This nickname reflects thallium's triple nature: discovered spectroscopically in the shadow of industrial residues (its green spectral line emerging from waste); acting as a biological shadow by usurping potassium's place in cells with insidious, delayed-toxicity effects; and historically used as the "perfect" criminal poison, operating in the shadows due to its odorless, tasteless nature and delayed symptoms.

Thallium is a heavy element produced mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. It also has a significant contribution from the r-process (rapid capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Its relatively low atomic number (Z=81) and position in the periodic table make its synthesis relatively efficient, but its cosmic abundance remains modest. It is one of the "heavy" elements whose presence in a star or galaxy reveals successive generations of nucleosynthesis.

The cosmic abundance of thallium is about 1.0×10⁻¹² that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it as rare as gold or platinum. Its presence in stellar spectra is difficult to detect due to the weakness of its lines. On Earth, it is highly dispersed and almost never forms its own minerals. It is found in trace amounts in the sulfides of many metals (pyrite, blende, galena), which is why it is often a byproduct of zinc, lead, and copper metallurgy.

Thallium has two stable isotopes, \(^{203}\mathrm{Tl}\) and \(^{205}\mathrm{Tl}\). Variations in the \(^{205}\mathrm{Tl}/^{203}\mathrm{Tl}\) ratio are studied in isotopic geochemistry. Thallium exhibits strong incompatible lithophile behavior in magmatic processes, concentrating in liquids and rocks of the upper crust. Its isotopes can be fractionated by redox and adsorption processes, providing a new tool for tracing the cycle of elements in oceans, sediments, and hydrothermal systems. Thallium is thus used to study the evolution of ocean oxygenation in geological history.

Like many volatile elements, thallium shows a deficit in chondritic meteorites and terrestrial planets compared to solar abundance. This is explained by its moderately volatile nature: it did not fully condense in the inner regions of the protoplanetary disk where the rocky planets formed. The study of thallium isotopic ratios in meteorites helps to understand the temperature and pressure conditions during the formation of the solar system.

The name "thallium" comes from the Greek θαλλός (thallós), meaning "young shoot" or "green twig". This name was given by its discoverer, Sir William Crookes, in 1861, because of the intense bright green spectral line he observed in the emission spectrum of dust from a sulfuric acid production chamber. This spectral line (at 535 nm) is so characteristic that it dominated the spectrum, evoking the color of a new bud.

Thallium was discovered independently in 1861 by two scientists:

A priority dispute followed, but today both men are credited with the discovery.

Crookes produced the first sample of metallic thallium in 1862 by electrolysis of a thallium salt solution. Lamy, for his part, produced enough to determine several of its physical properties. The extreme toxicity of thallium and its compounds quickly became apparent, which limited its study and caused several fatal accidents among pioneering chemists.

There are no primary thallium mines. Thallium is always recovered as a byproduct of the metallurgy of other metals:

The main producing countries are China, Russia, and Kazakhstan. Global annual production is very low, on the order of 10 to 15 tons, reflecting its rarity and the limited (and strictly controlled) demand for this dangerous element. Its price is high due to recovery and purification costs.

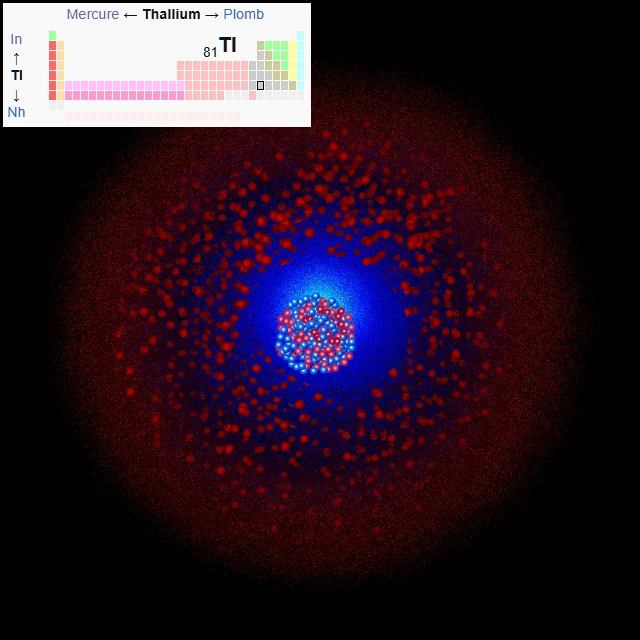

Thallium (symbol Tl, atomic number 81) is a poor metal of the p-block, located in group 13 of the periodic table, with boron, aluminum, gallium, and indium. It is the heaviest stable element in this group. Its atom has 81 protons, usually 123 or 124 neutrons (for the isotopes \(^{203}\mathrm{Tl}\) and \(^{205}\mathrm{Tl}\)), and 81 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p¹. It therefore has three valence electrons (6s² 6p¹).

