Rhenium is synthesized in stars mainly through the r-process (rapid neutron capture) that occurs during cataclysmic events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. As a heavy element with an odd atomic number (Z=75), it is produced less efficiently than its even-numbered neighbors (tungsten-74 and osmium-76) according to the Oddo-Harkins rule. Rhenium shows a significant contribution from the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch), but the r-process dominates, accounting for 70-80% of its solar abundance.

The cosmic abundance of rhenium is about 5.0×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the rarest natural elements, comparable to gold and platinum, and about 10 times rarer than tungsten. Its extreme rarity is explained by its odd atomic number and its dominant production by the r-process, which is less frequent than the s-process. In the solar system, rhenium is one of the least abundant elements, with an estimated abundance of about 0.5 ppb (parts per billion) in the Earth's crust.

The rhenium-osmium isotopic system (¹⁸⁷Re → ¹⁸⁷Os) is an important chronological tool in geochemistry and cosmochemistry. Rhenium-187 is a radioactive isotope (half-life of 41.6 billion years) that decays into osmium-187 via beta decay. The importance of this system lies in the fundamental geochemical difference between these two elements: rhenium is moderately siderophile (prefers metal) and chalcophile (prefers sulfides), while osmium is strongly siderophile. Thus, during the formation of the Earth's core and the differentiation of planetary bodies, the Re/Os ratio varies considerably between the mantle and the core.

The Re-Os system is used to date a variety of geological processes: formation of the Earth's core, age of mantle rocks, metallogeny of sulfide deposits, and origin of petroleums. In meteorites, Re-Os measurements provide information on early differentiation processes in the solar system. The system is particularly useful for dating ultramafic rocks (rich in olivine) and sulfides, which are difficult to date by other methods. The ¹⁸⁷Os/¹⁸⁸Os ratio is a powerful tracer of the evolution of the Earth's mantle and crustal contamination.

Rhenium is named after the Rhine (Latin: Rhenus), the European river that flows through several countries including Germany. This name was chosen by its discoverers, the German chemists Walter Noddack, Ida Tacke, and Otto Berg, to honor the Rhineland, an important industrial and scientific region of Germany. The choice of name followed the tradition of naming elements after geographical locations, although few elements are named after rivers.

Rhenium was discovered in 1925 by the German chemists Walter Noddack (1893-1960), Ida Tacke (who later became Ida Noddack, 1896-1978), and Otto Berg (1873-1939) at the Institute of Physics and Technology in Berlin. They analyzed platinum and columbite ores in search of the missing elements 43 (technetium) and 75 (rhenium) predicted by Mendeleev's periodic table. Using X-ray spectroscopy, they detected the characteristic lines of element 75 in columbite and isolated it from gadolinite. In 1928, they succeeded in extracting 1 gram of rhenium from 660 kg of molybdenite.

The first significant production of rhenium was achieved in 1928. Initial applications were limited due to the extreme rarity and high cost of the metal. It was not until after World War II that more efficient production methods were developed, mainly as a byproduct of molybdenum and copper ore processing. The true industrial importance of rhenium was not recognized until the 1950s-1960s with the development of superalloys for gas turbines.

Rhenium is one of the rarest natural elements on Earth, with a crustal abundance estimated at about 0.7 ppb (parts per billion). There are no primary rhenium mining deposits; it is always recovered as a byproduct of the processing of other metals, mainly:

Global rhenium production is about 50 to 60 tons per year. The main producers are Chile (about 50% of world production), the United States, Poland, Kazakhstan, and Armenia. Due to its extreme rarity and strategic applications, rhenium is one of the most expensive metals, with typical prices ranging from 1,000 to 3,000 dollars per kilogram (or more during supply tensions). Demand is mainly driven by the aeronautics industry (superalloys) and petrochemistry (catalysts).

Rhenium (symbol Re, atomic number 75) is a transition metal of the 6th period, located in group 7 (formerly VIIB) of the periodic table, with manganese and technetium. Its atom has 75 protons, usually 112 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{187}\mathrm{Re}\)) and 75 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁵ 6s². This configuration has five electrons in the 5d subshell and two in the 6s, with a half-filled 5d subshell (5 electrons out of 10), which contributes to its stability.

Rhenium is a silvery-white, shiny, very dense (21.02 g/cm³), hard metal with the third highest melting point of all elements after tungsten and carbon. It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature. Rhenium has a very high modulus of elasticity (about 463 GPa), high tensile strength, and good ductility (for a refractory metal). Its electrical conductivity is moderate (about 28% that of copper) and its thermal conductivity is good.

