Astatine holds a unique record: it is the rarest natural element on Earth. Estimates suggest that the total amount of astatine present in the Earth's crust at any given time is less than 30 grams. This extreme rarity is due to the fact that all its isotopes are radioactive with very short half-lives. The longest-lived, astatine-210, has a half-life of only 8.1 hours. Thus, any primordial astatine present during the formation of the Earth has long since decayed. The astatine present today is constantly recreated as an intermediate decay product in the natural uranium and thorium decay chains, but it disappears almost immediately.

Several isotopes of astatine appear in the decay chains of uranium and thorium, through beta decays of their parent elements, polonium or bismuth. For example:

These isotopes are produced in infinitesimal quantities and have such short lifetimes that they cannot accumulate.

Apart from radioactive decay, astatine can be produced naturally, in even smaller quantities, by cosmic spallation: when high-energy cosmic rays strike heavier nuclei such as lead or bismuth in the Earth's crust, they can fragment them and produce exotic nuclei, including astatine.

Astatine is located in a region of the periodic table where nuclear stability is very low. The study of its isotopes, particularly those with a "magic" number of neutrons (such as \(^{211}\mathrm{At}\) with 126 neutrons, a magic number), helps nuclear physicists refine models of nuclear structure and understand the limits of heavy nucleus stability.

The existence of astatine was predicted by Dmitri Mendeleev as early as the creation of his periodic table in 1869. He gave it the provisional name of "eka-iodine", predicting that it would be a halogen heavier than iodine, with similar chemical properties but a higher atomic mass and probably metallic characteristics. The search for this missing element mobilized several chemists for decades, without success, due to its extreme instability.

Astatine was finally artificially produced in 1940 by a team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley: Dale R. Corson, Kenneth Ross MacKenzie, and Emilio Segrè. They bombarded a bismuth-209 target with alpha particles accelerated in Berkeley's 60-inch cyclotron. The nuclear reaction produced astatine-211:

\(^{209}\mathrm{Bi} + \alpha \, (^{4}\mathrm{He}) \rightarrow \,^{211}\mathrm{At} + 2n\)

They identified it by its characteristic radioactivity and initially named it "alabamine" (symbol Ab), but this name was not retained.

After World War II, in 1943, Berta Karlik and Traude Bernert succeeded in identifying traces of astatine (the isotopes \(^{218}\mathrm{At}\) and \(^{219}\mathrm{At}\)) in natural decay products of uranium and thorium, thus confirming that it does exist in nature, albeit in infinitesimal quantities. The final name, "astatine" (derived from the Greek astatos, αστατος, meaning "unstable"), was proposed by the discoverers and adopted, emphasizing its most striking property.

Today, astatine is produced exclusively artificially, mainly in particle accelerators (cyclotrons). The most common methods are:

Global production is extremely low, on the order of a few micrograms to a few milligrams per year, mainly in specialized research laboratories (United States, Russia, Europe, Japan). Its cost is astronomical (millions of dollars per gram, if one could even accumulate a gram), and there is no "market" in the conventional sense.

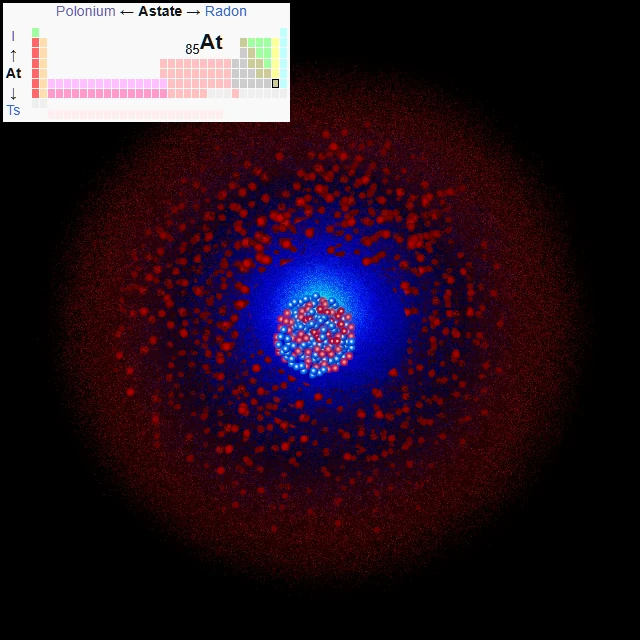

Astatine (symbol At, atomic number 85) is an element of group 17, the halogens. It is the heaviest and most radioactive member of this family, which includes fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, and tennessine. Its atom has 85 protons and, depending on the isotope, 116 to 140 neutrons. The most used isotope, \(^{211}\mathrm{At}\), has 126 neutrons. Its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁵, with seven valence electrons (6s² 6p⁵).

Due to its instability and the tiny amounts ever produced (it is estimated that less than a millionth of a gram of elemental astatine has ever been synthesized in total), most of its physical properties have never been directly measured on a macroscopic sample. They are deduced from theoretical calculations, extrapolations from halogen group trends, and studies on infinitesimal quantities.

Estimated melting point: ~575 K (~302 °C).

Estimated boiling point: ~610 K (~337 °C).

Chemically, astatine is expected to behave like a halogen, but with marked differences due to its weight and relativistic effects. It is expected to be the least reactive of the halogens and to exhibit metallic character (tendency to form cations, At⁺). Its possible oxidation states range from -1 to +7, with -1, +1, +3, +5, and +7 being plausible.

