Hafnium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in low- to medium-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch). As a heavy element with an even atomic number (Z=72), it is efficiently produced by this process. Hafnium also shows a significant contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. Models estimate that about 60-70% of solar hafnium comes from the s-process, and 30-40% from the r-process, making it a mixed-production element.

The cosmic abundance of hafnium is about 1.5×10⁻¹² times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it slightly more abundant than tungsten (Z=74) but less abundant than zirconium (Z=40), its chemical congener. Hafnium has several stable isotopes, the most abundant being hafnium-180 (35.1%). An interesting isotope is hafnium-176, which is radiogenic (it decays into lutetium-176 with a half-life of 37.8 billion years) and is used in geochronology.

The lutetium-176/hafnium-176 isotopic system (¹⁷⁶Lu → ¹⁷⁶Hf) is one of the most important chronometers in geochemistry and cosmochemistry. With a half-life of 37.8 billion years (slightly longer than the age of the universe), it allows dating events throughout Earth's and the solar system's history. The Hf/Lu ratio varies between different geological reservoirs (continental crust, mantle) because these two elements have distinct geochemical behaviors: lutetium is more "compatible" (remains in the mantle during partial melting) while hafnium is more "incompatible" (enters the magma). This allows tracing the formation and evolution of the continental crust.

In meteorites and lunar samples, hafnium isotopes provide crucial information on the early formation and differentiation of planetary bodies. The Hf-W (hafnium-tungsten) system is particularly important: hafnium-182 (radioactive, half-life of 8.9 million years) decays into tungsten-182. Since hafnium is lithophile (binds to silica) and tungsten is siderophile (binds to iron), their ratio evolves differently during the formation of a planet's metallic core. By measuring tungsten-182 anomalies, the formation of Earth's core and the early evolution of the solar system can be dated.

The name hafnium comes from Hafnia, the Latin name for the city of Copenhagen (Denmark). This name was chosen to honor the city where the element was discovered, following the tradition of naming elements after geographical locations. The discovery of hafnium is particularly interesting as it illustrates the application of nascent atomic physics principles to chemistry.

The existence of hafnium was predicted in 1913 by the English physicist Henry Moseley (1887-1915) thanks to his famous law, which established a relationship between the frequency of an element's characteristic spectral lines and its atomic number. By studying the spectra of elements, Moseley noticed a gap corresponding to the element with atomic number 72, located between lutetium (Lu, Z = 71) and tantalum (73). This theoretical prediction stimulated research to find this missing element.

Hafnium was discovered in 1923 by the Dutch physicist Dirk Coster (1889-1950) and the Hungarian chemist George de Hevesy (1885-1966) at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen. Using X-ray spectroscopy (Moseley's method), they analyzed zirconium minerals and detected the characteristic spectral lines of element 72. They succeeded in separating the new element from zirconium and named it hafnium. This discovery was the first to be guided by atomic theory and confirmed Niels Bohr's predictions about the electronic structure of elements.

Separating hafnium from zirconium was and remains a major technical challenge, as these two elements are chemically very similar—probably the most difficult pair to separate in the entire periodic table. They have almost the same atomic and ionic radius and form analogous compounds. Early methods used repeated fractional crystallizations of complex fluorides or phosphates. Today, industrial separation mainly uses solvent extraction with organic solvent mixtures.

Hafnium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 3.0 ppm (parts per million), making it as abundant as uranium or beryllium. There are no specific hafnium ores; it is always associated with zirconium in zircon (ZrSiO₄) and baddeleyite (ZrO₂) ores, where the Hf/Zr ratio is about 1-4% (i.e., 10,000 to 40,000 ppm of Hf in Zr). Due to this close association, hafnium production is always a byproduct of zirconium production.

Global production of hafnium metal is about 50 to 100 tons per year. The main producer is France (Orano, formerly Areva), followed by the United States, China, and Russia. Due to separation difficulties and specialized applications, hafnium is relatively expensive, with typical prices ranging from 500 to 1,500 dollars per kilogram for the metal, and much more for high-purity compounds. Demand is mainly driven by the nuclear industry and microelectronics.