Rhenium melts at 3186 °C (3459 K) - the third highest melting point among the elements - and boils at 5596 °C (5869 K). It has the widest liquid temperature range of all elements (2410 °C between melting and boiling). Rhenium retains its mechanical properties at high temperatures better than almost all other metals, with good creep resistance up to very high temperatures.

At room temperature, rhenium is relatively inert and resistant to corrosion due to a thin protective oxide layer. It does not dissolve in dilute hydrochloric or sulfuric acid, but is attacked by concentrated nitric acid and aqua regia. At high temperatures, it oxidizes to form rhenium heptoxide (Re₂O₇), a very volatile yellow solid. Rhenium reacts with halogens, sulfur, phosphorus, and other non-metals at high temperatures.

Melting point of rhenium: 3459 K (3186 °C) - 3rd highest among the elements.

Boiling point of rhenium: 5869 K (5596 °C).

Density: 21.02 g/cm³ - one of the densest metals.

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

Modulus of elasticity: 463 GPa - very rigid.

Hardness: 7.0 on the Mohs scale.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhenium-185 — \(\,^{185}\mathrm{Re}\,\) | 75 | 110 | 184.952955 u | ≈ 37.40 % | Stable | Stable isotope, used in some industrial and research applications. |

| Rhenium-187 — \(\,^{187}\mathrm{Re}\,\) | 75 | 112 | 186.955753 u | ≈ 62.60 % | 4.16×10¹⁰ years | Beta-minus radioactive with a very long half-life. Used in geochronology (Re-Os system). |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

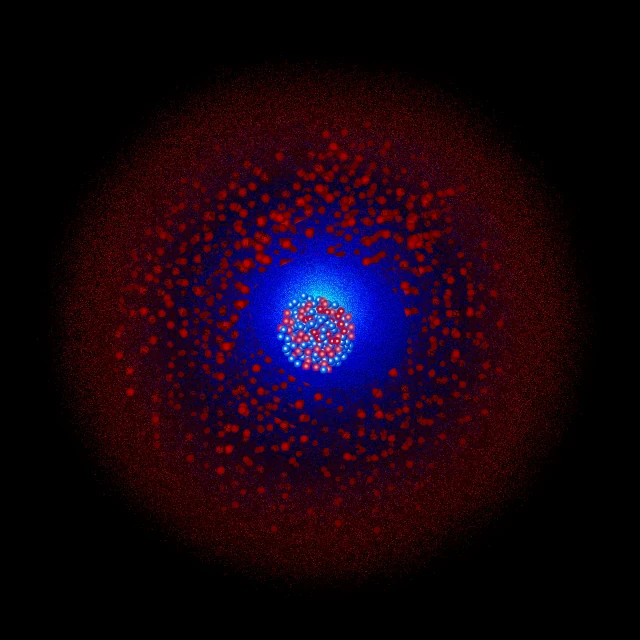

Rhenium has 75 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁵ 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and five electrons in the 5d subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(32) P(7), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d⁵ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic screening.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 32 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴ 5d⁵. The completely filled 4f subshell and the five 5d electrons (half-filled) give rhenium its transition metal properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 7 electrons in the 6s² and 5d⁵ subshells.

Rhenium effectively has 7 valence electrons: two 6s² electrons and five 5d⁵ electrons. Rhenium exhibits a wide range of oxidation states, from -3 to +7, with the states +7, +6, +4, and +3 being the most common and stable.

In the +7 oxidation state, rhenium loses its two 6s electrons and its five 5d electrons to form the Re⁷⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴. This state is represented by compounds such as Re₂O₇ (rhenium heptoxide) and perrhenates (ReO₄⁻). The +6 state is known in compounds such as ReO₃ and hexahalogenide complexes [ReCl₆]²⁻. The +4 state is important in compounds such as ReO₂ and ReS₂. The +3 state and lower states are often found in coordination complexes.

Rhenium has a particularly rich chemistry due to this wide variety of oxidation states and its ability to form multiple bonds with oxygen, halogens, and other ligands. Rhenium complexes are studied for their catalytic, photophysical, and medicinal properties. The half-filled 5d⁵ configuration in the atomic state contributes to the stability of certain oxidation states and the formation of compounds with interesting magnetic properties.

At room temperature, rhenium is stable in air due to a thin protective oxide layer. At high temperatures (above 300 °C), it oxidizes to form rhenium heptoxide (Re₂O₇): 4Re + 7O₂ → 2Re₂O₇. Re₂O₇ is a pale yellow, very volatile solid (sublimes at 360 °C) and hygroscopic, which dissolves in water to form perrhenic acid (HReO₄). Unlike most metals, rhenium does not form a stable protective oxide at high temperatures, which limits its use without protection in oxidizing atmospheres at high temperatures.

Metallic rhenium is resistant to most cold acids:

Rhenium dissolves in oxidizing alkaline solutions (such as NaOH + H₂O₂) to form perrhenates.

