Antimony is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with minor contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. The two stable isotopes of antimony are produced by these processes.

The cosmic abundance of antimony is extremely low, about 3×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the rarest elements in the universe. This extreme rarity is explained by several factors: antimony has an odd number of protons (Sb, Z = 51), making it less stable than even-numbered elements, and it lies in an unfavorable region of the nuclear stability curve.

The spectral lines of neutral antimony (Sb I) and ionized antimony (Sb II) are extremely difficult to observe in stellar spectra due to the very low cosmic abundance of this element. Nevertheless, traces of antimony have been detected in a few chemically peculiar stars ultra-enriched in s-process elements, allowing the study of nucleosynthesis processes in evolved AGB stars.

Antimony has been known since antiquity, although it was often confused with other substances. The Egyptians used natural antimony sulfide (stibnite, Sb₂S₃) as early as 3000 BCE as black eye cosmetic (kohl). The Babylonians and Assyrians also used antimony in cosmetics and dyes. The name antimony probably derives from the Arabic ithmid or al-'ithmid, referring to stibnite.

A popular etymology sometimes attributes the name to a Latin combination anti-monachum (against monks), suggesting that antimony was toxic to monks, but this origin is likely apocryphal. The chemical symbol Sb comes from the Latin stibium, the ancient name for stibnite.

Metallic antimony was known in the Middle Ages, although its preparation was shrouded in alchemical mystery. The German Benedictine monk Basile Valentin (1394-1450) described (uncertain dates, 15th century) in his alchemical writings various preparations of antimony and its properties. His work "The Triumphant Chariot of Antimony" (published around 1604) detailed methods of purification and medicinal uses of antimony.

The recognition of antimony as a distinct chemical element occurred gradually in the 18th century. Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794) included it in his list of chemical elements in 1789. Antimony was produced industrially in significant quantities from the 19th century, mainly for metallurgy and pigments.

Antimony is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.2 ppm, making it relatively rare, about 10 times rarer than tin but 10 times more abundant than silver. The main antimony ore is stibnite (Sb₂S₃), containing about 71% antimony. Secondary ores include valentinite (Sb₂O₃), senarmontite (cubic Sb₂O₃), and kermesite (Sb₂S₂O).

Global antimony production is about 150,000 to 180,000 tons per year. China dominates production with about 60-70% of the world total, followed by Russia, Tajikistan, Bolivia, and South Africa. This extreme concentration of production in China makes antimony a highly strategic and vulnerable material to geopolitical disruptions.

Antimony is considered a critical material by the European Union, the United States, and other major economies due to its importance for fire safety and batteries, combined with the extreme geographic concentration of its production. Antimony recycling is modest, accounting for about 10-15% of supply, mainly recovered from used lead-acid batteries. The recycling rate is limited by the dilution of antimony in alloys and technical difficulties in recovery.

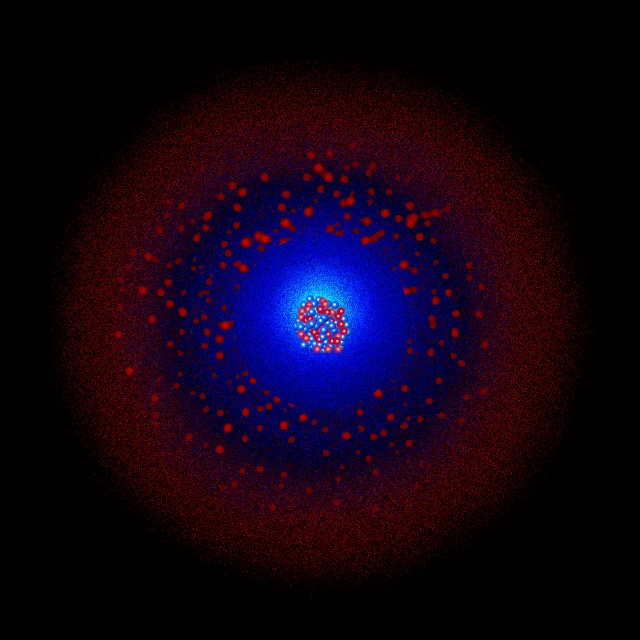

Antimony (symbol Sb, atomic number 51) is a metalloid in group 15 of the periodic table, along with nitrogen, phosphorus, arsenic, and bismuth. Its atom has 51 protons, usually 70 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{121}\mathrm{Sb}\)), and 51 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p³.

Antimony is a shiny silver-gray solid with a metallic luster, but its properties are intermediate between metals and non-metals, justifying its classification as a metalloid. It has a density of 6.69 g/cm³, making it moderately heavy. Antimony crystallizes in a rhombohedral structure similar to that of arsenic. It is brittle and friable, easily powdered, and cannot be rolled or drawn.

Antimony melts at 631 °C (904 K) and boils at 1587 °C (1860 K). A unique and valuable property of antimony is that it expands upon solidification (volumetric expansion of about 1.7%), a rare behavior shared with water, bismuth, and gallium. This property was historically exploited for the manufacture of sharp and precise printing type.

Antimony is a poor conductor of heat and electricity, a characteristic property of metalloids. It has an electrical resistance about 400 times higher than that of copper. Antimony resists atmospheric corrosion well at room temperature but oxidizes slowly in humid air.

