Praseodymium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with significant contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Praseodymium is a typical product of light lanthanide nucleosynthesis, although its production is slightly less efficient than that of neighboring cerium.

The cosmic abundance of praseodymium is about 1.8×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about 65 times less abundant than cerium in the universe. This relatively low abundance is explained by praseodymium's less favorable position on the nuclear stability curve. The single isotope Pr-141 has an odd number of protons and a magic number of neutrons (82), giving it substantial stability.

The spectral lines of neutral (Pr I) and ionized (Pr II) praseodymium are difficult to observe in stellar spectra due to its low cosmic abundance. Praseodymium is nevertheless used as a complementary tracer for the chemical enrichment of lanthanides in stars. The praseodymium/neodymium ratio in metal-poor stars provides constraints on the relative contributions of the s- and r-processes in galactic history.

Some chemically peculiar stars, particularly Ap stars and s-process enriched giants, show slightly increased praseodymium abundances compared to normal stars. These variations are attributed to s-process nucleosynthesis in AGB stars or atmospheric diffusion processes in strongly magnetic Ap stars. Spectroscopic observation of praseodymium in these objects requires large-aperture telescopes and high-resolution spectrometers due to the weakness of the lines.

Praseodymium takes its name from the Greek words prasios (green) and didymos (twin), referring to the characteristic green color of its salts and the fact that it was isolated from didymium, a mixture of rare earths previously considered a single element. The name literally means "green twin," distinguishing praseodymium from neodymium, the "new twin."

In 1885, the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach (1858-1929) demonstrated that didymium, discovered in 1841 by Carl Gustaf Mosander, was not a single element but a mixture of two distinct elements. Through repeated fractional crystallizations of nitrates, Welsbach succeeded in separating didymium into two components: praseodymium, forming green salts, and neodymium, forming purple-pink salts. This remarkable discovery demonstrated the exceptional experimental skill required to separate rare earths with almost identical chemical properties.

The isolation of pure praseodymium metal proved extremely difficult due to its high reactivity and persistent neodymium impurities. The first samples of praseodymium metal were obtained in the early 20th century by electrolytic reduction of molten chloride or chemical reduction with metallic calcium. It was not until the development of modern ion exchange and solvent extraction techniques in the 1950s-1960s that the production of high-purity praseodymium became economically viable.

Praseodymium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 9.2 ppm, making it the 39th most abundant element on Earth, comparable to boron. Although much less abundant than cerium, praseodymium is more abundant than silver, gold, or platinum. The main ores containing praseodymium are bastnäsite ((Ce,La,Pr,Nd)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Pr,Nd,Th)PO₄), in which praseodymium accounts for about 4-5% of the rare earth content.

Global production of praseodymium oxides is about 4000 to 5000 tons per year. China dominates production with about 85-90% of the world total, followed by the United States, Australia, and Myanmar. This extreme geographical concentration makes praseodymium a strategically critical element, particularly for the high-performance permanent magnet industry.

Praseodymium metal is produced mainly by reducing praseodymium oxide (Pr₆O₁₁) with metallic calcium at high temperature in an inert atmosphere, or by electrolysis of molten praseodymium chloride in a molten salt bath. Global annual production of praseodymium metal is about 1000 to 1500 tons. Recycling of praseodymium from used magnets remains limited, accounting for less than 1% of total supply, although recycling efforts are intensifying with rising prices and supply concerns.

Praseodymium (symbol Pr, atomic number 59) is the third element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the f-block rare earths of the periodic table. Its atom has 59 protons, usually 82 neutrons (for the only stable isotope \(\,^{141}\mathrm{Pr}\)) and 59 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f³ 6s².

Praseodymium is a soft, ductile, and malleable silvery-white metal with a slight yellow-green tint. It oxidizes rapidly in air, forming a characteristic green oxide layer that gradually disintegrates, offering no protection to the underlying metal. Praseodymium crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure at room temperature, transitioning to a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure at high temperature (about 795 °C).

Praseodymium melts at 931 °C (1204 K) and boils at 3520 °C (3793 K). Its density is 6.77 g/cm³, similar to that of cerium. Praseodymium is a good conductor of electricity and heat, with electrical conductivity about 10 times lower than that of copper. Praseodymium exhibits interesting magnetic properties: it is paramagnetic at room temperature and becomes antiferromagnetic below 25 K.

Praseodymium is a highly reactive metal, oxidizing rapidly in humid air and spontaneously igniting in the form of fine shavings or powder. It reacts vigorously with water, producing praseodymium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Praseodymium must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation. The reactivity of praseodymium is typical of light lanthanides and slightly higher than that of neodymium.

Melting point of praseodymium: 1204 K (931 °C).

Boiling point of praseodymium: 3793 K (3520 °C).