Hafnium (symbol Hf, atomic number 72) is the first element in the series of transition metals of the 6th period, located in group 4 (formerly IVB) of the periodic table, along with titanium, zirconium, and rutherfordium. Its atom has 72 protons, usually 108 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{180}\mathrm{Hf}\)) and 72 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d² 6s². This configuration completes the 4f subshell and places two electrons in the 5d subshell, characteristic of transition metals.

Hafnium is a silvery-gray, shiny, ductile, and corrosion-resistant metal. It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature, identical to that of zirconium. Hafnium has a very high melting point (2233 °C), good mechanical strength, and excellent corrosion resistance due to the formation of a protective oxide layer of HfO₂. It is a good conductor of heat and electricity for a refractory metal.

Hafnium melts at 2233 °C (2506 K) and boils at 4603 °C (4876 K). These extremely high temperatures make it an interesting refractory material. Hafnium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 1760 °C where its crystal structure changes from hexagonal close-packed (HCP) to body-centered cubic (BCC). The most remarkable nuclear property of hafnium is its exceptionally high thermal neutron absorption cross-section (about 104 barns on average for the natural isotopic mixture), about 600 times higher than that of its congener zirconium. This property is crucial for its nuclear applications.

Hafnium is chemically very similar to zirconium, to the point that it was difficult to distinguish them for more than a century. In air, it forms a protective oxide layer of HfO₂ that protects it from further oxidation. It reacts with halogens, nitrogen, carbon, boron, and sulfur at high temperatures. Hafnium resists most acids and bases but dissolves in hydrofluoric acid. Its chemistry is mainly that of the +4 oxidation state, although a few compounds of lower states exist.

Melting point of hafnium: 2506 K (2233 °C).

Boiling point of hafnium: 4876 K (4603 °C).

Thermal neutron absorption cross-section: ~104 barns (600× that of Zr).

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

Main oxidation state: +4.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hafnium-174 — \(\,^{174}\mathrm{Hf}\,\) | 72 | 102 | 173.940046 u | ≈ 0.16 % | 2.0×10¹⁵ years | Alpha radioactive with extremely long half-life. Considered stable for most applications. |

| Hafnium-176 — \(\,^{176}\mathrm{Hf}\,\) | 72 | 104 | 175.941409 u | ≈ 5.26 % | Stable | Stable isotope, final product of lutetium-176 decay (Lu-Hf dating system). |

| Hafnium-177 — \(\,^{177}\mathrm{Hf}\,\) | 72 | 105 | 176.943221 u | ≈ 18.60 % | Stable | Stable isotope, one of the most abundant in the natural mixture. |

| Hafnium-178 — \(\,^{178}\mathrm{Hf}\,\) | 72 | 106 | 177.943699 u | ≈ 27.28 % | Stable | Stable isotope, the most abundant in nature. |

| Hafnium-179 — \(\,^{179}\mathrm{Hf}\,\) | 72 | 107 | 178.945816 u | ≈ 13.62 % | Stable | Important stable isotope. |

| Hafnium-180 — \(\,^{180}\mathrm{Hf}\,\) | 72 | 108 | 179.946550 u | ≈ 35.08 % | Stable | Major stable isotope, representing about 35% of natural hafnium. |

N.B.:

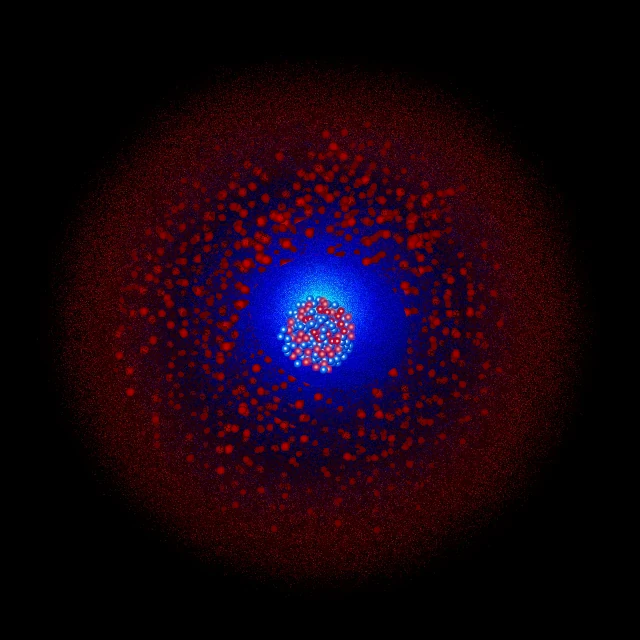

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Hafnium has 72 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d² 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and two electrons in the 5d subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(32) P(4), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d² 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 32 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴ 5d². The completely filled 4f subshell and the two 5d electrons give hafnium its transition metal properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 4 electrons in the 6s² and 5d² subshells (although 5d belongs to the n=5 shell).

