Promethium is the only rare earth element with no stable isotopes, a direct consequence of the valley of instability in which all its isotopes lie on the nuclear stability curve. Unlike other lanthanides, promethium does not occur naturally on Earth in detectable quantities; any primordial traces have completely disappeared since the formation of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago. The most stable isotope, Pm-145, has a half-life of only 17.7 years, insufficient to survive on geological timescales.

Promethium is nevertheless transiently synthesized in stars through the s-process (slow neutron capture) and r-process (rapid neutron capture). In asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, the s-process produces promethium as a radioactive intermediate that quickly decays into stable samarium before being ejected into the interstellar medium. During supernovae and neutron star mergers, the r-process generates substantial amounts of promethium, but it also decays into samarium within decades.

Spectral lines of promethium have been detected in the spectra of a few recent novae and supernovae, confirming its synthesis in these cataclysmic events. Spectroscopic observations of Supernova 1987A revealed potential signatures of promethium in the years following the explosion. These detections are extremely difficult because promethium is rapidly diluted and decays, making its spectral lines ephemeral and weak. Observing promethium in stellar ejecta provides valuable constraints on the timescales of explosive nucleosynthesis.

The total absence of promethium in the solar system and the interstellar medium confirms that the time interval between the nucleosynthesis of the last events enriching the presolar molecular cloud and the formation of the solar system was significantly longer than a few centuries. If the solar system had formed immediately after an enriching supernova, traces of promethium might have survived in primitive meteorites. The observed absence suggests a delay of at least several thousand years between the final nucleosynthesis and the collapse of the protosolar cloud.

Promethium is named after Prometheus, the Greek titan who stole fire from the gods to give to humans, symbolizing the difficult acquisition and potential danger of this radioactive element. The existence of an element with atomic number 61 was predicted by Dmitri Mendeleev in 1871 in his periodic classification, identifying a gap between neodymium (60) and samarium (62). Mendeleev named this hypothetical element "eka-neodymium" according to his systematic nomenclature.

Between 1902 and 1945, at least six groups of researchers claimed to have discovered element 61 in rare earth ores, proposing various names: "florentium" (Italians, 1924), "illinium" (Americans, 1926), and "cyclonium" (Americans, 1938). All these claims were later proven erroneous, resulting from spectroscopic misidentifications or contaminations. The impossibility of isolating element 61 from natural sources should have alerted researchers to its likely radioactive nature, but the concept of exclusively synthetic elements was not yet established.

The authentic discovery of promethium was made in 1945 by Jacob A. Marinsky, Lawrence E. Glendenin, and Charles D. Coryell at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, USA. Working on the Manhattan Project, they isolated and identified the isotope Pm-147 among the fission products of uranium-235 irradiated in a nuclear reactor. The identification was confirmed by X-ray spectroscopic analysis and characterization of radioactive decay.

The name "promethium" and the symbol "Pm" were officially adopted in 1949 by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), although the discoverers initially hesitated to name the element. Promethium thus became the first lanthanide discovered exclusively by artificial synthesis, foreshadowing the synthetic transuranic elements produced a few years earlier. The discovery marked an important step in recognizing that some elements predicted by the periodic table might not exist naturally on Earth.

Promethium does not occur naturally on Earth in measurable quantities. Trace amounts (less than 10⁻¹⁹ grams per ton) are produced by the spontaneous fission of uranium in uranium ores, but these quantities are totally negligible. Global production of promethium is entirely synthetic, obtained by extracting fission products from nuclear reactors. Annual global production is estimated at about 100-200 grams of Pm-147, mainly in the United States and Russia.

Promethium is extracted from spent nuclear fuel rods through complex solvent extraction and ion exchange chromatography processes. Pm-147 accounts for about 2-3% of fission products after several years of cooling. Extraction requires highly specialized facilities with radiation shielding and strict containment. The cost of purified promethium is extremely high, ranging from 1000 to 10,000 dollars per gram depending on purity, limiting its use to highly specialized applications where no alternative exists.