Melting point of antimony: 904 K (631 °C).

Boiling point of antimony: 1860 K (1587 °C).

Antimony expands by about 1.7% upon solidification, a rare and valuable property.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimony-121 — \(\,^{121}\mathrm{Sb}\,\) | 51 | 70 | 120.903815 u | ≈ 57.21% | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope of antimony, representing more than half of the total. |

| Antimony-123 — \(\,^{123}\mathrm{Sb}\,\) | 51 | 72 | 122.904214 u | ≈ 42.79% | Stable | Second stable isotope of antimony, representing more than two-fifths of the total. |

| Antimony-124 — \(\,^{124}\mathrm{Sb}\,\) | 51 | 73 | 123.905935 u | Synthetic | ≈ 60.2 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Activation product in nuclear reactors, used as a tracer. |

| Antimony-125 — \(\,^{125}\mathrm{Sb}\,\) | 51 | 74 | 124.905253 u | Synthetic | ≈ 2.76 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Fission and activation product, used in industrial radiography. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Antimony has 51 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p³, or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p³. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(5).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O shell (n=5): contains 5 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p³. These five electrons are the valence electrons of antimony.

Antimony has 5 valence electrons: two 5s² electrons and three 5p³ electrons. The main oxidation states are -3, +3, and +5. The +3 state is the most common, where antimony loses its three 5p³ electrons, appearing in compounds such as antimony trioxide (Sb₂O₃) and antimony trichloride (SbCl₃).

The +5 state exists in more oxidized compounds such as antimony pentoxide (Sb₂O₅) and antimony pentachloride (SbCl₅), but these compounds are less stable than those of antimony(III). The -3 state appears in metallic antimonides (such as GaSb, InSb) where antimony acts as an electron acceptor, forming the Sb³⁻ ion. Metallic antimony corresponds to the oxidation state 0.

Antimony is relatively stable in air at room temperature, oxidizing slowly to form a thin protective oxide layer. At high temperatures (above 400 °C), antimony burns in air with a bright white flame, forming antimony trioxide (Sb₂O₃), which is released as white smoke: 4Sb + 3O₂ → 2Sb₂O₃. This white smoke was historically used to create theatrical effects.

Antimony reacts with halogens to form trihalides or pentahalides: 2Sb + 3Cl₂ → 2SbCl₃ (trichloride) or 2Sb + 5Cl₂ → 2SbCl₅ (pentachloride). Antimony trichloride is a fuming hygroscopic liquid used in chemical synthesis. Antimony resists non-oxidizing acids but dissolves in concentrated nitric acid and aqua regia.

With molten strong bases, antimony reacts to form antimonates. Antimony(III) sulfide (Sb₂S₃), the natural mineral stibnite, is an important compound with a dark gray metallic color. It was historically used as a pigment, cosmetic, and medicinal remedy.

The dominant application of antimony, representing about 60% of global demand, is antimony trioxide (Sb₂O₃) used as a synergist for halogenated flame retardants. Although antimony trioxide is not itself an effective flame retardant, it acts in synergy with brominated or chlorinated compounds to significantly inhibit the combustion of polymeric materials.

The mechanism involves the formation of volatile antimony trihalides (SbCl₃, SbBr₃) at high temperatures, which interfere with the radical reactions of the flame in the gas phase, effectively extinguishing the fire. This antimony-halogen combination is particularly effective and economical, allowing compliance with fire safety standards for plastics, textiles, foams, and electronic equipment.

A typical television contains 5-10 grams of antimony trioxide in its plastic components, a computer 3-5 grams, creating massive demand. However, environmental and health concerns about halogenated flame retardants (toxicity, bioaccumulation, dioxin production during incineration) have led to progressive restrictions in certain applications, affecting the demand for antimony.

The second major application of antimony is as a hardener in lead alloys for lead-acid batteries. The addition of 2-5% antimony to lead significantly increases its hardness, mechanical strength, and castability, essential properties for the positive grids of batteries that must withstand corrosion and mechanical stress for years.

Lead-antimony batteries offer better performance at high temperatures and extended lifespan compared to antimony-free batteries. However, they suffer from faster self-discharge and greater water consumption (hydrolysis), requiring regular maintenance. Modern vehicle batteries often use lead-calcium alloys without antimony to reduce maintenance.

Industrial batteries, heavy-duty starter batteries, telecommunications, and traction batteries (forklifts, submarines) continue to predominantly use lead-antimony alloys for their superior performance. This application represents about 20-25% of global antimony demand.

Antimony and its compounds exhibit moderate to high toxicity depending on the chemical form. Antimony trioxide (Sb₂O₃) is classified as possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Exposure occurs mainly through inhalation of dust in metallurgical and processing industries.

Acute exposure to antimony causes irritation of the eyes, skin, and respiratory tract, nausea, and vomiting. Chronic exposure can cause pulmonary (pneumoconiosis), cardiovascular, and dermatological problems. The effects are similar to those of arsenic, although generally less severe.

Antimony accumulates in the environment, particularly in soils near mines and smelters. Contamination of water by antimony from industrial sources and leaching of waste poses problems in some regions. Drinking water standards generally set the limit at 5-6 μg/L.