Niobium was discovered in 1801 by the British chemist Charles Hatchett (1765-1847), who named it columbium in honor of America. In 1844, the German chemist Heinrich Rose (1795-1864) demonstrated that minerals containing tantalum contained a second distinct element, which he named niobium in reference to Niobe, daughter of Tantalus in Greek mythology.

A nomenclature controversy opposed European chemists (favoring the name niobium) and American chemists (preferring columbium) for over a century. It was not until 1950 that the IUPAC officially adopted the name niobium. The isolation of pure metallic niobium was achieved in 1864 by Christian Wilhelm Blomstrand.

Niobium (symbol Nb, atomic number 41) is a transition metal in group 5 of the periodic table. Its atom has 41 protons, usually 52 neutrons (for the only stable isotope \(\,^{93}\mathrm{Nb}\)) and 41 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d⁴ 5s¹.

Niobium is a shiny, gray-white metal with a slight bluish tint. It has a density of 8.57 g/cm³ and is relatively soft and ductile. It crystallizes in a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure at all temperatures. Niobium melts at 2477 °C (2750 K) and boils at 4744 °C (5017 K).

The most remarkable property of niobium is its superconductivity. It becomes superconducting below 9.2 K (-263.95 °C), the highest critical temperature of all pure metallic elements. This property makes niobium the basic material for most industrial superconducting applications.

Melting point of niobium: 2750 K (2477 °C).

Boiling point of niobium: 5017 K (4744 °C).

Superconducting critical temperature: 9.2 K (-263.95 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Niobium-93 — \(\,^{93}\mathrm{Nb}\,\) | 41 | 52 | 92.906378 u | 100 % | Stable | Only stable isotope of niobium. Niobium is a mononuclidic element. |

| Niobium-92 — \(\,^{92}\mathrm{Nb}\,\) | 41 | 51 | 91.907194 u | Synthetic | ≈ 3.47 × 10⁷ years | Radioactive (electron capture). Extinct isotope used in cosmochemistry to date the early solar system. |

| Niobium-94 — \(\,^{94}\mathrm{Nb}\,\) | 41 | 53 | 93.907283 u | Synthetic | ≈ 2.03 × 10⁴ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Produced by cosmic rays, used to date meteorite exposure. |

| Niobium-95 — \(\,^{95}\mathrm{Nb}\,\) | 41 | 54 | 94.906835 u | Synthetic | ≈ 35.0 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Important fission product. Used as a tracer in research. |

N.B.:

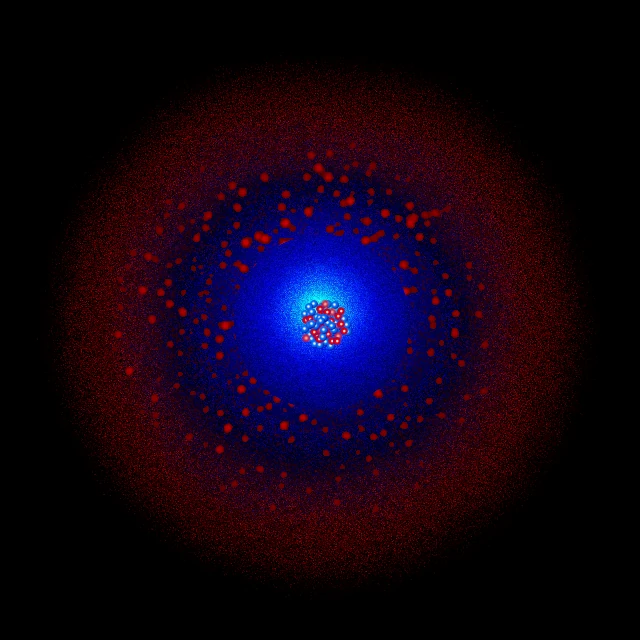

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Niobium has 41 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁴ 5s¹, or simplified: [Kr] 4d⁴ 5s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(12) O(1).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N Shell (n=4): contains 12 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁴. The four 4d electrons are valence electrons.