There is no recycling of promethium because the quantities used are minute and devices containing promethium (luminous sources, sensors) are generally hermetically sealed and treated as radioactive waste at the end of their life. Recovery would be technically possible but economically unviable given the small quantities and the costs of handling radioactive material.

Promethium (symbol Pm, atomic number 61) is the fifth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the rare earths of the f-block in the periodic table. Its atom has 61 protons, usually 86 neutrons (for the most used isotope \(\,^{147}\mathrm{Pm}\)), and 61 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁵ 6s².

Promethium metal has only been produced in microscopic quantities, limiting precise measurements of its physical properties. Available data mainly come from extrapolations based on neighboring lanthanides and a few measurements on milligram samples. Promethium is assumed to be a shiny, silvery-white metal that oxidizes rapidly in air. It probably crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure at room temperature, like its neighbors neodymium and samarium.

Promethium melts at about 1042 °C (1315 K) and boils at about 3000 °C (3273 K), according to estimates based on lanthanide trends. Its density is estimated at 7.26 g/cm³, consistent with lanthanide contraction. Promethium is expected to be a good conductor of electricity and heat, with typical metallic properties of lanthanides. Promethium is assumed to be paramagnetic at room temperature, with magnetic properties determined by the 4f⁵ configuration.

All isotopes of promethium are radioactive. The most used isotope, Pm-147, emits low-energy beta rays (maximum energy 224 keV, average energy 62 keV) without significant gamma emission. This pure low-energy beta emission makes Pm-147 a relatively safe radioactive source, as beta rays are stopped by a few millimeters of material and do not require heavy shielding. Pm-147 decays to stable samarium-147 with a half-life of 2.62 years.

Melting point of promethium: 1315 K (1042 °C) [estimated].

Boiling point of promethium: 3273 K (3000 °C) [estimated].

All promethium isotopes are radioactive; Pm-147 emits low-energy beta rays (half-life 2.62 years).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Origin | Half-life | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promethium-145 — \(\,^{145}\mathrm{Pm}\,\) | 61 | 84 | 144.912749 u | Synthetic | ≈ 17.7 years | Radioactive (EC, weak α). Most stable promethium isotope, but half-life insufficient for geological survival. |

| Promethium-146 — \(\,^{146}\mathrm{Pm}\,\) | 61 | 85 | 145.914696 u | Synthetic | ≈ 5.53 years | Radioactive (EC, β⁻). Emits intense gamma rays, requiring significant shielding. |

| Promethium-147 — \(\,^{147}\mathrm{Pm}\,\) | 61 | 86 | 146.915138 u | Synthetic | ≈ 2.62 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Most used isotope, pure low-energy beta emitter. Major fission product. |

| Promethium-148 — \(\,^{148}\mathrm{Pm}\,\) | 61 | 87 | 147.917475 u | Synthetic | ≈ 5.37 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Short half-life, used in nuclear research. |

| Promethium-149 — \(\,^{149}\mathrm{Pm}\,\) | 61 | 88 | 148.918334 u | Synthetic | ≈ 53.08 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Significant fission product, intermediate half-life. |

| Promethium-151 — \(\,^{151}\mathrm{Pm}\,\) | 61 | 90 | 150.921207 u | Synthetic | ≈ 28.40 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Fission product, used in radioactive decay studies. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

