Erbium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in low- to medium-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch), with a significant contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae. Nucleosynthesis models estimate that about 70-80% of solar erbium comes from the s-process, and 20-30% from the r-process. As a lanthanide with an even number of protons (Er, Z = 68), it is more abundant than its odd neighbors (holmium-67 and thulium-69) according to the Oddo-Harkins rule.

The cosmic abundance of erbium is about 2.5×10⁻¹² times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about 5 times more abundant than holmium and similar in abundance to dysprosium. Among the heavy rare earths, it is relatively more abundant due to its even atomic number and the particular stability of some of its isotopes. This relative abundance has facilitated its large-scale technological use.

Erbium is considered one of the best tracers of the s-process among heavy rare earths due to its strong preference for this nucleosynthesis process. The erbium/europium (Er/Eu) ratio is particularly useful for studying the history of AGB stars' contribution to the chemical enrichment of the Galaxy. Stars enriched in s-process elements show high Er/Eu ratios, while metal-poor stars dominated by the r-process exhibit lower ratios.

Erbium has been detected in many stars thanks to its relatively accessible spectral lines, particularly those of the Er II ion. These detections have made it possible to map the abundance of erbium in different stellar populations of the Milky Way, providing important constraints on models of galactic nucleosynthesis. The study of erbium in extremely metal-poor stars helps to understand the production of the first heavy elements in the Universe.

Erbium takes its name from the Swedish village of Ytterby, located on the island of Resarö near Stockholm, famous for its quarry that provided minerals containing several rare earths. Ytterby gave its name to four elements: yttrium (Y), terbium (Tb), erbium (Er), and ytterbium (Yb). The name "erbium" was formed by analogy with the other elements discovered in the ores from this locality.

Erbium was discovered in 1843 by the Swedish chemist Carl Gustaf Mosander (1797-1858), who worked at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Mosander was studying an yttria mineral (yttrium oxide) from Ytterby. After numerous fractional crystallizations, he succeeded in separating this oxide into three distinct compounds, which he named yttria (white), erbia (pink), and terbia (yellow). The "erbia" he isolated contained mainly erbium oxide, although the complete purification of the element took several decades.

As with terbium, there was confusion for several years regarding the names "erbia" and "terbia". Some chemists reversed the designations, assigning the name "erbia" to what is now called terbia (terbium oxide) and vice versa. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the nomenclature was definitively established according to Mosander's original discovery. The isolation of relatively pure erbium metal was first achieved in 1905 by the French chemists Georges Urbain and Charles James.

Erbium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 3.5 ppm (parts per million), making it more abundant than holmium but less so than dysprosium. Among the heavy rare earths, it is relatively abundant. The main ores containing erbium are bastnaesite ((Ce,La,Nd,Er)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Er,Th)PO₄), where it typically represents 0.1 to 0.5% of the total rare earth content, and xenotime (YPO₄) where it can be more concentrated (up to 4-5%).

Global production of erbium oxide (Er₂O₃) is about 50 to 100 tons per year, which is significant but remains low compared to light rare earths. Due to its critical importance for telecommunications, erbium is a strategic rare earth, with typical prices ranging from 300 to 700 dollars per kilogram of oxide. China dominates production with more than 85% of the world total, followed by the United States, Australia, and Malaysia.

Erbium metal is mainly produced by metallothermic reduction of erbium fluoride (ErF₃) with metallic calcium in an inert argon atmosphere. Global annual production of erbium metal is about 10 to 20 tons. Recycling erbium from optical fibers and other electronic waste is technically possible but economically difficult due to low concentrations, although research in this area is active.

Erbium (symbol Er, atomic number 68) is the twelfth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the f-block rare earths of the periodic table. Its atom has 68 protons, 98 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{166}\mathrm{Er}\)) and 68 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹² 6s². This configuration gives erbium exceptional optical properties.

Erbium is a silvery, malleable, and relatively soft metal. It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature. Erbium is paramagnetic at room temperature and becomes antiferromagnetic below 85 K (-188 °C), then exhibits a helical magnetic structure below 52 K (-221 °C). At very low temperatures (below 20 K), it becomes ferromagnetic. These complex magnetic properties are studied in solid-state physics but are less technologically exploited than its optical properties.

Erbium melts at 1529 °C (1802 K) and boils at 2868 °C (3141 K). Like most lanthanides, it has high melting and boiling points. Erbium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 1495 °C where its crystal structure changes from hexagonal close-packed (HCP) to body-centered cubic (BCC). Its electrical conductivity is poor, about 25 times lower than that of copper.

Erbium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, but slowly oxidizes to form a pink Er₂O₃ oxide. It oxidizes more rapidly when heated and burns to form the oxide: 4Er + 3O₂ → 2Er₂O₃. Erbium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form erbium(III) hydroxide Er(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids. The metal must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere.

Melting point of erbium: 1802 K (1529 °C).

Boiling point of erbium: 3141 K (2868 °C).

Néel temperature (antiferromagnetic transition): 85 K (-188 °C).

