Ytterbium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in low- to medium-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch). As a heavy lanthanide with an even atomic number (Z=70), it is efficiently produced by this process. Unlike lighter lanthanides such as europium, ytterbium shows a very low contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture), estimated at less than 10-15% of its solar abundance. This makes ytterbium, along with lutetium, one of the purest tracers of the s-process among rare earth elements.

The cosmic abundance of ytterbium is about 8.0×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about 4 times more abundant than thulium but 2 times less abundant than holmium. Due to its even atomic number, it follows the Oddo-Harkins rule and is more abundant than its odd neighbors (thulium-69 and lutetium-71). Its position at the end of the lanthanide series makes it an important indicator of the efficiency of the s-process in producing the heaviest elements.

Ytterbium is one of the preferred elements for studying the s-process in astrophysics. The ytterbium/europium (Yb/Eu) ratio in stars is a particularly sensitive indicator of the relative contribution of the s- and r-processes. A high Yb/Eu ratio is characteristic of stars enriched in s-process elements, such as barium stars. Ytterbium is also used to constrain nucleosynthesis models in AGB stars, as its relative abundance compared to other s-process elements (such as barium, lanthanum, or cerium) depends on the physical conditions (temperature, neutron density) in these stars.

Ytterbium has been detected in many stars, including metal-poor stars, thanks to its relatively accessible spectral lines (notably those of the Yb II ion). These measurements have made it possible to trace the history of s-process production in the Galaxy. In meteorites, ytterbium shows abundances similar to those of the Sun, but fine isotopic studies have revealed anomalies that provide information on the stellar sources that contributed to the solar nebula. Ytterbium is also used in geochemistry as a tracer of magmatic and metamorphic processes.

Ytterbium takes its name, like several other rare earths, from the Swedish village of Ytterby on the island of Resarö near Stockholm. Ytterby, which means "outer village" in Swedish, is famous for its feldspar quarry, which provided minerals containing many rare earths. Four elements bear names derived from Ytterby: yttrium (Y), terbium (Tb), erbium (Er), and ytterbium (Yb). Ytterbium thus shares this geographical origin with other elements discovered in the same ores.

Ytterbium was discovered in 1878 by the Swiss chemist Jean-Charles Galissard de Marignac (1817-1894), who also discovered gadolinium. While working on what was thought to be erbia (erbium oxide) from gadolinite from Ytterby, Marignac observed that this oxide actually contained two distinct rare earths. He isolated a new oxide, which he named "ytterbia," believing it to be the oxide of a new element. Marignac was an expert in crystallography and density measurements, techniques he used to distinguish ytterbia from erbia.

For several decades, Marignac's "ytterbia" was considered the oxide of a single element. However, in 1907, the French chemist Georges Urbain and independently the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach demonstrated that ytterbia actually contained two elements. Urbain named them neo-ytterbium and lutetium, while von Welsbach named them aldebaranium and cassiopeium. It was finally the names "ytterbium" for the more abundant element (formerly neo-ytterbium) and "lutetium" for the other that were internationally adopted. This separation was difficult because the two elements have extremely similar chemical properties.

Ytterbium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 3.0 ppm (parts per million), making it one of the rarest lanthanides, comparable to holmium and thulium. The main ores containing ytterbium are bastnasite ((Ce,La,Nd,Yb)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Yb,Th)PO₄), where it typically represents 0.1 to 0.5% of the total rare earth content, and xenotime (YPO₄), where it can be more concentrated. Ytterbium is also present in euxenite and gadolinite.

Global production of ytterbium oxide (Yb₂O₃) is about 50 to 100 tons per year, making it one of the least produced rare earths. Due to its rarity and high-value specialized applications, ytterbium is one of the most expensive rare earths, with typical prices ranging from 500 to 1,500 dollars per kilogram of oxide (with significant variations). China dominates production with over 90% of the global total.

Metallic ytterbium is produced mainly by metallothermic reduction of ytterbium fluoride (YbF₃) with metallic calcium in an inert argon atmosphere, or by reduction of the oxide with lanthanum. Global annual production of metallic ytterbium is only a few tons. Recycling of ytterbium is very limited due to the small quantities used, but could become more important with the development of laser applications and atomic clocks.

Ytterbium (symbol Yb, atomic number 70) is the fourteenth and penultimate element of the lanthanide series, belonging to the rare earths of the f-block of the periodic table. Its atom has 70 protons, usually 104 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{174}\mathrm{Yb}\)) and 70 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 6s². This configuration has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons), giving ytterbium particular stability and distinct chemical properties.

Ytterbium is a silvery, bright, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. It has a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure at room temperature, which is unusual among lanthanides, which generally adopt a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure. This FCC structure contributes to some of its distinctive physical properties. Ytterbium has the lowest density among lanthanides (6.90 g/cm³) and relatively high compressibility.

Ytterbium melts at 824 °C (1097 K) and boils at 1196 °C (1469 K). These melting and boiling points are the lowest of all lanthanides, similar to those of europium. Ytterbium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 798 °C, where its crystal structure changes from face-centered cubic (FCC) to body-centered cubic (BCC). Ytterbium is diamagnetic at room temperature (unlike most lanthanides, which are paramagnetic) due to its complete 4f¹⁴ electronic configuration, which has no unpaired electrons.