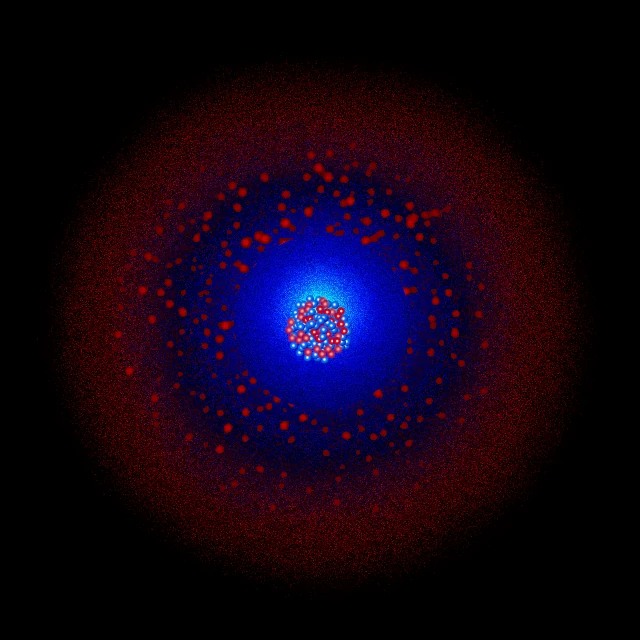

Promethium has 61 electrons distributed across six electron shells. Its electron configuration is [Xe] 4f⁵ 6s², typical of lanthanides where the 4f subshell is progressively filled. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(23) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f⁵ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable and complete structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 23 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f⁵ 5d⁰. The five 4f electrons characterize the chemistry of promethium.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of promethium.

Promethium effectively has 7 valence electrons: five 4f⁵ electrons and two 6s² electrons. The almost exclusive oxidation state is +3, characteristic of all lanthanides, where promethium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Pm³⁺ ion with the configuration [Xe] 4f⁴. This Pm³⁺ ion is responsible for the pale pink color of promethium solutions, although few direct observations exist due to the rarity of the element.

The chemistry of promethium is essentially the chemistry of the Pm³⁺ ion, with properties intermediate between neodymium and samarium. Promethium(III) compounds include the oxide Pm₂O₃, the chloride PmCl₃, the nitrate Pm(NO₃)₃, and various coordination complexes. Due to radioactivity, all promethium compounds undergo gradual self-radiolysis and may exhibit weak luminescence due to the excitation of surrounding molecules by beta rays.

Oxidation states +2 and +4 have been suggested under extreme conditions, but these states are extraordinarily unstable and have never been definitively characterized. The chemistry of promethium remains relatively understudied due to the difficulty of obtaining sufficient quantities, inherent radioactivity, and rapid decay that limits the duration of experiments.

Promethium metal is assumed to be very reactive with oxygen and oxidizes rapidly in air, forming a layer of promethium(III) oxide (Pm₂O₃) of variable color (probably pale pink to yellow). Studies on microscopic samples suggest that promethium ignites easily when heated in air, producing oxide with weak luminescence due to radioactivity: 4Pm + 3O₂ → 2Pm₂O₃. Handling promethium metal requires an inert atmosphere and appropriate containment against beta radiation.

Promethium is assumed to react slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water, producing promethium(III) hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas: 2Pm + 6H₂O → 2Pm(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. Aqueous solutions of promethium salts are pale pink and exhibit weak fluorescence due to the interaction of beta rays with water. Promethium(III) hydroxide easily precipitates from solutions as a gelatinous solid.

Promethium dissolves easily in acids, even diluted ones, with the release of hydrogen: 2Pm + 6HCl → 2PmCl₃ + 3H₂↑, producing pink Pm³⁺ solutions. Promethium forms halides (PmF₃, PmCl₃, PmBr₃, PmI₃), chalcogenides (Pm₂S₃, Pm₂Se₃), nitrides (PmN), and carbides (PmC, PmC₂). All these compounds are radioactive and undergo progressive degradation by self-radiolysis.

A unique property of promethium is the self-radiolysis of its compounds. The beta rays emitted by Pm-147 continuously break chemical bonds in solid compounds and solutions, producing free radicals, gases (H₂, O₂ in aqueous solutions), and progressive degradation of the crystalline structure. This self-radiolysis limits the lifespan of samples and can cause significant self-heating in concentrated sources. Promethium compounds must be periodically resynthesized to maintain their chemical integrity.

The main historical application of promethium was its use in autonomous luminescent paints for watch dials, aviation instruments, signage panels, and military devices. The principle is based on radioluminescence: the beta rays emitted by Pm-147 excite a phosphor (usually copper-doped zinc sulfide), which emits visible light. Unlike radium or tritium paints, Pm-147 produces more intense luminosity and does not require prior activation by light.

