Molybdenum gets its name from the Greek word molybdos, meaning lead, because the mineral molybdenite (MoS₂) was long confused with galena (lead sulfide) and graphite due to their similar dark gray appearance and greasy texture. It was not until 1778 that the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742-1786), famous for discovering oxygen, chlorine, and several other elements, demonstrated that molybdenite was distinct from lead and graphite and contained a new element.

Scheele succeeded in obtaining molybdenum oxide (MoO₃) by treating molybdenite with nitric acid, but he did not manage to isolate the metal itself. In 1781, his compatriot Peter Jacob Hjelm (1746-1813), a Swedish metallurgist and chemist, succeeded in isolating molybdenum metal for the first time by reducing molybdenum oxide with carbon: MoO₃ + 3C → Mo + 3CO. The metal obtained was impure but marked the official discovery of molybdenum as an element.

For more than a century, molybdenum remained essentially a laboratory curiosity without practical applications. It was not until the early 20th century, with the development of alloy steels for armaments during World War I, that the importance of molybdenum was recognized. In 1913, the German company Krupp developed the first molybdenum steels for armor and cannons, revealing that small amounts of molybdenum dramatically improved the strength and toughness of steels at high temperatures.

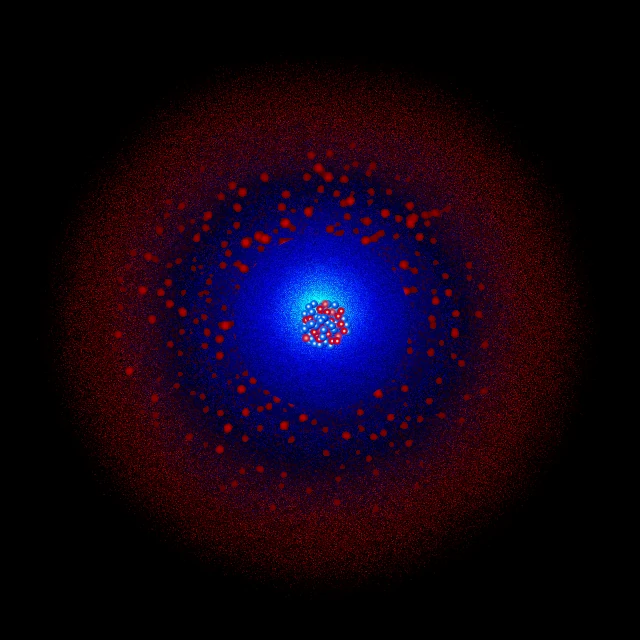

Molybdenum (symbol Mo, atomic number 42) is a transition metal in group 6 of the periodic table. Its atom has 42 protons, usually 56 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{98}\mathrm{Mo}\)) and 42 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s¹.

Molybdenum is a shiny silver-gray metal with an appearance similar to stainless steel. It has a density of 10.28 g/cm³, making it relatively heavy. Molybdenum is hard but ductile at room temperature and can be rolled into sheets or drawn into wires. Its hardness increases significantly with cold working.

Molybdenum crystallizes in a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure at all temperatures. It is a refractory metal with a very high melting point of 2623 °C (2896 K), the sixth highest melting point of all elements after carbon, tungsten, rhenium, osmium, and tantalum. It boils at 4639 °C (4912 K).

Molybdenum has exceptional thermal conductivity (138 W/m·K at 20 °C), close to that of copper, and high electrical conductivity. Its coefficient of thermal expansion is very low (4.8×10⁻⁶ K⁻¹), making it an ideal material for applications requiring dimensional stability at high temperatures.

Melting point of molybdenum: 2896 K (2623 °C).

Boiling point of molybdenum: 4912 K (4639 °C).

Molybdenum has the highest elastic modulus after tungsten among all pure metals.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molybdenum-92 — \(\,^{92}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 50 | 91.906811 u | ≈ 14.65 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope of natural molybdenum. |

| Molybdenum-94 — \(\,^{94}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 52 | 93.905088 u | ≈ 9.19 % | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope of natural molybdenum. |

| Molybdenum-95 — \(\,^{95}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 53 | 94.905842 u | ≈ 15.87 % | Stable | Third most abundant stable isotope of natural molybdenum. |

| Molybdenum-96 — \(\,^{96}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 54 | 95.904680 u | ≈ 16.67 % | Stable | Fourth most abundant stable isotope of natural molybdenum. |

| Molybdenum-97 — \(\,^{97}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 55 | 96.906022 u | ≈ 9.60 % | Stable | Fifth stable isotope. Has a nuclear spin used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Molybdenum-98 — \(\,^{98}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 56 | 97.905408 u | ≈ 24.39 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of molybdenum, accounting for nearly a quarter of the total. |

| Molybdenum-100 — \(\,^{100}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 58 | 99.907477 u | ≈ 9.63 % | ≈ 7.1 × 10¹⁸ years | Radioactive (β⁻β⁻). Extremely slow double beta decay, considered quasi-stable. |

| Molybdenum-99 — \(\,^{99}\mathrm{Mo}\,\) | 42 | 57 | 98.907712 u | Synthetic | ≈ 65.9 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Major fission product. Source of technetium-99m used in medical imaging. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Molybdenum has 42 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁵ 5s¹, or simplified: [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(13) O(1).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N Shell (n=4): contains 13 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁵. The five 4d electrons are valence electrons.

