Actinium is not produced in significant quantities by classical stellar processes. It is a heavy and radioactive chemical element that forms mainly during extreme astrophysical processes such as neutron star mergers (r-process) or supernova explosions. In these environments, light atomic nuclei rapidly capture a succession of neutrons to form heavy and unstable isotopes that then decay into elements of the actinide series, including actinium. Unlike aluminum-26, which serves as a cosmic "chronometer," actinium isotopes have half-lives that are too short (the most stable is 227Ac with 21.772 years) to be detected in interstellar space. However, their existence in the solar system is attested by their trace presence in uranium ores, where they are continuously produced by the decay chains of uranium and thorium.

Actinium was discovered in 1899 by the French chemist André-Louis Debierne (1874-1949). He isolated it from pitchblende (a uranium ore), after noticing that the radioactivity of certain residues was stronger than that of uranium itself. He named the new element "actinium" (from the Greek aktinos, ray) because of its luminescence and radioactive properties. In 1902, Friedrich Oskar Giesel (1852-1927) independently discovered the same element, which he initially called "emanium." However, priority was given to Debierne. It took several decades before macroscopic and pure samples of metallic actinium were produced, due to its extreme rarity (it represents about 0.2 ppm in pitchblende) and the difficulty of separating it from other elements in the ore, particularly lanthanum, with which it shares many chemical properties. In 1947, researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory finally succeeded in isolating and characterizing pure metallic actinium.

N.B.:

Actinium was long the "lost element." Its early discovery in 1899 was quickly overshadowed by that of radium (1898), which captivated the attention of the public and scientists due to its intense radioactivity and promising medical applications. Actinium, rarer and less intense, remained in the shadows for decades. It was only much later, with the advent of nuclear physics and the development of radiochemistry, that its importance as the "founding father" of the actinide series and its unique properties were fully recognized. Its isotope 227Ac, in particular, is a major source of alpha particles in radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) used for deep space missions.

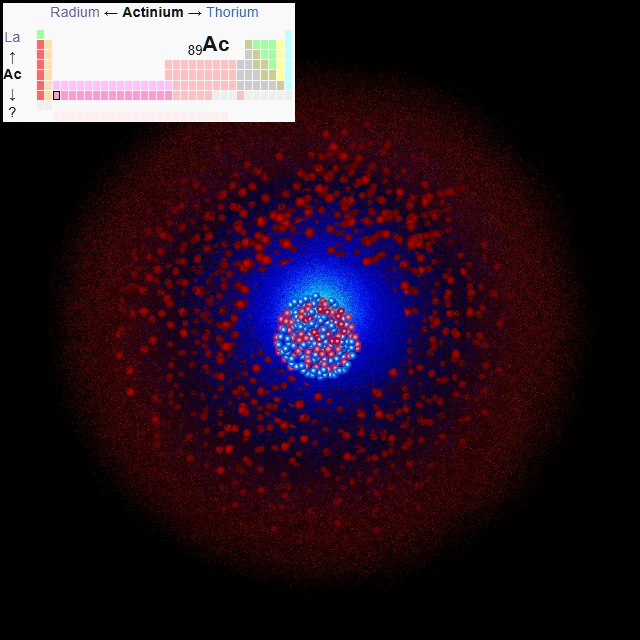

Actinium (symbol Ac, atomic number 89) is the first element of the actinide series in the periodic table. Its atom has 89 protons, 89 electrons, and a variable number of neutrons depending on the isotope. It shares chemical similarities with lanthanum, located just above in group 3, to the point of often being considered its radioactive analog. In its pure metallic state, actinium is a silvery and soft solid, with a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure. Its density is about 10.07 g/cm³. It exhibits significant radioactivity: all its isotopes are unstable. It spontaneously forms an oxide layer (Ac₂O₃) in air and readily reacts with halogens.

Melting point: ≈ 1323 K (1050 °C).

