Radon is a gaseous element continuously produced in the Earth's crust by the radioactive decay of radium, itself derived from the uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232 chains. It is the only naturally radioactive noble gas under normal conditions. Three natural isotopes are significant, each corresponding to these chains:

Radon-222 formed in radium-containing minerals can, depending on soil porosity and water content, diffuse to the surface and be released into the atmosphere. This flux, called radon exhalation, varies significantly depending on geology (granitic and uranium-rich shales > sedimentary rocks), season, atmospheric pressure, and humidity. Measuring this flux is used in geophysics for:

Once in the atmosphere, radon-222 (an inert gas) is transported by winds. Since it decays with a known half-life, its decrease with distance from its continental source (oceans produce very little) allows the study of air mass mixing times between continents and oceans. In oceans, dissolved radon (produced by radium in sediments) serves as a tracer for vertical mixing processes and air-sea exchanges.

The name "radon" is derived from radium, its direct parent in the decay chain. The isotope \(^{222}\mathrm{Rn}\) was initially called "radium emanation" or simply "emanation" (denoted Em) by its discoverers, as it "emanated" from radium. Later, when isotopes from thorium and actinium were discovered, they were named thoron (Tn) and actinon (An), respectively. The generic name "radon" (symbol Rn) for element 86 was officially adopted in 1923.

Radon-222 was discovered in 1900 by the German physicist Friedrich Ernst Dorn. While studying radium compounds newly discovered by the Curies, he noticed that radium emitted a radioactive gas. He demonstrated that this gas, which he called "radium emanation," was itself radioactive and transformed into other solid elements. This discovery was crucial for understanding radioactive decay series.

In 1908, the Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay (already discoverer of the noble gases argon, krypton, xenon, and neon) and his assistant Robert Whytlaw-Gray succeeded in isolating radon, measuring its density, and proving it was the heaviest of the known noble gases. They managed to condense enough to observe its emission spectrum, confirming its status as an element. Ramsay received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 for his work on inert gases, even before the discovery of radon.

As early as the 1920s, radon was suspected of causing the high incidence of lung cancer among uranium miners (notably in the Joachimsthal mines in Czechoslovakia and later in New Mexico). However, it was not until the 1980s that epidemiological studies (such as those on American miners) firmly established the link between radon exposure and lung cancer. In the 1990s, awareness spread to domestic risk, transforming radon from a scientific curiosity into a major public health issue.

Radon is present everywhere, but its concentrations vary greatly.

There is no "production" of radon per se; it is constantly generated by natural decay and must be managed where it accumulates.

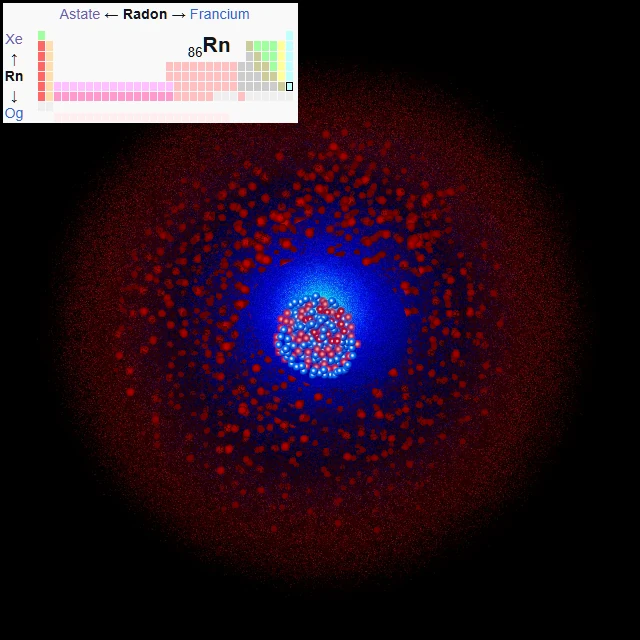

Radon (symbol Rn, atomic number 86) is an element of group 18, the noble gases (or rare gases). It is the heaviest and only naturally radioactive member of this group under normal conditions (oganesson, Z=118, is synthetic). Its atom has 86 protons and, depending on the isotope, 131 to 150 neutrons. The isotope \(^{222}\mathrm{Rn}\) has 136 neutrons. Its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁶, with a complete p valence shell (6 electrons), making it a chemically inert gas.