Praseodymium is paramagnetic at room temperature and becomes antiferromagnetic below 25 K.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praseodymium-141 — \(\,^{141}\mathrm{Pr}\,\) | 59 | 82 | 140.907653 u | 100 % | Stable | Only natural isotope of praseodymium, monoisotopic. Magic number of neutrons (82). |

| Praseodymium-142 — \(\,^{142}\mathrm{Pr}\,\) | 59 | 83 | 141.910045 u | Synthetic | ≈ 19.12 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Used in nuclear research and as a tracer in experimental medicine. |

| Praseodymium-143 — \(\,^{143}\mathrm{Pr}\,\) | 59 | 84 | 142.910817 u | Synthetic | ≈ 13.57 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Significant fission product, used in nuclear fission studies. |

| Praseodymium-144 — \(\,^{144}\mathrm{Pr}\,\) | 59 | 85 | 143.913305 u | Synthetic | ≈ 17.28 minutes | Radioactive (β⁻). Decay product of Ce-144, rapid transitional step to stable Nd-144. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

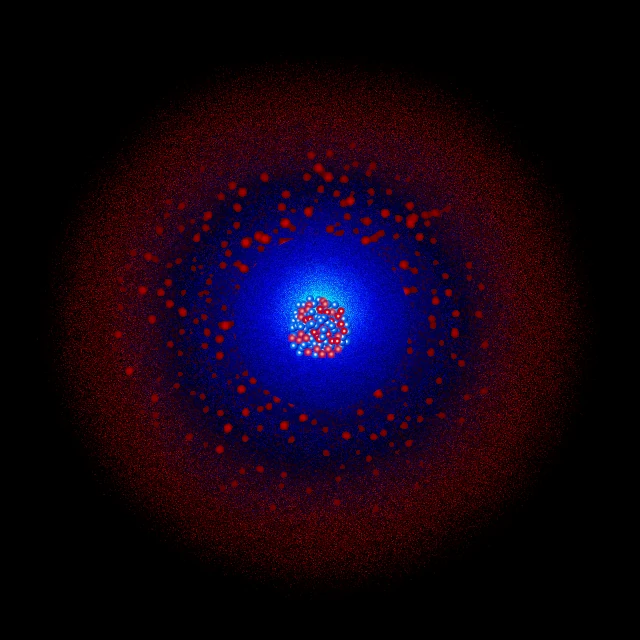

Praseodymium has 59 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f³ 6s², typical of light lanthanides where the 4f subshell is progressively filled. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(21) P(2), or fully: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f³ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N Shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable and complete structure.

O Shell (n=5): contains 21 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f³ 5d⁰. The three 4f electrons characterize the chemistry of praseodymium.

P Shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of praseodymium.

Praseodymium effectively has 5 valence electrons: three 4f³ electrons and two 6s² electrons. The dominant oxidation state is +3, characteristic of all lanthanides, where praseodymium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Pr³⁺ ion with the configuration [Xe] 4f². This Pr³⁺ ion is responsible for the characteristic green color of praseodymium salts and solutions.

The +4 state also exists but is much less stable than for neighboring cerium. Pr⁴⁺ (configuration [Xe] 4f¹) is a powerful oxidant and only exists in a few solid compounds such as Pr₆O₁₁ oxide (a mixture of Pr³⁺ and Pr⁴⁺) and PrF₄ fluoride. In aqueous solutions, Pr⁴⁺ is extremely unstable and quickly reduces to Pr³⁺ by oxidizing water. The chemistry of praseodymium is therefore essentially the chemistry of the Pr³⁺ ion.

Praseodymium compounds with the +2 oxidation state have been synthesized under extreme conditions (solid-phase halides), but these compounds are extraordinarily unstable and oxidize instantly. The +2 state has no practical relevance in praseodymium chemistry.

Praseodymium is very reactive with oxygen and oxidizes rapidly in air, forming a characteristic green layer of praseodymium(III) oxide (Pr₂O₃) that cracks and flakes, continuously exposing fresh metal to oxidation. At high temperatures, praseodymium burns vigorously in air with a bright white flame, producing a mixed oxide Pr₆O₁₁ containing both Pr³⁺ and Pr⁴⁺: 6Pr + 11O₂ → 2Pr₆O₁₁. Fine praseodymium powder is pyrophoric and spontaneously ignites at room temperature.

Praseodymium reacts slowly with cold water but rapidly with hot water or steam, producing green praseodymium(III) hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas: 2Pr + 6H₂O → 2Pr(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. This reaction accelerates considerably at high temperatures and can become violent with boiling water. Praseodymium(III) hydroxide is a moderately strong base that easily precipitates from aqueous solutions as a pale green gelatinous solid.

Praseodymium reacts vigorously with halogens to form colored trihalides: 2Pr + 3Cl₂ → 2PrCl₃ (green). Praseodymium(IV) fluoride PrF₄ can be obtained by direct fluorination at high temperature. Praseodymium dissolves easily in acids, even diluted ones, with the release of hydrogen: 2Pr + 6HCl → 2PrCl₃ + 3H₂↑, producing characteristic green solutions of Pr³⁺.

Praseodymium reacts with sulfur to form praseodymium sulfide (Pr₂S₃), with nitrogen at high temperature to form nitride (PrN), with carbon to form carbide (PrC₂), and with hydrogen to form hydride (PrH₂ or PrH₃). All Pr³⁺ compounds exhibit a characteristic green coloration, a distinctive property that allows easy identification of praseodymium.