Ytterbium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, but oxidizes slowly to form Yb₂O₃. It oxidizes more rapidly when heated and burns to form the oxide: 4Yb + 3O₂ → 2Yb₂O₃. Ytterbium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form ytterbium(III) hydroxide Yb(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids. The metal must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere.

Melting point of ytterbium: 1097 K (824 °C).

Boiling point of ytterbium: 1469 K (1196 °C).

Crystal structure at room temperature: Face-centered cubic (FCC).

Density: 6.90 g/cm³ (the lowest among lanthanides).

Magnetic property: Diamagnetic (complete 4f configuration).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ytterbium-168 — \(\,^{168}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 98 | 167.933897 u | ≈ 0.13 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope, doubly magic (protons and neutrons in complete shells). |

| Ytterbium-170 — \(\,^{170}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 100 | 169.934761 u | ≈ 3.04 % | Stable | Stable isotope used as a target to produce the Tm-170 isotope for medicine. |

| Ytterbium-171 — \(\,^{171}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 101 | 170.936326 u | ≈ 14.28 % | Stable | Stable isotope with nuclear spin 1/2, used in optical lattice atomic clocks. |

| Ytterbium-172 — \(\,^{172}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 102 | 171.936382 u | ≈ 21.83 % | Stable | Stable isotope, one of the most abundant in the natural mixture. |

| Ytterbium-173 — \(\,^{173}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 103 | 172.938211 u | ≈ 16.13 % | Stable | Stable isotope with nuclear spin 5/2. |

| Ytterbium-174 — \(\,^{174}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 104 | 173.938862 u | ≈ 31.83 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope in nature (about 32%). |

| Ytterbium-176 — \(\,^{176}\mathrm{Yb}\,\) | 70 | 106 | 175.942572 u | ≈ 12.76 % | Stable | Heaviest stable isotope, representing about 13% of the natural mixture. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Ytterbium has 70 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell with 14 electrons. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(32) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 32 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴ 5d⁰. The completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) gives ytterbium its stability and diamagnetic character.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of ytterbium.

Ytterbium effectively has 16 valence electrons: fourteen 4f¹⁴ electrons and two 6s² electrons. Ytterbium exhibits two stable oxidation states: +2 and +3. The +3 state is the most common, where ytterbium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Yb³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹³. This ion is paramagnetic and exhibits luminescent properties.

The +2 state is particularly stable for ytterbium due to the complete 4f¹⁴ configuration of the Yb²⁺ ion (configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴). This full-shell configuration provides exceptional stability, similar to that of noble gases. Ytterbium(II) compounds such as YbI₂ (ytterbium diiodide), YbCl₂, and YbSO₄ are therefore relatively stable and less reducing than divalent compounds of other lanthanides. In aqueous solution, Yb²⁺ is a moderate reducer that slowly oxidizes to Yb³⁺ in the presence of air.

This ease of existing in two oxidation states makes ytterbium similar to europium in its chemical behavior. However, ytterbium(II) is even more stable than europium(II) due to the completely filled 4f subshell. This rich redox chemistry is exploited in certain catalytic and electrochemical applications.

Metallic ytterbium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin protective layer of Yb₂O₃. At high temperatures (above 200 °C), it oxidizes rapidly and burns to form the oxide: 4Yb + 3O₂ → 2Yb₂O₃. Ytterbium(III) oxide is a white solid with a cubic C-type rare earth structure. In fine powder form, ytterbium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Ytterbium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form ytterbium(III) hydroxide Yb(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Yb + 6H₂O → 2Yb(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous white solid with low solubility. As with other lanthanides, the reaction is not violent but is observable over time.

Ytterbium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides in the +3 state: 2Yb + 3F₂ → 2YbF₃ (white fluoride); 2Yb + 3Cl₂ → 2YbCl₃ (white chloride). Under appropriate conditions, it can also form ytterbium(II) dihalides: Yb + I₂ → YbI₂. Ytterbium dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids with the release of hydrogen and the formation of the corresponding Yb³⁺ salts: 2Yb + 6HCl → 2YbCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Ytterbium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperatures (300-400 °C) to form YbH₂ hydride, then YbH₃ at higher temperatures. With sulfur, it forms Yb₂S₃ sulfide. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperatures (>1000 °C) to form YbN nitride, and with carbon to form YbC₂ carbide. Ytterbium also forms many coordination complexes with organic ligands, especially in the +3 state.

The Yb³⁺ ion exhibits interesting luminescent properties in the near infrared. It has a simple electronic transition (²F₇/₂ → ²F₅/₂) around 980 nm, which is exploited in lasers and optical amplifiers. This transition has a broad absorption and emission spectrum, high quantum yield, and low loss due to spontaneous emission, making it an excellent active medium for high-power lasers. Yb³⁺ is also used as a sensitizer in some phosphorescent materials, transferring its energy to other lanthanide ions such as erbium or thulium.

