Radium is a crucial intermediate element in the uranium-238 decay chain (4n+2 series). It is produced by the alpha decay of thorium-230 (ionium) and itself decays into radon-222 by alpha emission. Several radium isotopes exist in different chains, but the most important is radium-226 (half-life 1600 years), which is in secular equilibrium with uranium-238 in ancient minerals. Its presence and relative abundance are therefore directly related to the uranium content of the environment.

The uranium-thorium/radium isotopic system is used to date geological processes on timescales ranging from a few years to about 500,000 years. The \(^{226}\mathrm{Ra}/^{230}\mathrm{Th}\) ratio is particularly useful for dating marine carbonates (corals, concretions) and recent oceanic sediments. Since radium is more soluble than thorium, it is leached from continents and transported to the oceans. Measuring its activity in sediment cores allows the reconstruction of sedimentation rates and past climate changes.

Radium has four natural isotopes with different half-lives (\(^{223}\mathrm{Ra}\), 11.4 days; \(^{224}\mathrm{Ra}\), 3.66 days; \(^{226}\mathrm{Ra}\), 1600 years; \(^{228}\mathrm{Ra}\), 5.75 years). This "string" of isotopes with decreasing timescales makes it an ideal tracer for processes at different scales:

Radium-226 present in soils and rocks is the direct source of radon-222, a radioactive gas that migrates into buildings. The radium content of a soil is therefore the main determinant of the radon potential of a region.

The name "radium" was chosen by its discoverers, Pierre and Marie Curie, and derives from the Latin word "radius", meaning "ray". This name celebrates the most striking property of the new element: its intense radioactivity, which manifests itself by the emission of invisible but detectable "rays". The Curies had already named "polonium"; "radium" completed the pair of radioactive elements they had extracted from pitchblende (a uranium ore).

In 1898, following the work of Henri Becquerel (1852-1903) on uranium, Marie Curie (1867-1934) discovered that pitchblende (a uranium ore) was much more radioactive than pure uranium. She deduced, with her husband Pierre, the presence of unknown, more radioactive elements. After months of titanic and physically grueling work in a rudimentary shed, they managed to separate two new elements: first polonium (July 1898), then radium (December 1898). They announced it to the Academy of Sciences on December 26, 1898. The definitive proof and isolation of radium in the form of pure chloride (RaCl₂) would not come until 1902, after the treatment of several tons of ore.

Pure metallic radium was first isolated in 1910 by Marie Curie in collaboration with André-Louis Debierne (1874-1949), by electrolysis of molten radium chloride on a mercury cathode, followed by distillation of the mercury. This success consolidated Marie Curie's international fame, who received a second Nobel Prize (this time in Chemistry) in 1911, becoming the first person to win two Nobels in different disciplines.

The extraordinary properties of radium—its intense radioactivity, spontaneous luminescence (due to the excitation of air or impurities), and decay heat—made it a true scientific and commercial celebrity. It was attributed almost miraculous virtues, leading to a craze:

This period illustrates the gap between fascination with a new technology and understanding of its dangers.

Radium does not exist in its native state. It is present in minute quantities (about 1 part per 10¹¹) in uranium ores, mainly pitchblende (UO₂) and carnotite (K₂(UO₂)₂(VO₄)₂·3H₂O). Historically, the richest mines were in Joachimsthal (now the Czech Republic) and the Belgian Congo. Extraction was extremely difficult and costly: hundreds of tons of ore had to be processed to obtain one gram of radium, making it the most expensive substance in the world (up to $120,000 per gram in the 1910s, equivalent to several million today).

Today, radium is no longer intentionally produced. The little that is used in medicine comes from historical stocks or is produced as a byproduct of nuclear waste treatment. Demand has almost disappeared.

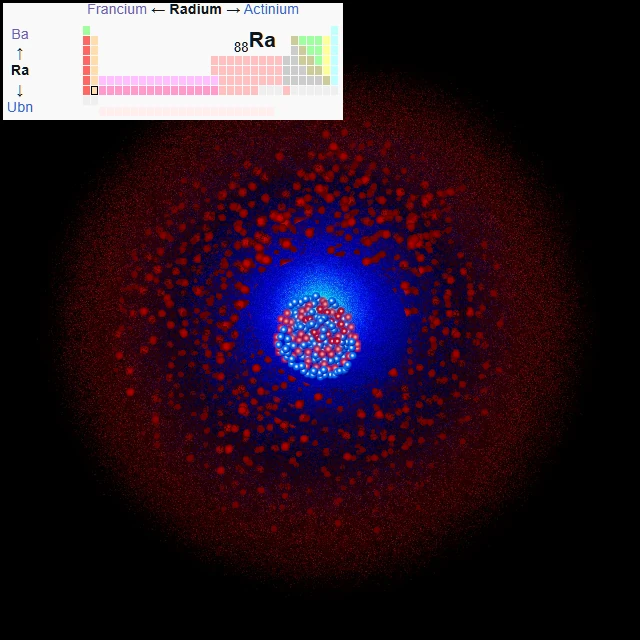

Radium (symbol Ra, atomic number 88) is an element of group 2, the alkaline earth metals. It is the heaviest and most radioactive member of this family, which includes beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, and barium. Its atom has 88 protons and, depending on the isotope, 135 to 150 neutrons. The most stable isotope, \(^{226}\mathrm{Ra}\), has 138 neutrons. Its electronic configuration is [Rn] 7s², with two valence electrons in the 7s shell.