O Shell (n=5): contains 1 electron in the 5s subshell. This electron is also a valence electron.

Niobium has 5 valence electrons: four 4d⁴ electrons and one 5s¹ electron. The most common and stable oxidation state is +5, where niobium forms the Nb⁵⁺ ion. Niobium pentoxide (Nb₂O₅) is the most important compound. Oxidation states +4, +3, +2, and +1 exist in less stable compounds. The electronegativity of niobium (1.6 on the Pauling scale) is moderate.

At room temperature, niobium is remarkably resistant to corrosion due to a thin protective oxide layer (Nb₂O₅). It oxidizes significantly above 200 °C and can burn in pure oxygen above 400 °C: 4Nb + 5O₂ → 2Nb₂O₅.

Niobium reacts with halogens at high temperatures to form pentahalides: 2Nb + 5X₂ → 2NbX₅. It resists most acids due to its oxide layer but is attacked by hydrofluoric acid, which dissolves this protective layer. Niobium absorbs hydrogen reversibly and forms alloys with many metals, notably the superconducting Nb-Ti alloys.

Niobium is at the heart of superconductor technology. The niobium-titanium alloy (Nb-Ti, 47% Ti) is the most widely used superconducting material in the world, becoming superconducting below 10 K and supporting magnetic fields up to 15 teslas. More than 1000 tons of Nb-Ti are produced annually for medical MRI, NMR spectrometers, and particle accelerators.

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN uses about 1200 tons of niobium in its superconducting magnets. The 1232 dipole magnets, cooled to 1.9 K by superfluid helium, generate fields of 8.3 teslas to guide the proton beams. The RF resonant cavities of the LHC, made of ultra-pure niobium and cooled to 2 K, accelerate particles with remarkable energy efficiency.

For more intense magnetic fields (up to 25-30 teslas), the Nb₃Sn compound is used despite its brittleness and manufacturing complexity. Its critical temperature of 18.3 K is the highest of conventional metallic superconductors.

About 85% of the world's niobium production is used in steels. The addition of small amounts (0.01 to 0.1%) of niobium to steels produces spectacular improvements in their mechanical properties. Niobium forms finely dispersed carbonitrides that refine the grain size and significantly increase strength while maintaining ductility and weldability.

HSLA steels micro-alloyed with niobium are used extensively in oil and gas transport pipelines, automotive structures (weight reduction and safety improvement), and construction. These applications represent several million tons of niobium steel produced annually. Niobium-stabilized stainless steels (types 347 and 348) resist intergranular corrosion in the chemical and nuclear industries.

Niobium is synthesized in stars mainly by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during type II supernovae and neutron star mergers. The cosmic abundance of niobium is extremely low, about 7×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen, making it one of the rarest elements in the universe.

Niobium-92, a radioactive isotope with a very long half-life (34.7 million years), was present during the formation of the solar system but is now completely decayed. It has been indirectly detected in some primitive meteorites. The initial ⁹²Nb/⁹³Nb ratio provides constraints on the time between nucleosynthesis and the formation of the first solids in the solar system.

N.B.:

Niobium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.0020% by mass (20 ppm), comparable to lithium. The main ore is pyrochlore (NaCaNb₂O₆F) containing 55-65% Nb₂O₅. Brazil dominates world production with 85-90% of the supply, mainly from the Araxá mine, which produces more than 150,000 tons of ferroniobium per year.

Metallic niobium is produced by aluminothermy for ferroniobium, or by magnesiothermic reduction of pentachloride (NbCl₅) for high-purity niobium intended for superconducting applications. Total world production is about 100,000 tons of contained niobium per year. The price of ferroniobium ranges between 40 and 50 dollars per kilogram, while high-purity niobium reaches 200-400 dollars per kilogram.

Niobium is considered a critical material by the European Union and the United States due to its strategic importance for the steel, aerospace, and energy industries, combined with the strong geographical concentration of its production in Brazil. Global demand is growing steadily by 3-5% per year.