Transition temperature to helical order: 52 K (-221 °C).

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erbium-162 — \(\,^{162}\mathrm{Er}\,\) | 68 | 94 | 161.928778 u | ≈ 0.14 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope, very rare in nature. |

| Erbium-164 — \(\,^{164}\mathrm{Er}\,\) | 68 | 96 | 163.929200 u | ≈ 1.61 % | Stable | Stable isotope present in small quantities. |

| Erbium-166 — \(\,^{166}\mathrm{Er}\,\) | 68 | 98 | 165.930293 u | ≈ 33.61 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope in nature (about one third of the total). |

| Erbium-167 — \(\,^{167}\mathrm{Er}\,\) | 68 | 99 | 166.932048 u | ≈ 22.93 % | Stable | Major stable isotope, second in abundance. |

| Erbium-168 — \(\,^{168}\mathrm{Er}\,\) | 68 | 100 | 167.932370 u | ≈ 26.78 % | Stable | Important stable isotope, similar in abundance to erbium-167. |

| Erbium-170 — \(\,^{170}\mathrm{Er}\,\) | 68 | 102 | 169.935464 u | ≈ 14.93 % | Stable | Heaviest stable isotope, representing about 15% of the natural mixture. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

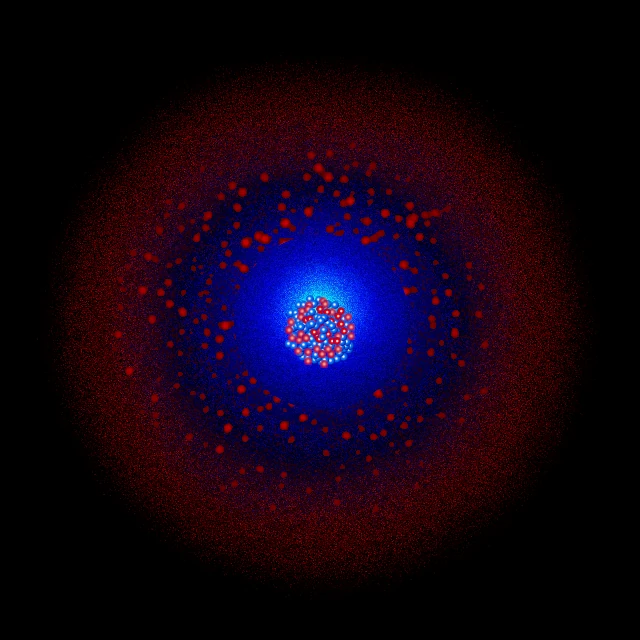

Erbium has 68 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹² 6s² has twelve electrons in the 4f subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(30) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹² 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 30 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹² 5d⁰. The twelve 4f electrons give erbium its exceptional optical properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of erbium.

Erbium effectively has 14 valence electrons: twelve 4f¹² electrons and two 6s² electrons. Erbium exclusively exhibits the +3 oxidation state in its stable compounds. In this state, erbium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Er³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹¹. This ion has eleven electrons in the 4f subshell and exhibits electronic transitions that are the basis of its major optical applications.

Unlike some lanthanides such as europium or ytterbium, erbium does not form stable +2 or +4 oxidation states under normal conditions. A few erbium(II) compounds have been synthesized under extreme conditions but are very unstable. The +3 state is therefore the only chemically and technologically significant one.

The chemistry of erbium is dominated by the +3 state. The Er³⁺ ion has an ionic radius of 103.0 pm (for coordination number 8) and forms complexes that are generally pale pink in aqueous solution, a characteristic color of erbium salts. Its exceptional optical properties, particularly its transitions in the near infrared, are exploited in optical fibers and lasers.

Erbium metal is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin protective layer of Er₂O₃ oxide. At high temperatures (above 200 °C), it oxidizes rapidly and burns to form the oxide: 4Er + 3O₂ → 2Er₂O₃. Erbium(III) oxide is a characteristic pink solid with a cubic C-type rare earth structure (C-type sesquioxide). In fine powder form, erbium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Erbium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form erbium(III) hydroxide Er(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Er + 6H₂O → 2Er(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a pale pink gelatinous solid that is slightly soluble. As with other lanthanides, the reaction is not violent but is observable over time.

Erbium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides: 2Er + 3F₂ → 2ErF₃ (pink fluoride); 2Er + 3Cl₂ → 2ErCl₃ (violet chloride). Erbium dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) with the release of hydrogen and the formation of the corresponding Er³⁺ salts: 2Er + 6HCl → 2ErCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Erbium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperatures (300-400 °C) to form ErH₂ hydride, then ErH₃ at higher temperatures. With sulfur, it forms Er₂S₃ sulfide. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperatures (>1000 °C) to form ErN nitride, and with carbon to form ErC₂ carbide. Erbium also forms coordination complexes with organic ligands, although this chemistry is less developed than its optical applications.

