Silver is one of the seven metals known since antiquity, along with gold, copper, lead, tin, iron, and mercury. Its use dates back at least 5000 years before our era in Anatolia (present-day Turkey), where objects made of native hammered silver were discovered. Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Indus Valley civilizations used silver for jewelry, ritual objects, and as currency.

The name silver derives from the Old English seolfor, of Germanic origin. The chemical symbol Ag comes directly from the Latin argentum, itself probably derived from an Indo-European root meaning bright or white. This linguistic duality (argent/silver) is unique among common chemical elements.

The first methods for extracting silver from silver-bearing lead ores were developed around 3000 BCE in Anatolia. The cupellation process, described since antiquity, allowed the separation of silver from lead by oxidizing the lead at high temperatures. The mines of Laurion in Greece, exploited from the 6th century BCE, provided the silver that financed Athens' maritime power and the construction of the Parthenon.

The discovery of the New World in 1492 revolutionized the global silver economy. Spanish mines in Potosí (present-day Bolivia) and Zacatecas (Mexico), exploited from the 1540s using the patio process (mercury amalgamation), produced colossal amounts of silver that flooded Europe and Asia for three centuries. Between 1500 and 1800, the Americas provided about 85% of the world's silver production.

Silver (symbol Ag, atomic number 47) is a transition metal in group 11 of the periodic table, along with copper and gold. Its atom has 47 protons, usually 60 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{107}\mathrm{Ag}\)) and 47 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s¹.

Silver is a white, shiny metal with the highest metallic luster of all elements. It has a density of 10.49 g/cm³, making it relatively heavy but much less dense than gold (19.3 g/cm³) or platinum (21.5 g/cm³). Silver crystallizes in a face-centered cubic (fcc) structure. It is extremely ductile and malleable, capable of being rolled into sheets 0.00025 mm thick and drawn into very fine wires.

Silver holds several absolute records among all elements. It has the highest electrical conductivity of all metals at room temperature (63.0 × 10⁶ S/m), even surpassing copper. It also has the highest thermal conductivity (429 W/m·K at 20 °C) and the highest reflectivity in the visible and infrared spectrum (about 95-99% depending on the wavelength).

Silver melts at 962 °C (1235 K) and boils at 2162 °C (2435 K). These relatively low temperatures compared to other precious metals facilitate its processing and alloying. Pure silver is too soft for most practical applications and is generally alloyed with other metals, especially copper, to increase its hardness.

Melting point of silver: 1235 K (962 °C).

Boiling point of silver: 2435 K (2162 °C).

Silver has the highest electrical and thermal conductivity of all metals.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver-107 — \(\,^{107}\mathrm{Ag}\,\) | 47 | 60 | 106.905097 u | ≈ 51.84 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope of silver, slightly majority. Decay product of palladium-107. |

| Silver-109 — \(\,^{109}\mathrm{Ag}\,\) | 47 | 62 | 108.904752 u | ≈ 48.16 % | Stable | Second stable isotope, almost as abundant as silver-107. |

| Silver-105 — \(\,^{105}\mathrm{Ag}\,\) | 47 | 58 | 104.906528 u | Synthetic | ≈ 41.3 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Used in nuclear medicine and as an industrial tracer. |

| Silver-110m — \(\,^{110m}\mathrm{Ag}\,\) | 47 | 63 | 109.906107 u | Synthetic | ≈ 249.8 days | Radioactive (β⁻, isomeric transition). Used in dosimetry and as an environmental tracer. |

| Silver-111 — \(\,^{111}\mathrm{Ag}\,\) | 47 | 64 | 110.905291 u | Synthetic | ≈ 7.45 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Used in nuclear medicine for imaging and targeted therapy. |

N.B. :

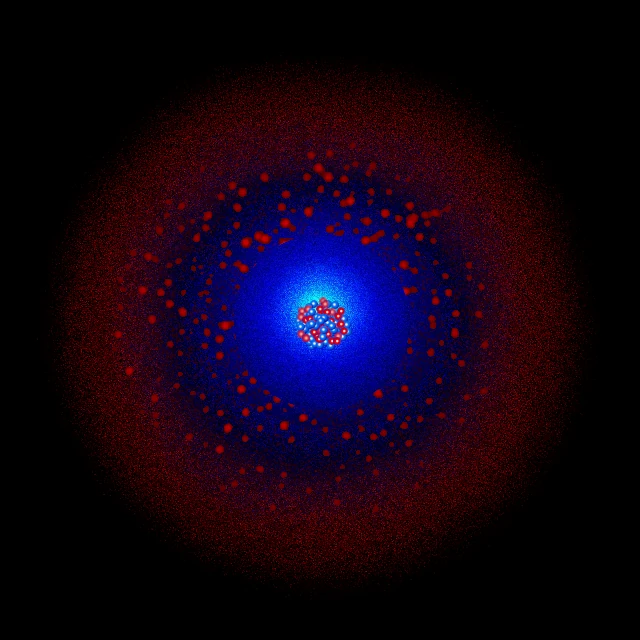

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Silver has 47 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s¹, or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(1).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O shell (n=5): contains 1 electron in the 5s subshell. This single electron is the valence electron of silver.

Silver has 1 valence electron in its 5s¹ subshell, although the 10 electrons in the 4d¹⁰ subshell can also participate in chemical bonding under certain conditions. The most common oxidation state is +1, where silver loses its 5s electron to form the Ag⁺ ion with the configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰, which is extremely stable.