Thallium is a bluish-gray, soft, malleable metal that tarnishes rapidly in air, taking on a grayish tint. It is soft enough to be scratched with a fingernail.

Thallium melts at 304 °C (577 K) and boils at 1473 °C (1746 K). Its moderate melting point facilitated its historical metallurgical processing.

Thallium is a fairly reactive metal. It tarnishes in air, forming a mixture of oxide (Tl₂O) and nitride. It reacts slowly with water (especially if the water contains dissolved oxygen) to form the hydroxide TlOH, which is a strong and soluble base. It dissolves easily in mineral acids (sulfuric and nitric acids) to give the corresponding Tl(I) or Tl(III) salts. It forms amalgams with mercury.

Density: 11.85 g/cm³.

Melting point: 577 K (304 °C).

Boiling point: 1746 K (1473 °C).

Crystal structure: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p¹.

Main oxidation states: +1 and +3.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thallium-203 — \(^{203}\mathrm{Tl}\) | 81 | 122 | 202.972344 u | ≈ 29.52 % | Stable | Stable isotope. Used as a target to produce lead-203 (for nuclear medicine) or as a tracer in research. |

| Thallium-205 — \(^{205}\mathrm{Tl}\) | 81 | 124 | 204.974427 u | ≈ 70.48 % | Stable | Major stable isotope. Reference isotope for geochemical measurements. |

| Thallium-204 (artificial/natural) | 81 | 123 | 203.97386 u | Trace | 3.78 years | Radioactive β⁻ (97%) and electron capture (3%). Used as a beta source in thickness gauges and detectors. Present in trace amounts in the environment (product of uranium decay). |

| Thallium-201 (artificial) | 81 | 120 | 200.9708 u | 0 % | 73.1 hours | Radioactive by electron capture. Major medical isotope used in myocardial scintigraphy (cardiac imaging). Emits gamma rays of 135 and 167 keV. Produced by irradiation of thallium-203 in a cyclotron. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Thallium has 81 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p¹ has a 6p subshell with only one electron. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(3), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p¹.

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 3 electrons (6s² 6p¹).

Thallium has 3 valence electrons (6s² 6p¹). It exhibits a fascinating chemical duality with two stable oxidation states: +1 (thallium(I) or thallous) and +3 (thallium(III) or thallic).

This duality (+1 stable) is surprising for a heavy element in group 13 (where Al, Ga, In prefer the +3 state). It is explained by the inert pair effect: the 6s² electron pair is very stable and reluctant to participate in bonding, leaving the chemistry of the 6p¹ electron to predominate.

Metallic thallium tarnishes slowly in moist air, forming a mixture of gray-black thallium(I) oxide (Tl₂O) and hydroxide (TlOH). When heated in air, it burns with an emerald green flame (characteristic of Tl⁺ ions) to form mainly Tl₂O, as well as some mixed oxides and thallium(III) oxide (Tl₂O₃) on the surface.

Thallium reacts directly with halogens to form halides. With chlorine, it forms TlCl (insoluble, white) or, in excess chlorine, Tl(III) complexes. With sulfur, it gives thallium(I) sulfide (Tl₂S), which is black.

The extreme toxicity of thallium(I) is mainly explained by its ionic mimicry with potassium (K⁺). Both ions have similar ionic radii (Tl⁺: 164 pm, K⁺: 152 pm). Thallium can thus usurp the place of potassium in many essential biological processes:

Once inside the cell, thallium cannot be effectively expelled and accumulates, causing irreversible damage.

Poisoning can be acute (single high dose) or chronic (repeated low doses). Symptoms usually appear 12 to 48 hours after ingestion.

Poisoning is often fatal without treatment. Neurological sequelae (neuropathy, chronic pain) are common among survivors.

Treatment is a medical emergency and is based on:

Due to its solubility, lack of odor and taste, and the delay in the onset of symptoms, thallium sulfate was nicknamed "inheritance powder" and was used in many criminal poisonings in the 20th century. Industrial accidents (e.g., cement plants using contaminated ores) and accidental food poisonings (treated seeds) have also caused deaths.

The main sources of thallium in the environment are:

Thallium is relatively mobile in the environment. As Tl⁺, it is soluble in water and can contaminate groundwater. It is poorly biodegradable. Some plants (such as cabbage) can accumulate thallium from the soil. Bioaccumulation in the food chain is less pronounced than for mercury, but the risk to ecosystems and humans via contaminated drinking water and food is real.

Due to its high toxicity, thallium is strictly regulated:

Any waste containing thallium must be treated as hazardous and toxic. Industrial processes generating thallium must capture and recycle this element to prevent its dispersion.

Research focuses on:

Thallium remains an emblematic element of the dangers posed by toxic heavy metals, reminding us of the need for constant vigilance in their management throughout their life cycle, from extraction to disposal.