The most important property of erbium is its exceptional optical behavior. The Er³⁺ ion has electronic transitions that allow it to emit light in the near infrared, particularly at the wavelength of 1.55 micrometers (1550 nm). This wavelength is crucial because it corresponds to the minimum transmission window of silica optical fibers, where attenuation is lowest (about 0.2 dB/km). This fortuitous coincidence makes erbium the ideal element for amplifying optical signals in global telecommunications networks.

The invention of erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFA) in the 1980s revolutionized global communications. Before EDFAs, optical signals in fibers had to be electronically regenerated every 50-100 km (detection, conversion to electrical signal, electronic amplification, then reconversion to optical signal). EDFAs allow direct amplification of the optical signal without electronic conversion, significantly reducing costs and complexity while increasing network capacity.

In an EDFA, a silica optical fiber is doped with Er³⁺ ions (typically a few hundred parts per million). This fiber is optically "pumped" by laser diodes at 980 nm or 1480 nm. The Er³⁺ ions absorb this pump light and are excited to a higher energy level. When communication optical signals at 1550 nm pass through the fiber, they stimulate the excited ions to emit additional photons at the same wavelength, thus amplifying the signal. This process is stimulated emission, the same principle as in a laser.

- Wavelength: Optimal amplification around 1550 nm, corresponding to the minimum transmission window of fibers.

- Bandwidth: About 30-40 nm, allowing simultaneous amplification of many channels (WDM: Wavelength Division Multiplexing).

- Gain: Typically 20-30 dB (amplification factor of 100 to 1000).

- Noise figure: Low (4-5 dB), essential for long-distance transmissions.

- Output power: Up to several watts for power amplifiers.

- Length of doped fiber: Generally 10-30 meters.

EDFAs have enabled the development of transoceanic submarine fiber optic networks, long-distance terrestrial networks, and have multiplied network capacity through wavelength division multiplexing (WDM). Without erbium, global high-speed internet, international fiber telephony, and many modern cloud services would be impossible or extremely expensive. A typical EDFA contains a few milligrams to a few grams of erbium.

The Er:YAG laser emits at a wavelength of 2.94 µm, which is very strongly absorbed by water (about 10,000 times more than at 1.06 µm, the wavelength of the Nd:YAG laser). This property makes it ideal for medical and dental applications where precise ablation of hydrated tissues is required with minimal thermal damage to surrounding tissues.

Er:glass lasers typically emit around 1.54 µm or 1.55 µm. They are used for:

These lasers use an erbium-doped optical fiber as the gain medium. They are compact, efficient, and produce excellent beam quality. Applications:

Erbium has a moderate thermal neutron absorption cross section (about 166 barns for the Er-167 isotope, the most effective). This property allows erbium to be used in nuclear reactor control rods, although its use is less common than that of other materials such as boron, cadmium, or gadolinium. Erbium is sometimes used in experimental nuclear fuels as a burnable poison to control reactivity.

Erbium oxide (Er₂O₃) is being studied as a protective coating for nuclear reactor components due to its stability under irradiation and good thermal conductivity. These coatings could improve the safety and lifespan of nuclear fuels.

Er³⁺ ions give glass and ceramics a characteristic pink color. This property is exploited for:

Some erbium-doped materials (often in combination with ytterbium) can convert two low-energy infrared photons into a higher-energy visible photon (upconversion phenomenon). Applications:

Research is underway to use erbium in solar cells to increase their efficiency. The idea is to convert high-energy photons (UV, blue) into several lower-energy photons (in the optimal absorption range of silicon) via a quantum cutting process.

Erbium and its compounds have low chemical toxicity, comparable to other lanthanides. Soluble salts can cause skin, eye, and respiratory irritation. No severe acute toxicity or carcinogenic effects have been demonstrated. The LD50 (median lethal dose) of erbium salts in animals is similar to that of other lanthanides (typically >500 mg/kg). Erbium has no known biological role.

Like other lanthanides, erbium preferentially accumulates in the liver and bones in case of exposure, with very slow elimination. General population exposure is extremely low, mainly limited to workers in the relevant industries.

The environmental impacts are related to rare earth mining in general. The extraction of one kilogram of erbium requires the processing of several tons of ore, generating significant waste and environmental impacts. However, the total amount of erbium used worldwide is relatively small (a few tens of tons per year) compared to other metals.

Recycling erbium from used optical fibers is technically possible but economically difficult due to the low concentration of erbium in fibers (typically a few hundred ppm) and the difficulty of separating erbium from silica. However, with the increase in optical fiber waste volumes and advances in recycling techniques, this route could become more interesting in the future.

Erbium is classified as a critical raw material by several countries and regions (United States, European Union) due to its importance for critical infrastructure (telecommunications) and the geographical concentration of its production (China). Efforts are underway to diversify supply, improve use efficiency (reduce the amount of erbium needed per EDFA), and develop alternative technologies.

Occupational exposure occurs in rare earth production plants, optical fiber manufacturing, laser crystal production, and telecommunications facilities. Standard precautions for metal dusts apply. In medical applications (lasers), standard precautions for class 4 lasers apply.