Rubidium was discovered in 1861 by German chemists Robert Bunsen (1811-1899) and Gustav Kirchhoff (1824-1887) at the University of Heidelberg. This discovery marked a turning point in the history of chemistry as it was the first identification of a new chemical element made exclusively by spectroscopy, a revolutionary technique that Bunsen and Kirchhoff had just developed.

By analyzing the emission spectrum of a mineral water sample from Dürkheim, a German spa, Bunsen and Kirchhoff observed two intense, characteristic dark red spectral lines that had never been recorded before. These lines, located at 780.0 nm and 794.8 nm, did not correspond to any known element and indicated the presence of a new element in the sample.

The two chemists chose the name rubidium from the Latin rubidus, meaning dark red or the deepest red, in reference to the intense red spectral lines that revealed its existence. After identifying the element by spectroscopy, Bunsen succeeded in isolating a small amount of metallic rubidium in 1863 by electrolysis of molten rubidium chloride.

The discovery of rubidium, followed shortly by that of cesium by the same researchers, demonstrated the power of spectroscopic analysis as a tool for discovering chemical elements. This technique made it possible to identify elements present in minute quantities, opening a new era in the exploration of the chemical composition of matter. Bunsen and Kirchhoff thus laid the foundations of modern spectroscopy, a technique that would revolutionize not only chemistry but also astronomy.

Rubidium (symbol Rb, atomic number 37) is an alkali metal in group 1 of the periodic table. Its atom has 37 protons, usually 48 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{85}\mathrm{Rb}\)) and 37 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 5s¹.

Rubidium is a soft, silvery-white, and highly reactive metal. It is soft enough to be cut with a knife, leaving a shiny surface that quickly tarnishes in air by forming an oxide layer. Its density is 1.53 g/cm³, making it lighter than water, and it is the second least dense element of all metals after lithium among the alkali metals.

Rubidium has a very low melting point of 39.3 °C (312.5 K), which means it can melt in the hand by simple contact (although this is extremely dangerous due to its reactivity). It is one of the four metals that are liquid or nearly liquid at room temperature or slightly above, along with mercury, gallium, and cesium.

Rubidium boils at 688 °C (961 K), producing a characteristic blue-violet vapor. Metallic rubidium must be stored under an inert atmosphere (argon) or in mineral oil to protect it from oxidation and atmospheric moisture.

Melting point of rubidium: 312.5 K (39.3 °C).

Boiling point of rubidium: 961 K (688 °C).

Rubidium has the lowest ionization energy of all non-radioactive elements (403 kJ/mol).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubidium-85 — \(\,^{85}\mathrm{Rb}\,\) | 37 | 48 | 84.911789 u | ≈ 72.17 % | Stable | Major stable isotope of natural rubidium. Used in commercial atomic clocks. |

| Rubidium-87 — \(\,^{87}\mathrm{Rb}\,\) | 37 | 50 | 86.909180 u | ≈ 27.83 % | ≈ 4.88 × 10¹⁰ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Extremely long half-life. Decays into strontium-87, used in geochronological dating. |

| Rubidium-82 — \(\,^{82}\mathrm{Rb}\,\) | 37 | 45 | 81.918209 u | Synthetic | ≈ 1.27 minutes | Radioactive (β⁺). Positron emitter used in cardiac PET imaging to assess myocardial perfusion. |

| Rubidium-83 — \(\,^{83}\mathrm{Rb}\,\) | 37 | 46 | 82.915110 u | Synthetic | ≈ 86.2 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Used in medical research and nuclear physics. |

| Rubidium-84 — \(\,^{84}\mathrm{Rb}\,\) | 37 | 47 | 83.914385 u | Synthetic | ≈ 32.8 days | Radioactive (β⁺, β⁻, electron capture). Produced in nuclear reactors, used as a tracer. |

| Rubidium-86 — \(\,^{86}\mathrm{Rb}\,\) | 37 | 49 | 85.911167 u | Synthetic | ≈ 18.6 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Beta emitter used in nuclear medicine and as a tracer in biology. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Rubidium has 37 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is : 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 5s¹, or simplified: [Kr] 5s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(8) O(1).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic shielding that protects the valence electron.

N shell (n=4): contains 8 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶, forming the krypton noble gas configuration.