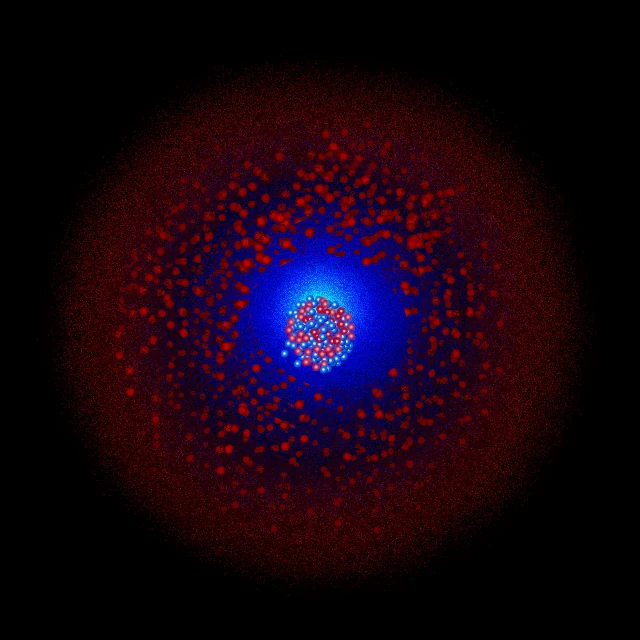

The most advanced and precise application of ytterbium is its use in optical lattice atomic clocks. These clocks use laser-cooled ytterbium-171 atoms trapped in an optical lattice created by interfering lasers. The transition used is the electronic transition ¹S₀ → ³P₀ of ytterbium-171 at a frequency of 518 THz (wavelength 578 nm), in the visible range. This transition is extremely narrow and insensitive to external perturbations, allowing exceptional stability and precision.

Ytterbium clocks are among the most precise ever developed. They achieve a relative stability on the order of 10⁻¹⁸, meaning they would lose only one second over more than the age of the universe (13.8 billion years). This extraordinary precision has applications in:

Yb:YAG lasers are high-power solid-state lasers that emit around 1030 nm. They have several advantages over more traditional Nd:YAG lasers:

Ytterbium-doped fiber lasers and amplifiers (YDFL, YDFA) are extremely important in telecommunications and industrial machining. They offer excellent beam quality, high power, high efficiency, and compactness. Ytterbium fiber amplifiers are used to amplify signals in optical communication networks. Ytterbium fiber lasers are used for metal cutting (especially in the automotive and aerospace industries) and marking.

Small amounts of ytterbium (generally less than 0.1%) are added to certain stainless steels to refine grain size and improve mechanical properties, particularly toughness and corrosion resistance. Ytterbium acts as a deoxidizer and modifies the formation of inclusions, leading to a finer and more uniform microstructure.

Ytterbium-based strain gauges exploit the property of certain ytterbium compounds to change their electrical resistance under mechanical stress. These sensors are used to measure deformations in critical structures (bridges, aircraft, pipelines) with high sensitivity and stability.

The isotope ytterbium-169 (¹⁶⁹Yb) is used as a portable gamma ray source for industrial non-destructive testing. Yb-169 emits low-energy gamma rays (mainly 63 keV, 110 keV, 130 keV, 177 keV, and 198 keV) that are ideal for inspecting light materials (aluminum, composites) and thin welds. Its half-life of 32 days is practical for industrial use.

Ytterbium(II) compounds, particularly ytterbium diiodide (YbI₂), are used as mild reducing agents in organic synthesis. They can perform selective reductions of certain functional groups without affecting other parts of the molecule. Metallic ytterbium is also used as a reducing agent in the preparation of other high-purity metals.

Ytterbium and its compounds have low chemical toxicity, comparable to other lanthanides. Soluble salts can cause skin, eye, and respiratory irritation. No severe acute toxicity or carcinogenic effects have been demonstrated. The LD50 (median lethal dose) of ytterbium salts in animals is similar to that of other rare earths (typically >500 mg/kg). Ytterbium has no known biological role.

Like other lanthanides, ytterbium preferentially accumulates in the liver and bones in case of exposure, with very slow elimination. General population exposure is extremely low, mainly limited to workers in the relevant industries.

For the Yb-169 isotope used in industrial radiation sources, radiation protection precautions are necessary. The low energy of the gamma rays facilitates shielding (a few millimeters of lead are sufficient), but precautions against external exposure are required. For Yb-171 used in atomic clocks, the activity is generally very low and does not pose a significant risk.

The environmental impacts specifically related to ytterbium are minimal due to the very small quantities produced and used. Recycling of ytterbium is limited but could become more important with the development of laser applications and atomic clocks. Recycling techniques would be similar to those for other rare earths. Waste containing radioactive isotopes of ytterbium (Yb-169, Yb-175) must be treated as low-level radioactive waste.

Occupational exposure occurs in rare earth production plants, research laboratories on atomic clocks, and industries using Yb lasers or Yb-169 sources. Standard precautions for metal dusts and radiation protection (where applicable) apply.