Chromium was discovered in 1797 by the French chemist Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1763–1829) while analyzing a vivid red mineral from Siberia, crocoite (lead chromate, PbCrO₄). Intrigued by the varied colors of the compounds he obtained, Vauquelin isolated a new metallic element, which he named chromium, from the Greek chroma, meaning "color," in reference to the brilliant hues of its compounds (green, yellow, orange, red). In the same year, Vauquelin also discovered beryllium, making 1797 a remarkable year in the history of chemistry. Pure metallic chromium was only isolated later, as its production requires complex reduction techniques due to its strong affinity for oxygen.

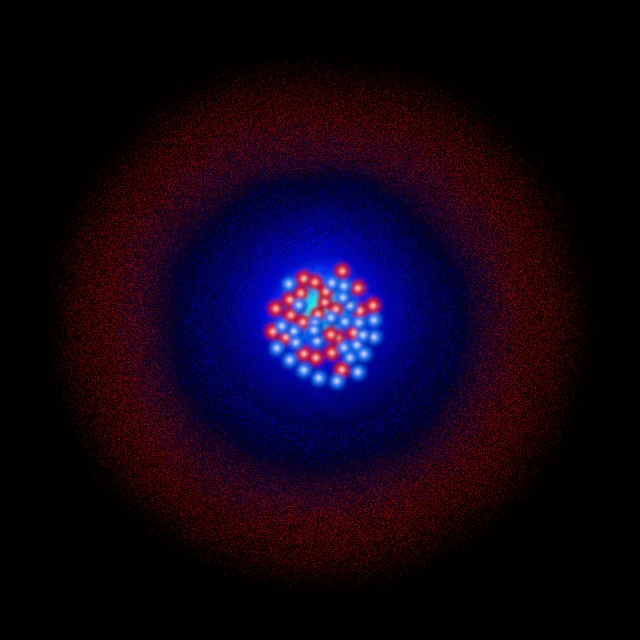

Chromium (symbol Cr, atomic number 24) is a transition metal in group 6 of the periodic table. Its atom has 24 protons, usually 28 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{52}\mathrm{Cr}\)) and 24 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹ (Ar = shorthand for the first 18 electrons of chromium).

At room temperature, chromium is a solid, silvery-white metal with a characteristic metallic luster. It is relatively dense (density ≈ 7.19 g/cm³) and extremely hard, ranking among the hardest metals. It has excellent corrosion resistance due to the spontaneous formation of a thin chromium oxide layer (Cr₂O₃), which makes it inert in air and water. Melting point of chromium (liquid state): 2,180 K (1,907 °C). Boiling point of chromium (gaseous state): 2,944 K (2,671 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic Mass (u) | Natural Abundance | Half-Life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromium-50 — \(\,^{50}\mathrm{Cr}\,\) | 24 | 26 | 49.946044 u | ≈ 4.345 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope of natural chromium. |

| Chromium-52 — \(\,^{52}\mathrm{Cr}\,\) | 24 | 28 | 51.940507 u | ≈ 83.789 % | Stable | Dominant isotope of chromium; most abundant in nature. |

| Chromium-53 — \(\,^{53}\mathrm{Cr}\,\) | 24 | 29 | 52.940649 u | ≈ 9.501 % | Stable | Has a nuclear magnetic moment; used in NMR and as an isotopic tracer. |

| Chromium-54 — \(\,^{54}\mathrm{Cr}\,\) | 24 | 30 | 53.938880 u | ≈ 2.365 % | Stable | Heaviest stable isotope of natural chromium. |

| Chromium-51 — \(\,^{51}\mathrm{Cr}\,\) | 24 | 27 | 50.944767 u | Synthetic | ≈ 27.7 days | Radioactive, electron capture to \(\,^{51}\mathrm{V}\). Used in nuclear medicine to label red blood cells. |

| Chromium-48 — \(\,^{48}\mathrm{Cr}\,\) | 24 | 24 | 47.954032 u | Synthetic | ≈ 21.6 hours | Radioactive, β⁺ decay. Produced in high-energy particle collisions. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Chromium has 24 electrons distributed across four electron shells. Its electronic configuration is remarkable: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁵ 4s¹, or simplified: [Ar] 3d⁵ 4s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(13) N(1). The unusual 3d⁵ 4s¹ configuration (instead of 3d⁴ 4s²) is due to the particular stability of a half-filled d subshell.

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 13 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁵. The 3s and 3p orbitals are complete, while the five 3d orbitals each contain one unpaired electron, creating a particularly stable half-filled configuration.

N Shell (n=4): contains only 1 electron in the 4s subshell. This unusual arrangement (only one 4s electron instead of two) results from an energetically favorable transfer to the 3d subshell.

The 6 electrons in the outer shells (3d⁵ 4s¹) are the valence electrons of chromium. This configuration explains its varied chemical properties:

By losing 1 4s electron, chromium can form the Cr⁺ ion (rare).

By losing the 4s electron and 1 3d electron, it forms the Cr²⁺ ion (oxidation state +2).

The +3 oxidation state (Cr³⁺) is very common and stable, forming many colored compounds.

The +6 oxidation state (Cr⁶⁺) exists in chromates (CrO₄²⁻) and dichromates (Cr₂O₇²⁻), which are powerful oxidizing agents.

Chromium's unique electronic configuration, with its half-filled 3d subshell, gives it exceptional magnetic stability. The five unpaired electrons make chromium a paramagnetic metal. This structure also explains the wide variety of colors in its compounds: the emerald green of Cr³⁺, the bright orange of dichromates, and the yellow of chromates.

Chromium exhibits paradoxical chemical reactivity. At room temperature, it is remarkably inert due to the Cr₂O₃ oxide layer that spontaneously forms on its surface, protecting it from corrosion. This passivation explains its use in protecting other metals. However, at high temperatures, chromium reacts vigorously with oxygen, halogens, sulfur, and nitrogen. Chromium can exist in several oxidation states, mainly +2, +3, and +6. Chromium(III) compounds are generally green and stable, while chromium(VI) compounds are yellow to red-orange and highly oxidizing. Chromium resists most dilute acids due to its passive layer but can be attacked by hot, concentrated hydrochloric acid. Chromium(VI) compounds are toxic and require careful handling.

Chromium is primarily synthesized in massive stars during the explosive silicon burning phase preceding type II supernovae. It also forms through slow neutron capture in the late stages of low- to intermediate-mass stars (about 0.6 to 10 solar masses). The relative abundance of chromium isotopes in primitive meteorites provides valuable clues about the physical conditions in the protoplanetary disk and the early stages of solar system formation.

Chromium plays an important role in stellar spectroscopy. The absorption lines of neutral chromium (Cr I) and ionized chromium (Cr II) are used to determine the chemical composition, effective temperature, and metallicity of stars. Studying the chromium/iron ratio in ancient stars in our galaxy helps understand the chemical evolution of the Milky Way and the relative contributions of different types of supernovae to the enrichment of the interstellar medium. Certain chemically peculiar stars show chromium overabundances due to radiative diffusion processes in their atmospheres.

N.B.:

Chromium is relatively abundant in the Earth's crust, ranking 21st with about 0.014% by mass. It is mainly found as chromite (FeCr₂O₄), the only economically viable chromium ore. The main deposits are in South Africa, Kazakhstan, and India. Extracting metallic chromium requires ore reduction, usually through aluminothermy or electrolysis. Although less complex than titanium extraction, producing high-purity chromium for specialized applications remains technically demanding. Global demand for chromium continues to grow, driven mainly by the stainless steel industry, which consumes about 85% of global production.