Hafnium effectively has 4 valence electrons: two 6s² electrons and two 5d² electrons. Hafnium mainly exhibits the +4 oxidation state in its stable compounds. In this state, hafnium loses its two 6s and two 5d electrons to form the Hf⁴⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴. This ion has a completely filled 4f subshell and is diamagnetic.

Hafnium can also form compounds in lower oxidation states (+3, +2, +1, 0, and even -2), but these are much less stable and less common than Hf(IV) compounds. Hafnium(III) compounds, such as HfCl₃, are strongly reducing. The chemistry of hafnium is therefore dominated by the +4 state, where it closely resembles zirconium(IV) but with subtle differences due to the "lanthanide contraction" which makes the ionic radius of Hf⁴⁺ (78 pm) slightly smaller than that of Zr⁴⁺ (79 pm), despite the higher atomic mass.

This extreme chemical similarity between Hf⁴⁺ and Zr⁴⁺ is explained by their identical electronic configuration ([Kr] for Zr⁴⁺ and [Xe] 4f¹⁴ for Hf⁴⁺) and their almost identical ionic radii. The main differences are related to nuclear properties (neutron absorption) and some physical properties (density, melting point).

Hafnium metal is relatively stable in air at room temperature due to the formation of a thin protective oxide layer of HfO₂. At high temperatures (above 400 °C), it oxidizes rapidly: Hf + O₂ → HfO₂. Hafnium(IV) oxide is a very stable, refractory (melting point 2758 °C), and chemically inert white solid. It is used as a ceramic material and as a high-κ dielectric in microelectronics. In fine powder form, hafnium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Hafnium resists corrosion by water and water vapor up to high temperatures, making it interesting for nuclear applications. It dissolves slowly in hydrofluoric acid (HF) with the formation of fluoride complexes: Hf + 6HF → H₂[HfF₆] + 2H₂. It resists dilute hydrochloric, sulfuric, and nitric acids but is attacked by hot concentrated acids. Like zirconium, it resists bases well.

Hafnium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding tetrahalides: Hf + 2F₂ → HfF₄ (white fluoride); Hf + 2Cl₂ → HfCl₄ (white chloride). It reacts with nitrogen at high temperature (>800 °C) to form hafnium nitride HfN, with carbon to form hafnium carbide HfC (one of the most refractory materials known, melting point ~3890 °C), and with boron to form hafnium boride HfB₂. These compounds exhibit exceptional mechanical and thermal properties.

The most remarkable property of hafnium is its exceptionally high thermal neutron absorption cross-section (about 104 barns on average for the natural isotopic mixture). This property is about 600 times higher than that of its congener zirconium (0.185 barns). Several hafnium isotopes contribute to this absorption:

This property, combined with good mechanical strength and excellent resistance to corrosion by water and steam, makes hafnium an ideal material for control rods in pressurized water reactors (PWR).

In a nuclear reactor, control rods regulate the chain reaction by absorbing excess neutrons. They are inserted or removed from the core to maintain reactivity at the desired level and to shut down the reactor if necessary. The material of the control rods must have a high neutron absorption cross-section, good mechanical strength, excellent resistance to corrosion and radiation, and must not produce problematic long-lived isotopes.

Hafnium has a unique combination of properties that make it the material of choice for control rods in pressurized water reactors (PWR):

Hafnium control rods are typically made of Hf alloys (with about 2-4% Zr, Sn, Fe, Cr, Ni) or hafnium carbide (HfC). They are clad in a compatible material (often zirconium). A typical PWR contains several dozen control rods, each containing 10 to 50 kg of hafnium. The lifetime of the rods is several years (typically 10-20 years), after which they are replaced and stored as radioactive waste.