O shell (n=5): contains 1 single electron in the 5s subshell. This single electron is the valence electron of rubidium.

The single electron in the outer shell (5s¹) is the valence electron of rubidium. This electron is very weakly bound to the nucleus due to the large distance separating it from the nucleus and the significant shielding effect of the complete inner electron shells. This low ionization energy (403 kJ/mol, the lowest among stable elements) gives rubidium exceptional chemical reactivity.

The oxidation state of rubidium is exclusively +1 in all its chemical compounds. Rubidium easily loses its valence electron to form the Rb⁺ ion with the stable electronic configuration of krypton [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶. This complete octet configuration makes the rubidium ion particularly stable.

The ionic radius of Rb⁺ (152 pm) is significantly larger than that of potassium K⁺ (138 pm) and smaller than that of cesium Cs⁺ (167 pm), reflecting its intermediate position in group 1. This intermediate size influences its chemical properties and its ability to substitute other alkali ions in crystalline structures and biological systems.

The very low electronegativity of rubidium (0.82 on the Pauling scale) indicates that its chemical bonds are almost entirely ionic. Rubidium forms ionic compounds with practically all non-metals, notably halogens, oxygen, and sulfur. The extremely pronounced metallic character of rubidium makes it one of the most electropositive elements in the periodic table.

Rubidium is one of the most reactive metals in the periodic table, surpassed only by cesium and francium (radioactive). It reacts violently and spontaneously with water at room temperature, producing rubidium hydroxide and hydrogen gas: 2Rb + 2H₂O → 2RbOH + H₂. This reaction is so exothermic that the hydrogen produced ignites immediately, producing a characteristic red-violet flame due to vaporized rubidium.

Rubidium oxidizes instantly in air, first forming a layer of rubidium oxide (Rb₂O), then quickly rubidium peroxide (Rb₂O₂) and rubidium superoxide (RbO₂) in the presence of oxygen. The reaction is so rapid that a freshly cut surface of rubidium loses its metallic luster in a few seconds: 4Rb + O₂ → 2Rb₂O or Rb + O₂ → RbO₂ (in excess oxygen).

With halogens, rubidium reacts with explosive violence. The reaction with chlorine is particularly spectacular: 2Rb + Cl₂ → 2RbCl, producing an intense flame and white smoke of rubidium chloride. The rubidium halides (RbF, RbCl, RbBr, RbI) are very stable, white ionic solids and highly soluble in water.

Rubidium reacts vigorously with acids, even diluted, to form rubidium salts and release hydrogen: 2Rb + 2HCl → 2RbCl + H₂. This reaction is extremely dangerous due to the heat released and the likely ignition of hydrogen.

Like other alkali metals, rubidium dissolves in liquid ammonia to form blue conductive solutions containing solvated electrons. These solutions are used as powerful reducing agents in chemical synthesis. Rubidium also forms amalgams with mercury and alloys with other alkali metals.

Rubidium reacts directly with hydrogen at high temperature to form rubidium hydride (RbH), a very reactive white ionic compound. With sulfur, it forms rubidium sulfide (Rb₂S), and with nitrogen at very high temperature, it can form rubidium nitride (Rb₃N), although this reaction is difficult to achieve.

Rubidium plays a crucial role in modern time standards thanks to rubidium atomic clocks. These devices exploit the hyperfine transition of the rubidium-87 atom at a frequency of 6,834 682 610 904 29 GHz, which serves as an extremely stable reference for measuring time.

Rubidium atomic clocks are more compact, less expensive, and more robust than cesium clocks, although slightly less accurate. They offer frequency stability on the order of 10⁻¹² to 10⁻¹³, which corresponds to a drift of less than one second every 300,000 to 3 million years. This extraordinary precision makes them ideal for embedded applications requiring high temporal stability.

GPS (Global Positioning System) satellites carry atomic clocks, some of which use rubidium as a reference. The precision of GPS positioning depends directly on the temporal synchronization between satellites and ground receivers. A one-microsecond error in time measurement results in a position error of about 300 meters.

Rubidium atomic clocks are also used in telecommunications networks to synchronize equipment, in mobile phone base stations, in maritime and air navigation systems, and in many scientific applications requiring an ultra-stable time reference.