Boiling point: ≈ 3473 K (3200 °C, estimated).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic Mass (u) | Natural Abundance | Half-Life / Stability | Main Decay Mode / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinium-227 — \(\,^{227}\mathrm{Ac}\,\) | 89 | 138 | 227.027752 u | Trace (in uranium) | 21.772 years | β– (98.62%) and α (1.38%). Most abundant natural isotope. Major source of 227Th and 223Ra for medical applications. |

| Actinium-228 — \(\,^{228}\mathrm{Ac}\,\) | 89 | 139 | 228.031021 u | Trace (in thorium) | 6.15 hours | β– at 100%. Formed in the decay chain of thorium-232. Used as a tracer in research. |

| Actinium-225 — \(\,^{225}\mathrm{Ac}\,\) | 89 | 136 | 225.023230 u | Not natural (synthetic) | 10.0 days | α at 100% (four successive α decays). Produced from radium-229. Key element in targeted alpha therapy (TAT) against cancer. |

| Actinium-226 — \(\,^{226}\mathrm{Ac}\,\) | 89 | 137 | 226.026098 u | Not natural | 29.37 hours | β– (83%) and ε (17%). Intermediate isotope produced in the laboratory for nuclear physics studies. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Actinium has 89 electrons. Its ground state electronic configuration is [Rn] 6d1 7s2. This means it has the electronic core of radon (Rn, Z=86) and places its last three electrons in the 6d and 7s orbitals. This configuration can also be written in a simplified manner: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(9) Q(2). Its single 6d electron explains its chemical similarities with lanthanum ([Xe] 5d1 6s2).

Actinium has three valence electrons (configuration 6d1 7s2). Like other group 3 elements (scandium, yttrium, lanthanum), it exhibits almost exclusively the +3 oxidation state (Ac3+ ion). In this state, it loses its three valence electrons to achieve a stable noble gas electronic configuration ([Rn]). There are practically no actinium compounds in the +2 or +1 oxidation states, due to the high stability of the trivalent ion.

In aqueous solution, the Ac3+ ion is the only stable state. It forms hydrated complexes, and its salts (such as AcCl3 or Ac(NO3)3) are generally water-soluble, except with certain anions (fluorides, phosphates, oxalates). Its chemistry is extremely similar to that of lanthanum (La3+), making their chemical separation very difficult. This is explained by their almost identical ionic radius and the same charge. Separation therefore relies almost exclusively on subtle differences in the stability constants of complexes or on radiochemical separation methods exploiting the decay of its isotopes.

The intense radioactivity of actinium has major practical consequences. In solid compounds, the alpha particles emitted by decay cause self-irradiation that gradually damages the crystal lattice, changes the color of salts (from white to brown or black), and can even release gases (helium from alpha particles). In solution, radiolysis (breaking of water molecules by radiation) generates radical species and can alter the pH. These effects must be carefully considered for the storage and handling of this element.

Metallic actinium is a powerful reducing agent. It oxidizes rapidly in air to form actinium(III) oxide, Ac2O3. It reacts with non-oxidizing mineral acids (such as HCl) by releasing hydrogen and forming the corresponding Ac(III) salts. Its reactivity is comparable to that of alkaline earth metals, but its handling is complicated by its radioactivity. It forms halides (AcX3), oxides, hydroxides, and salts with most common anions. Its chemistry is entirely dominated by the +3 state, and it does not show the variety of oxidation states observed in heavier actinides (such as uranium or plutonium).

Actinium is one of the rarest natural elements. It is estimated that there are only a few grams of natural actinium-227 in the Earth's crust at any given time, mainly in uranium ores such as pitchblende. Its industrial production is therefore extremely limited and costly. The main source is the neutron irradiation of radium-226 in a nuclear reactor, according to the reaction: 226Ra(n,γ)227Ra → (β–, 42.2 min) → 227Ac. The subsequent chemical separation of actinium from radium and fission products is a major challenge in radiochemistry. Actinium-225, even rarer, is mainly produced by irradiation of thorium-232 with high-energy protons in a particle accelerator, or by extraction from thorium-229 generators (itself derived from uranium-233). Its cost can reach several hundred thousand dollars per milligram, making it one of the most valuable materials in the world.

Actinium is a highly radioactive and toxic element. Its handling requires suitable facilities (sealed glove boxes under inert atmosphere, lead or concrete shielded cells) and specialized training in radiation protection. The main hazards come from: 1. External irradiation: Alpha, beta, and gamma emissions from its isotopes and their descendants. 2. Internal contamination: If inhaled or ingested, it permanently fixes in the bones (like calcium and strontium), irradiating neighboring tissues and potentially inducing cancers or bone marrow damage. Its annual limit on intake (ALI) is extremely low. It is stored in solid inert form, in sealed and shielded containers, often protected from air to prevent dust formation.