Radon is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless noble gas.

In solid form, radon has a yellow-orange color due to its radioactivity.

Radon melts at 202 K (-71 °C) and boils at 211 K (-61.7 °C). It can be liquefied relatively easily by cooling.

As a noble gas, radon is extremely inert. However, due to its large size and high polarizability, it is the most reactive noble gas. Theoretical calculations predict it could form a few unstable compounds, such as radon fluoride (RnF₂) and possibly oxides or clathrate complexes. In practice, only solid-state compounds, highly unstable and radioactive, have been obtained in minute quantities (clathrates with water or hydrocarbons). Its chemistry has little practical application.

State (20°C, 1 atm): Colorless gas.

Density (gas, 0°C): 9.73 g/L (8.1 x air).

Melting point: 202 K (-71 °C).

Boiling point: 211 K (-61.7 °C).

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁶.

Radioactivity: Main isotope \(^{222}\mathrm{Rn}\), α, T½=3.82 days.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Parent chain | Half-life / Decay mode | Remarks / Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radon-222 — \(^{222}\mathrm{Rn}\) | 86 | 136 | 222.017578 u | Uranium-238 (4n+2) | 3.8235 days (α) | Most important isotope. Half-life long enough to migrate from soil and accumulate in buildings. Mainly responsible for domestic health risk. |

| Radon-220 — \(^{220}\mathrm{Rn}\) (Thoron) | 86 | 134 | 220.011394 u | Thorium-232 (4n) | 55.6 seconds (α) | Very short half-life, limiting its accumulation away from the source. Mainly dangerous in industries processing thorium-rich materials (monazite sands, ceramics). |

| Radon-219 — \(^{219}\mathrm{Rn}\) (Actinon) | 86 | 133 | 219.009480 u | Uranium-235 (4n+3) | 3.96 seconds (α) | Negligible for public health due to its ultra-short half-life and low abundance of U-235 (0.72%). |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Radon has 86 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁶ has a completely filled valence shell (6p), giving it great chemical stability and noble gas character. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(8), or fully: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁶.

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 8 electrons (6s² 6p⁶).

Radon has 8 valence electrons in its outer shell (6s² 6p⁶), achieving the stable octet configuration. This saturated electronic structure makes it extremely reluctant to form classical covalent bonds. Its first ionization potential is relatively low for a noble gas (10.75 eV), but still too high for easy chemistry. Any attempt to form compounds (such as RnF₂) requires very strong oxidants like fluorine, and the resulting compounds are thermodynamically unstable and decompose rapidly.

This inertia is crucial for its environmental behavior: once formed in the soil, radon does not react with minerals or water; it diffuses freely as an atomic gas. In the lungs, it does not chemically interact with tissues; its danger is purely radiological.

The radon gas itself, once inhaled, is largely exhaled. The danger comes from its solid and radioactive decay products:

These particles (often charged) attach to ambient aerosols or dust. When inhaled, they can deposit in the respiratory tract, especially in the bronchi. Their alpha and beta decay inside lung tissue directly irradiates epithelial cells, causing DNA damage that can lead to cancer.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classifies radon as a certain human carcinogen. It is the second leading cause of lung cancer after smoking, and the leading cause among non-smokers. It is estimated that about 3 to 14% of lung cancers worldwide are attributable to radon, corresponding to tens of thousands of deaths annually. The risk is multiplicative with smoking: a smoker exposed to radon has a much higher risk of lung cancer than the sum of individual risks.

Health authorities set levels above which corrective actions are recommended:

Average outdoor concentrations are typically 5 to 15 Bq/m³. Indoors, they can range from less than 10 to over 10,000 Bq/m³ in the most affected areas.

The goal is to reduce radon concentration. Techniques, ranked by effectiveness and cost, are:

Many countries have established radon potential maps based on geology and measurements. In France, the IRSN has published a municipal map classifying communes into 3 potential categories. These maps are used to prioritize information actions and monitoring obligations (schools, workplaces in high-potential areas).

The radon issue is a perfectly identifiable and manageable environmental health problem. Current challenges are:

Radon, an invisible and natural gas, perfectly illustrates how a geological phenomenon can have a direct health impact on the population, and how science and regulation can combine to mitigate this risk.