Rubidium is synthesized in stars mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, as well as by minor contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Rubidium-87, the heaviest isotope, is preferentially formed by the s-process.

The cosmic abundance of rubidium is about 1×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it relatively rare in the universe. This rarity is explained by its position beyond the iron peak in the nuclear stability curve and by the difficulties of synthesizing nuclei in this atomic mass region.

Rubidium-87 is a natural radioactive isotope with a very long period (half-life of 48.8 billion years, about 3.5 times the age of the universe). It decays by beta emission into stable strontium-87. This extremely slow decay makes the rubidium-strontium system a fundamental geochronological tool for dating ancient rocks and meteorites.

The rubidium-strontium dating method is based on the measurement of the isotopic ratio ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr and the ratio ⁸⁷Rb/⁸⁶Sr in minerals. This technique has made it possible to determine the age of the Earth (about 4.54 billion years), the age of the oldest terrestrial rocks (over 4 billion years), and the formation age of many meteorites, thus providing essential constraints on the history of the solar system.

The spectral lines of neutral and ionized rubidium (Rb I, Rb II) can be observed in the spectra of certain cool K and M type stars, as well as in red giant stars enriched in s-elements. The analysis of these lines makes it possible to study the stellar chemical composition and to trace the progressive enrichment of galaxies in heavy elements during cosmic evolution.

In the solar system, rubidium shows interesting isotopic variations between different types of meteorites, reflecting the formation conditions and thermal history of their parent bodies. These variations provide information on planetary differentiation processes and the chronology of events in the early solar system.

N.B.:

Rubidium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.0090% by mass (90 ppm), making it more abundant than copper, zinc, or lead. Despite this relative abundance, rubidium does not form its own ores and is always found associated with other elements, mainly in potassium minerals with which it is chemically very similar.

The main sources of rubidium are lithium minerals such as lepidolite (lithium mica) which can contain up to 3.5% rubidium, pollucite (cesium and rubidium silicate), and certain micas such as biotite. Rubidium is also present in carnallite (potassium ore) and in the mother liquors of potassium salt deposits.

Global production of metallic rubidium is very low, on the order of 2 to 3 tons per year, mainly extracted in Canada, the United States, and China. Rubidium is generally extracted as a by-product of lithium and cesium production. Extraction is done by complex chemical processes including selective precipitation, ion exchange, and electrochemical reduction.

Metallic rubidium is an extremely expensive niche product, with prices that can exceed 50,000 euros per kilogram for pure metal. Rubidium compounds such as chloride (RbCl) or carbonate (Rb₂CO₃) are less expensive but remain specialized chemicals reserved for research and high-tech applications.

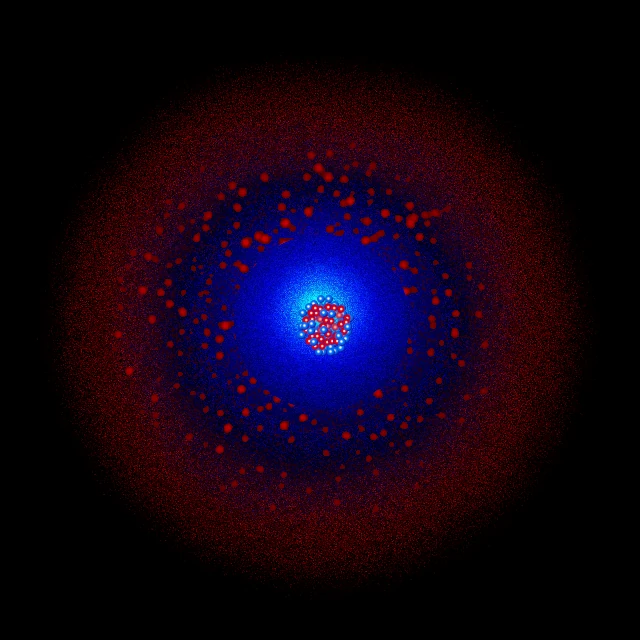

The rubidium market is dominated by applications in electronics and time metrology. The demand is relatively stable but limited, with potential growth linked to the development of quantum technologies, compact atomic clocks, and new space navigation systems. Research on Bose-Einstein condensates and quantum computing could stimulate future demand for high-purity rubidium.