Radium is a silvery-white alkaline earth metal that quickly blackens in air due to oxidation and nitridation. Its properties are largely extrapolated from those of barium, but complicated by its intense radioactivity.

In solid form, it crystallizes in a body-centered cubic structure.

Estimated melting point: ~973 K (~700 °C).

Estimated boiling point: ~2010 K (~1737 °C).

Chemically, radium closely resembles barium, but is even more reactive. It is a highly electropositive metal.

The chemistry of radium is difficult to study due to its radioactivity and the formation of decay products that contaminate solutions.

Atomic number: 88.

Group: 2 (Alkaline earth metals).

Electronic configuration: [Rn] 7s².

Oxidation state: +2 (exclusive).

Most stable isotope: \(^{226}\mathrm{Ra}\) (T½ = 1600 years).

Appearance: Silvery-white metal that blackens in air.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Parent chain | Half-life / Decay mode | Remarks / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radium-223 — \(^{223}\mathrm{Ra}\) | 88 | 135 | 223.018502 u | Uranium-235 (4n+3) | 11.43 days (α) | Used in medicine under the trade name Xofigo® for the treatment of painful bone metastases from prostate cancer (targeted alpha therapy). |

| Radium-224 — \(^{224}\mathrm{Ra}\) | 88 | 136 | 224.020212 u | Thorium-232 (4n) | 3.66 days (α) | Historically used in medicine. Today studied for alpha therapy. |

| Radium-226 — \(^{226}\mathrm{Ra}\) | 88 | 138 | 226.025410 u | Uranium-238 (4n+2) | 1600 years (α) | The historical and most important isotope. Discovered by the Curies. Used for decades in curietherapy and luminous paints. Source of radon-222. |

| Radium-228 — \(^{228}\mathrm{Ra}\) | 88 | 140 | 228.031070 u | Thorium-232 (4n) | 5.75 years (β⁻) | Mesothorium I. Historically used separately in luminous paints. Product of thorium-228. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Radium has 88 electrons distributed over seven electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Rn] 7s² is simple: it consists of the configuration of radon (a noble gas) plus two additional electrons in the 7s shell. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(8) Q(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁶ 7s².

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 8 electrons (6s² 6p⁶).

Q shell (n=7): 2 electrons (7s²).

Radium has two valence electrons (7s²). Like other alkaline earth metals, it easily loses these two electrons to form the Ra²⁺ ion, thus achieving the stable configuration of the noble gas radon. This high electropositivity explains its great reactivity with water and acids.

In the 1910s-20s, the U.S. Radium Corporation employed hundreds of young women to hand-paint watch dials with radium paint. To obtain a fine point, the workers were encouraged to sharpen their brushes with their lips ("lip-pointing"), thus ingesting small amounts of radium daily. In addition, they worked in dusty workshops and sometimes smeared their hair and nails with fluorescent paint for fun.

As early as the 1920s, the workers began to develop horrible pathologies: severe anemia, jaw necrosis ("radium jaw") (the jawbones literally disintegrated), spontaneous fractures, bone sarcomas, and various cancers. Doctors were initially perplexed, but the link with radium was established by Dr. Harrison Martland (1883-1954). Once ingested, radium behaved like calcium and became fixed in the bones, irradiating the bone marrow and surrounding tissues from within for decades.

Five workers, the "Radium Girls" (including Grace Fryer, Katherine Schaub), filed a landmark lawsuit against their employer in 1927. Despite the company's delaying tactics and the deteriorating health of the plaintiffs, they won their case in 1928. This trial:

The toxicity of radium is purely radiological (unlike lead or mercury, which have chemical toxicity). Once incorporated (mainly by ingestion, rarely by inhalation of dust), the Ra²⁺ ion follows the metabolism of calcium:

Long-term epidemiological studies of radium workers, patients treated with radium, and watchmakers have provided fundamental data on the effects of internal alpha radiation.

Today, radium is handled with drastic precautions:

Former industrial uses of radium have left a legacy of contaminated sites (former luminous paint factories, watchmaking workshops, waste dumps). The long half-life of Ra-226 (1600 years) means that this contamination will persist for millennia.

Collectors and museums must be aware of the risk. Objects must be stored in ventilated display cases, handled with gloves, and never opened or repaired without expertise. Flaking paint is particularly dangerous.

The era of radium as a miracle material is over. Its future lies in two very distinct areas:

Radium will remain in history as the element that opened the age of radioactivity, with its share of scientific genius, naive enthusiasm, and human suffering that ultimately led to strict regulation and acute awareness of radiological risks.