The intense green color of praseodymium(III) compounds comes from f-f electronic transitions within the 4f² configuration. These transitions are partially allowed by spin-orbit coupling and produce characteristic absorption bands in the visible spectrum. Praseodymium-doped glasses and crystals strongly absorb in the yellow, preferentially transmitting green and blue, which produces the distinctive green tint. This optical property is exploited in the production of colored glasses and specialized optical filters.

The dominant application of praseodymium, accounting for about 50-60% of global consumption, is its use in Nd-Fe-B (neodymium-iron-boron) type permanent magnets. Praseodymium is partially substituted for neodymium in the formulation of these magnets, typically in proportions of 10-30% praseodymium to 70-90% neodymium, thus forming (Nd,Pr)-Fe-B magnets.

Praseodymium significantly improves the thermal stability of Nd-Fe-B magnets, increasing their maximum operating temperature (Curie temperature) and reducing the negative temperature coefficient that causes pure neodymium magnets to lose magnetic strength when heated. This property is crucial for automotive applications, particularly electric and hybrid vehicle motors that operate at high temperatures (120-180 °C).

(Nd,Pr)-Fe-B magnets are essential for electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators, hard drives, industrial servomotors, missile guidance systems, and many defense and aerospace applications. A typical electric vehicle contains 0.5-2 kg of light rare earths (neodymium and praseodymium combined) in its motor. Partial substitution of neodymium with praseodymium also allows cost optimization when the relative prices of the two elements fluctuate, with praseodymium generally being 10-30% cheaper than neodymium for equivalent performance.

Praseodymium has been used for over a century as a coloring agent to produce intense yellowish-green glasses and ceramic enamels. Praseodymium salts added to molten glass in concentrations of 0.5-3% produce a range of shades from pale yellow-green to deep emerald green, depending on the concentration and composition of the glass matrix. This coloration is stable at high temperatures and resistant to UV fading, unlike organic dyes.

An important technical application of praseodymium is the production of protective glasses for welders, glassblowers, and metallurgists. Didymium glasses (praseodymium-neodymium mixture) strongly absorb the intense yellow wavelengths emitted by sodium in flames and electric arcs (sodium D line at 589 nm), significantly reducing glare and protecting workers' eyes. These glasses transmit about 70-80% of total visible light while specifically blocking the bothersome yellow lines.

Praseodymium is used as a dopant in optical fibers to create praseodymium-doped fiber amplifiers (PDFA) operating in the 1.3 μm band, an important region for optical telecommunications. Although less common than erbium-doped amplifiers (EDFA), PDFA are essential for certain specialized applications requiring amplification in this wavelength band. Praseodymium is also used in doped YAG laser crystals to generate specific wavelengths in the visible and near-infrared.

Praseodymium accounts for about 4-5% of the typical composition of mischmetal, a light rare earth alloy used primarily for lighter flints and as a metallurgical additive. Although minor compared to cerium (45-50%) and lanthanum (25%), praseodymium contributes to the pyrophoric properties of the alloy and its ability to desulfurize steels.

Beyond mischmetal, praseodymium is used in various specialized metal alloys. Praseodymium-nickel alloys (PrNi₅) exhibit interesting magnetic properties and are studied for hydrogen storage. Magnetostrictive alloys containing praseodymium are used in ultrasonic transducers and precision actuators. Praseodymium also improves the mechanical properties of certain aluminum and magnesium alloys when added in small amounts (0.1-0.5%).

Praseodymium and its compounds exhibit low to moderate toxicity, similar to other light lanthanides. Soluble praseodymium compounds can cause skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation upon direct exposure. Inhalation of praseodymium dust can cause lung irritation, although no specific cases of praseodymium pneumoconiosis have been documented in exposed workers.

Ingestion of soluble praseodymium compounds can cause transient gastrointestinal disorders, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Toxicological studies in animals indicate that praseodymium primarily accumulates in the liver, spleen, and bone skeleton during chronic exposures. At high doses, praseodymium can interfere with calcium metabolism and disrupt liver function, although toxic thresholds are relatively high.

The toxicity of praseodymium is comparable to that of cerium and neodymium, and significantly lower than that of toxic transition elements such as lead or cadmium. Praseodymium does not exhibit significant bioaccumulation in food chains and degrades or is eliminated relatively quickly from exposed organisms. No carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic effects have been demonstrated for praseodymium in available studies.

Environmental exposure to praseodymium mainly comes from rare earth mining, metallurgical refining, and recycling of permanent magnets. Praseodymium concentrations in soils near rare earth mines can reach several tens of ppm, 3-5 times natural background levels. Runoff waters from mining sites may also contain high concentrations of dissolved praseodymium.

Occupational exposure standards for praseodymium are not specifically established in most countries, but general recommendations for soluble rare earth compounds typically set exposure limits at 5-10 mg/m³ for respirable dust. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does not consider praseodymium a priority pollutant. The ecotoxicological impacts of praseodymium on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems remain moderate at typical environmental concentrations, although effects on certain sensitive species have been documented at high concentrations (>100 mg/L).