Used control rods are highly radioactive (mainly due to activation products such as Hf-181, half-life 42.4 days, and other isotopes). They are first stored in the reactor's spent fuel pools, then packaged for long-term storage. Hafnium itself does not present major long-term radiotoxicity problems because its stable isotopes are not radioactive, and the radioactive isotopes produced have relatively short half-lives.

In microprocessors, the size of transistors has continued to decrease according to Moore's law. Traditionally, the gate of MOS transistors was insulated from the channel by a thin layer of silicon dioxide (SiO₂). However, when the thickness of SiO₂ becomes less than 2 nm (about 5 atoms), undesirable quantum effects appear: current leakage due to tunneling, increased power consumption, and loss of transistor control.

To overcome this problem, the industry has adopted dielectric materials with a high dielectric constant (high-κ). These materials allow the same capacitance (and thus the same transistor control) with a greater physical thickness, thereby reducing tunneling leakage. Hafnium oxide (HfO₂) has become the material of choice for technology nodes from 45 nm onwards (introduced by Intel in 2007).

The introduction of HfO₂ (and other hafnium-based materials) has allowed the miniaturization of transistors to continue beyond the limits imposed by SiO₂. Today, virtually all advanced microprocessors (CPU, GPU) and memories use hafnium-based dielectrics. HfO₂ layers are deposited by ALD (Atomic Layer Deposition) with thicknesses on the order of 1-3 nm. Doped variants (such as HfSiO, HfSiON, HfZrO) are also used to optimize properties.

HfO₂ also exhibits ferroelectric properties when doped with zirconium, silicon, or yttrium. This ferroelectricity is exploited in FeRAM (Ferroelectric RAM) and in ferroelectric field-effect transistors (FeFET). In addition, HfO₂ alloys with other oxides are being studied for phase-change memories (PCRAM).

Hafnium is used as an alloying element (typically 1-3%) in nickel-based superalloys for gas turbines. It improves several critical properties:

Gas turbines used in aircraft (jet engines) and power plants (gas turbines for peak electricity production) operate at extreme temperatures (often >1000 °C) where the mechanical properties of materials are pushed to their limits. The addition of hafnium allows for higher operating temperatures, thus improving the efficiency and lifespan of turbines. Turbine blades made of nickel superalloys containing hafnium are among the most critical and highly stressed components.

Hafnium carbide (HfC) and hafnium nitride (HfN) are among the most refractory materials known:

These materials are used for coatings on high-performance cutting tools, components for very high temperature furnaces, and space propulsion systems (thermal shields, rocket engine nozzles). Hafnium boride (HfB₂) is also being studied for hypersonic applications due to its extreme stability at high temperatures.

Hafnium and its compounds have low chemical toxicity, comparable to that of zirconium. Soluble compounds can cause skin and respiratory irritation. No severe acute toxicity or carcinogenic effects have been demonstrated. Hafnium metal and its oxides are considered biologically inert. As with all fine metal powders, inhalation of dust should be avoided.

Natural hafnium is not significantly radioactive. However, in nuclear reactors, the hafnium in control rods becomes radioactive through neutron activation, producing mainly hafnium-181 (half-life 42.4 days, gamma and beta emitter). Used rods must therefore be handled with radiation protection precautions. After a few years of decay, the activity becomes low enough to allow simpler packaging and storage.

The main environmental impact is related to the production of zirconium, of which hafnium is a byproduct. The extraction of zircon and its transformation into zirconium metal generate chemical waste (acids, solvents) and mining residues. The separation of hafnium from zirconium by solvent extraction uses chemicals that must be managed properly. However, since the quantities produced are relatively small (a few tens to hundreds of tons per year), the overall impact is limited compared to other industrial metals.

Hafnium recycling is mainly practiced for production scrap and manufacturing waste. Hafnium from used nuclear control rods is generally not recycled due to radioactivity and high reprocessing costs. However, hafnium could theoretically be separated and reused, which could become interesting if prices were to rise significantly or if resources became more constrained.

Occupational exposure occurs in zirconium/hafnium production plants, manufacturers of nuclear and electronic components, and nuclear power plants. Standard precautions for metal dusts apply. In the nuclear industry, additional precautions are necessary for activated hafnium.