Rhenium reacts with halogens at moderate temperatures to form halides. With fluorine, it forms ReF₆ (hexafluoride, yellow liquid) and ReF₇ (heptafluoride, yellow solid). With chlorine, it forms ReCl₅ (pentachloride, brown-black solid) and ReCl₃ (trichloride, red solid). Rhenium reacts with sulfur at high temperatures to form the sulfide ReS₂ (lamellar structure similar to graphite), with phosphorus to form phosphides, and with carbon to form the carbide ReC. It also forms silicides, borides, and nitrides.

The most remarkable property of rhenium is its unique combination of mechanical properties at high temperatures. Unlike most metals, which rapidly lose their strength and ductility with increasing temperature, rhenium retains:

These properties, combined with its very high melting point, make rhenium an ideal material for very high temperature applications, particularly in superalloys for turbines.

The most important application of rhenium is its use in nickel-based superalloys for gas turbines in aircraft engines. About 70% of the world's rhenium production is used for this purpose. Superalloys containing rhenium are used in virtually all modern commercial and military aircraft engines, enabling spectacular gains in performance, efficiency, and reliability.

The addition of rhenium (typically 3-6% by weight) to nickel-based superalloys improves several critical properties:

Alloys containing rhenium allow:

A typical modern commercial aircraft engine contains 1-2 kg of rhenium, mainly in high-pressure turbine blades.

The second most important application of rhenium is its use as a catalyst in catalytic reforming, a key process in petroleum refining that converts heavy naphthas (low octane number) into high-octane products for gasoline. About 20% of the world's rhenium production is used for this purpose.

Modern reforming catalysts are typically bimetallic, containing platinum (0.3-0.6%) and rhenium (0.3-0.4%) supported on chlorinated alumina. Rhenium significantly improves the performance of platinum by:

Pt-Re catalysts allow:

A typical reforming reactor contains several tons of catalyst, with a few kilograms of rhenium per ton of catalyst. Used catalysts are regenerated and recycled, recovering some of the rhenium and platinum.

W/Re (tungsten-rhenium) type thermocouples are the only metallic thermocouples capable of measuring temperatures up to 2300 °C. They use tungsten and rhenium alloys as thermoelectric pairs:

Rhenium is used for filaments in X-ray tubes (often alloyed with tungsten) and as target material (anode) in X-ray tubes and X-ray fluorescence spectrometry devices. Its high melting point allows for higher power and longer lifetimes.

Rhenium-molybdenum and rhenium-tungsten alloys are used for electrical contacts in high-performance switches, relays, and circuit breakers. Rhenium improves resistance to electrical arcing and reduces contact erosion.

The isotope rhenium-188 (¹⁸⁸Re, half-life 17 hours) is used in nuclear medicine for radiotherapy. It emits high-energy beta particles (2.12 MeV maximum) and gamma rays (155 keV) allowing imaging. ¹⁸⁸Re is used for the treatment of cancers (liver, bone) and metastatic pain. It is produced from tungsten-188 (¹⁸⁸W/¹⁸⁸Re generator).

Rhenium is used in space propulsion systems:

Metallic rhenium and its insoluble compounds have low to moderate chemical toxicity. However, some soluble rhenium compounds, particularly perrhenates (ReO₄⁻), have moderate toxicity. Perrhenic acid (HReO₄) is corrosive. Rhenium dust can cause mechanical irritation. No carcinogenic effect has been clearly demonstrated for rhenium.

Radioactive isotopes of rhenium (such as ¹⁸⁶Re and ¹⁸⁸Re used in nuclear medicine) require radiation protection precautions during handling and use. Naturally radioactive rhenium-187 has very low activity due to its very long half-life (41.6 billion years) and does not pose a significant radiological risk.

The main environmental impact of rhenium is related to the extraction and processing of molybdenum and copper ores, of which it is a byproduct. Flotation, leaching, and smelting processes generate waste, wastewater, and emissions that must be controlled. However, since rhenium is produced in very small quantities (a few tens of tons per year), its direct environmental impact is limited compared to metals produced in large quantities.

Rhenium is recycled from several sources:

The recycling rate is estimated at 20-30%. Recycling is economically attractive due to the high price of rhenium, but technically difficult due to the low concentrations in waste. Recycling methods include hydrometallurgical (dissolution, solvent extraction, ion exchange) and pyrometallurgical processes.

Occupational exposure to rhenium occurs mainly in production and recycling plants, superalloy and catalyst manufacturers, and facilities using W/Re thermocouples. The main routes of exposure are inhalation of dust and fumes. Specific occupational exposure limits for rhenium are generally not established, but general recommendations for heavy metal dusts apply.