Atomic number: 85.

Group: 17 (Halogens).

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁵.

Physical state (20°C): Solid (predicted).

Radioactivity: All isotopes are radioactive.

Key medical isotope: \(^{211}\mathrm{At}\) (half-life 7.2 h, α emitter).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Production / Occurrence | Half-life / Decay mode | Remarks / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astatine-210 — \(^{210}\mathrm{At}\) | 85 | 125 | 209.987148 u | Synthetic / Natural trace | 8.1 hours (α, 99.8%; CE, 0.2%) | Isotope with the longest half-life (but less pure α than \(^{211}\mathrm{At}\)). |

| Astatine-211 — \(^{211}\mathrm{At}\) | 85 | 126 | 210.987496 u | Synthetic (α on Bi-209) | 7.214 hours (α, 100%) | The most important isotope. Pure high-energy alpha emitter (5.87 MeV). Ideal half-life for medicine (therapy). Target of choice for research. |

| Astatine-217 — \(^{217}\mathrm{At}\) | 85 | 132 | 216.992420 u | Produced in the decay chain of \(^{225}\mathrm{Ac}\) | 32.3 ms (α, 99.99%) | Decay product of actinium-225, used in targeted alpha therapy (TAT). Its chain produces three alpha particles. |

| Astatine-218 — \(^{218}\mathrm{At}\) | 85 | 133 | 217.995350 u | Natural trace (U-238 chain) | 1.5 s (α, 99.9%; β⁻, 0.1%) | Very fleeting natural isotope. |

| Astatine-219 — \(^{219}\mathrm{At}\) | 85 | 134 | 218.996590 u | Natural trace (U-235 chain) | 56 s (α, 97%; β⁻, 3%) | Natural isotope, longest half-life among natural astatines. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Astatine has 85 electrons distributed across six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁵ features seven valence electrons in the 6th shell (s² p⁵), a configuration characteristic of halogens. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(7), or fully: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁵.

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 7 electrons (6s² 6p⁵).

Astatine has 7 valence electrons (6s² 6p⁵). Like other halogens, it tends to gain an electron to achieve the stable configuration of the noble gas (radon), thus forming the astatide ion (At⁻). This is the -1 oxidation state, which should be the most stable. However, due to its large size and relativistic effects, astatine shows a strong tendency to exist in positive oxidation states, unlike lighter halogens. The +1 (At⁺), +3 (AtO⁻ or At³⁺), +5 (AtO₃⁻), and +7 (AtO₄⁻) states are possible and have been observed in trace compounds. This chemistry is more similar to that of iodine than to chlorine or bromine.

The chemistry of astatine has never been studied with visible samples. It is explored using trace radiochemistry techniques: the behavior of a few atoms or molecules labeled by the radioactivity of astatine in ultra-dilute solutions is tracked. This allows the determination of properties such as partition coefficients, redox potentials, or the stability of different complexes.

Studies confirm that astatine behaves like a halogen:

But it also shows differences:

This is the most promising and practically the only application. Astatine-211 is a pure alpha emitter ideal for targeted internal radiotherapy:

To guide astatine-211 to the tumor, it must be covalently and stably attached to a vector molecule that specifically recognizes cancer cells. These bioconjugates are major chemical challenges because the At-C (carbon-astatine) bond is relatively weak and sensitive to deastatination (loss of the astatine atom). The vectors studied include:

Preclinical and clinical trials (phases I/II) with \(^{211}\mathrm{At}\) focus on:

Preliminary results are encouraging, showing antitumor efficacy with limited toxicity.

Astatine-211 shares with polonium-210 an extreme radioactive toxicity in case of incorporation, due to its high-energy alpha emission. Its danger is even greater in some respects:

Handling of astatine-211 is done exclusively in high-security laboratories (P3 level) equipped with sealed glove boxes under controlled atmosphere (nitrogen or argon). Protection against alpha emissions is simple (gloves, box), but prevention of incorporation (inhalation of vapors, ingestion, skin contact) is paramount. All operations are designed to work with activities on the order of gigabecquerels (GBq) in minuscule volumes.

There is no specific antidote. Prevention is the only effective strategy. In case of suspected contamination, emergency measures (decontamination, monitoring of excreta) and administration of stable iodine (to saturate the thyroid and limit astatine uptake) could be considered, although their efficacy is unproven.

Like polonium and other Category 1 radioactive materials, astatine-211 is subject to the strictest IAEA regulations regarding nuclear safety and security. Its transport is highly regulated (ADR/RID regulations for radioactive materials). Only a few laboratories worldwide are authorized to produce and handle it.

The main obstacle to the development of astatine-211 therapies is its limited production. It requires a medium-energy cyclotron (~30 MeV) with a dedicated beamline for bismuth bombardment. The chemical separation of astatine from molten bismuth (distillation method) or in solution is complex and must be rapid. Developing more efficient production methods and logistics to deliver the isotope to hospitals within hours of production is an active area of research.

The future of astatine is almost entirely linked to theranostic nuclear medicine:

Astatine, this "phantom" of the periodic table, could thus move from the status of a laboratory curiosity to that of a life-saving precision therapeutic tool, embodying the paradox of radioelements: destructive power channeled toward healing.