O Shell (n=5): contains 1 electron in the 5s subshell. This electron is also a valence electron.

Molybdenum has 6 valence electrons: five 4d⁵ electrons and one 5s¹ electron. The configuration [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s¹ with the half-filled 4d subshell is particularly stable. The most common oxidation state is +6, where molybdenum forms compounds such as molybdenum trioxide (MoO₃) and molybdates (MoO₄²⁻). The +5, +4, +3, +2, and 0 states also exist in various compounds.

Molybdenum(VI) dominates the chemistry of molybdenum, particularly in compounds with oxygen. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), where molybdenum is in the +4 state, is an important compound used as a solid lubricant. Organometallic complexes of molybdenum exhibit a wide variety of oxidation states and structures.

At room temperature, bulk molybdenum is relatively stable in air due to a thin protective oxide layer. It oxidizes slowly in humid air and more rapidly above 600 °C. At high temperatures (above 700 °C), molybdenum burns in oxygen to form white molybdenum trioxide: 2Mo + 3O₂ → 2MoO₃. The trioxide sublimes easily, forming characteristic white fumes.

Molybdenum resists corrosion by many acids at room temperature but is attacked by concentrated nitric acid and aqua regia. It reacts with alkaline solutions in the presence of oxidants to form molybdates. Halogens attack molybdenum at high temperatures to form various halides (MoF₆, MoCl₅, MoBr₃).

Molybdenum forms carbides (Mo₂C, MoC) and nitrides (MoN, Mo₂N) at high temperatures, all of which are very hard refractory ceramics used as cutting materials. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) has a layered structure similar to graphite, giving it excellent lubricating properties, particularly in vacuum environments where organic lubricants fail.

About 80% of the world's molybdenum production is used for steel alloys. Molybdenum significantly improves the properties of steels: it increases strength and hardness, improves hardenability (ability to harden in depth), maintains strength at high temperatures, and dramatically improves the corrosion resistance of stainless steels.

Austenitic and duplex stainless steels containing 2-4% molybdenum (types 316, 317, and duplex) exhibit exceptional resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion in chlorinated environments. These steels are essential in the chemical, oil, marine, and pharmaceutical industries. Molybdenum stabilizes the chromium oxide passive layer and prevents localized corrosion.

Tool steels containing 1-10% molybdenum retain their hardness and sharpness even at high temperatures (hot hardness phenomenon). These high-speed steels (HSS) allow high-speed machining without loss of performance. Micro-alloyed construction steels with molybdenum offer high mechanical strength while retaining excellent weldability.

Molybdenum is an essential trace element for all living organisms. In humans, it is a cofactor for several important enzymes, including xanthine oxidase (purine metabolism), aldehyde oxidase, and sulfite oxidase (detoxification of sulfites). Molybdenum is found in these enzymes in the form of a molybdenum-pterin cofactor (Moco).

The daily requirement for molybdenum for an adult is about 45 micrograms. Molybdenum deficiencies are extremely rare in humans because molybdenum is widespread in the diet (legumes, whole grains, green vegetables, nuts). Severe deficiency can cause serious neurological disorders. The toxicity of molybdenum is low, although prolonged excess can interfere with copper metabolism.

In nuclear medicine, molybdenum-99 (half-life 66 hours) is the source of technetium-99m (half-life 6 hours), the most widely used radioisotope in the world for diagnostic imaging. Mo-99 is produced by fission of uranium-235 in nuclear reactors and distributed to hospitals in technetium generators ("technetium cows"). More than 40 million Tc-99m imaging procedures are performed worldwide each year.

Molybdenum is synthesized in stars by several nucleosynthesis processes. Molybdenum isotopes are produced mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Molybdenum-92 and molybdenum-94 are also produced by the p-process (proton capture).

The cosmic abundance of molybdenum is about 2×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. The seven natural isotopes of molybdenum reflect the relative contributions of different nucleosynthesis processes, making molybdenum a key element for understanding these stellar mechanisms.

Isotopic variations of molybdenum in primitive meteorites provide information on the heterogeneity of the early solar system. Some meteorites show excesses of molybdenum-95 and molybdenum-97, suggesting variable contributions of the s and r processes in different regions of the solar nebula. These isotopic anomalies help trace the origin and evolution of planetary materials.

N.B.:

Molybdenum is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.00012% by mass (1.2 ppm), making it relatively rare. The main ore is molybdenite (MoS₂) containing about 60% molybdenum. Other sources include powellite (CaMoO₄) and wulfénite (PbMoO₄). The main deposits are found in China, the United States, Chile, Peru, and Canada.

China dominates world molybdenum production with about 40% of the supply, followed by Chile and the United States. Total world production is about 300,000 tons of contained molybdenum per year. Molybdenum is extracted either from primary molybdenite deposits or as a by-product of copper extraction in porphyry copper mines.

Molybdenum metal is produced by reducing molybdenum oxide (MoO₃) with hydrogen at high temperature: MoO₃ + 3H₂ → Mo + 3H₂O, followed by powder metallurgy sintering to obtain dense parts. Ferromolybdenum (iron-molybdenum alloy containing 60-75% Mo) is produced by aluminothermy and used directly in steel production. The price of molybdenum varies widely with economic cycles, typically ranging between 25 and 40 dollars per kilogram of contained molybdenum.