The +1 state dominates the chemistry of silver and appears in most of its compounds: silver nitrate (AgNO₃), silver chloride (AgCl), silver oxide (Ag₂O), and countless coordination complexes. The +2 state exists in a few compounds such as silver(II) fluoride (AgF₂), but these compounds are unstable and highly oxidizing. The +3 state is extremely rare and only exists in a few highly stabilized complexes. Metallic silver corresponds to the oxidation state 0.

Silver is relatively unreactive, which explains its occurrence in native form in nature. It does not oxidize in air under normal conditions, but reacts slowly with traces of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) in the atmosphere to form black silver sulfide (Ag₂S), causing the characteristic tarnishing of silver objects: 4Ag + 2H₂S + O₂ → 2Ag₂S + 2H₂O.

Silver resists most dilute acids but dissolves easily in nitric acid, forming silver nitrate and releasing nitrogen dioxide: 3Ag + 4HNO₃ → 3AgNO₃ + NO + 2H₂O. It also dissolves in hot concentrated sulfuric acid and in cyanide solutions in the presence of oxygen, a reaction used for the extraction of silver from ores (cyanidation process).

Silver has remarkable antibacterial and antifungal properties, empirically known since antiquity. Ag⁺ ions released by metallic silver or its compounds interact with bacterial cell membranes, disrupt enzymatic functions, and damage DNA, thus effectively killing microorganisms. This property is exploited in antibacterial dressings, medical catheter coatings, water purifiers, and antimicrobial textiles.

Silver forms slightly soluble halides (AgCl, AgBr, AgI) that are photosensitive, darkening under the effect of light. This property was the basis of silver photography for over a century and a half, from daguerreotypes in 1839 to the digital era of the 21st century.

A major modern application of silver, which is growing rapidly, is in the photovoltaic industry. Crystalline silicon solar cells, which dominate the market with over 95% share, use silver-containing metallization pastes to collect and transport the generated electricity.

Each standard solar cell contains about 100-130 mg of silver in the form of fine lines (fingers) screen-printed on the front and contacts on the back. The exceptional electrical conductivity of silver minimizes resistive losses, thus maximizing the cell's conversion efficiency. No other metal can rival silver's performance for this critical application.

The photovoltaic industry now consumes about 3000 tons of silver per year, accounting for more than 10% of total global demand. With the massive expansion of solar energy to combat climate change, this demand could double or triple by 2030. Researchers are actively working on alternatives (plated copper, alloys, quantity reduction) to reduce dependence on silver and production costs.

Silver has served as currency for millennia, often in parity with gold in bimetallic systems. The gold/silver ratio has historically varied between 10:1 and 20:1 in different civilizations. Silver coins circulated as common currency until the mid-20th century, before being gradually demonetized and replaced by cupronickel alloys.

Today, silver retains a role as an investment and store of value. It is traded on international financial markets, mainly at the London Bullion Market and the COMEX in New York. The price of silver is much more volatile than that of gold due to its dual nature as a precious metal and industrial material. The modern gold/silver ratio generally fluctuates between 50:1 and 80:1, reflecting the relatively greater abundance of silver.

The price of silver has seen spectacular variations: around $5 per troy ounce in the 1990s-2000s, a historic peak of $50 in 1980 (Hunt brothers manipulation) and again in 2011 (post-financial crisis speculation), then stabilization around $15-$25 in the 2010s-2020s. Global silver investment reserves (bullion, coins, ETFs) represent about 2-3 billion troy ounces.

Silver is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with a significant contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. The two stable isotopes of silver (Ag-107 and Ag-109) are produced by these processes with relative contributions depending on nucleosynthetic conditions.

The cosmic abundance of silver is about 4.8×10⁻¹⁰ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This modest abundance reflects silver's position beyond the iron peak in the nuclear stability curve, where the production of heavy elements becomes progressively less efficient.

Silver-107 is the decay product of radioactive palladium-107 (half-life 6.5 million years). Excesses of silver-107 measured in some primitive meteorites demonstrate that palladium-107 was alive during the formation of the solar system. The initial ¹⁰⁷Pd/¹⁰⁸Pd ratio, deduced from silver-107 anomalies, provides chronological constraints on nucleosynthesis events preceding the formation of the solar system.

Spectral lines of neutral silver (Ag I) and ionized silver (Ag II) are observable in the spectra of certain cool stars and giant stars. The analysis of these lines allows the determination of silver abundance in stellar atmospheres and the tracing of the chemical enrichment of galaxies. Excesses of silver have been detected in some stars enriched in s-process elements, confirming the role of AGB stars in silver production.

N.B. :

Silver is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.075 ppm, about 20 times rarer than copper but 15-20 times more abundant than gold. Silver is found in native form (about 25% of production) and in more than 200 ores, mainly argentite (Ag₂S), cerargyrite (AgCl), and associated with lead (galena), copper, zinc, and gold ores.

Global silver production is about 25,000 to 27,000 tons per year. Mexico is the world's leading producer (about 22%), followed by Peru, China, Russia, Chile, Australia, and Poland. About 70% of silver is produced as a by-product of lead, zinc, copper, and gold extraction, and only 30% comes from primary silver mines.

Silver recycling is important, accounting for about 25-30% of annual supply. Silver is recovered from electronic waste, silver photographs and films (in decline), industrial catalysts, jewelry, and silverware. The high recycling rate of silver is explained by its economic value and the relative ease of recovery from concentrated sources.