Promethium paints had several advantages: high initial luminosity (about 10 times higher than tritium), no gamma emission requiring shielding, and beta energy low enough to be stopped by the glass of the dial. However, the short half-life of Pm-147 (2.62 years) means that the luminosity decreases by half every 2.6 years, making devices unusable after 10-15 years. This limitation, combined with radiological safety concerns, led to the gradual abandonment of promethium in favor of tritium (half-life 12.3 years) in the 1970s-1980s.

The military extensively used promethium luminous sources for navigation instruments, weapon sights, control panels, and survival equipment during the 1960s-1970s. The higher light intensity was particularly appreciated for military applications where night visibility is critical. Some specialized aerospace applications continued to use promethium until the 1990s, although most were replaced by more durable alternatives or electroluminescent systems.

Pm-147 is used in industrial thickness gauges to accurately measure the thickness of materials in continuous production (paper, plastic, thin metal sheets). A sealed Pm-147 source emits beta rays through the material, and a detector on the other side measures the transmitted intensity. The attenuation of beta rays is proportional to the thickness and density of the material, allowing real-time quality control with micrometric precision.

Pm-147 has several advantages for this application: its moderate beta energy (maximum 224 keV) is ideal for measuring low to medium density materials and millimeter thickness, the absence of gamma emission eliminates the need for heavy shielding, and the source can be highly miniaturized. Promethium gauges are more compact and safer than alternatives using higher energy beta sources (Sr-90) or gamma sources (Cs-137).

The use of promethium in industrial gauges has significantly decreased since the 1990s due to the short half-life requiring frequent source replacement (every 5-10 years), strict regulations on radioactive materials, and limited availability. Most modern gauges use krypton-85, strontium-90 sources, or non-radioactive laser/optical systems. Only a few highly specialized applications requiring a compact geometry continue to use promethium.

Promethium was explored in the 1950s-1970s as a power source for miniature nuclear batteries and radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). In a nuclear battery, the kinetic energy of beta rays is directly converted into electricity by semiconductor junctions or betavoltaic materials. In an RTG, the heat produced by the absorption of beta rays is converted into electricity by thermocouples.

Pm-147 batteries were developed to power early pacemakers in the 1960s-1970s, offering 5-10 years of autonomy without battery replacement. Some experimental satellites and space probes also used small promethium RTGs for short-duration missions. The Soviet space program used Pm-147 sources in some navigation and communication satellites in the 1970s.

The use of promethium in nuclear batteries was largely abandoned in the 1980s due to the short half-life limiting device lifespan, the relatively low energy density compared to plutonium-238 for space RTGs, and safety concerns. Modern pacemakers use rechargeable lithium-ion batteries or long-life lithium-iodine systems. Modern space RTGs exclusively use plutonium-238 (half-life 87.7 years) for long-duration missions.

Promethium exhibits dual toxicity: chemical, comparable to other lanthanides, and radiological due to its beta emissions. Chemical toxicity is moderate, similar to neighboring rare earths. Ingestion or inhalation of promethium compounds causes preferential accumulation in the liver, kidneys, and bone skeleton. However, radiological toxicity dominates, as beta rays cause localized tissue damage and increase the long-term risk of cancer.

Exposure to promethium can occur through ingestion, inhalation of dust or aerosols, or skin absorption of soluble compounds. The beta rays of Pm-147 do not penetrate intact skin and are stopped by a few millimeters of tissue, but internal incorporation of promethium is dangerous because beta rays continuously irradiate surrounding tissues. Ingestion of 1 microcurie (37 kBq) of Pm-147 delivers a dose of about 0.5 millisieverts to the whole body, mainly to the liver and skeleton.

Promethium incorporated into the body behaves similarly to other lanthanides. The biological half-life (time to eliminate 50% of the body burden) is about 3-4 years for promethium deposited in the bone skeleton, and about 1 year for promethium in soft tissues. This prolonged retention combined with radioactivity makes promethium a particularly concerning internal contaminant. Chelating agents such as DTPA can accelerate elimination in cases of acute contamination.

Occupational exposure limits to promethium are strictly regulated. The annual limit on intake (ALI) for Pm-147 is typically set at 40-80 MBq (1-2 millicuries) for ingestion and 8-20 MBq (0.2-0.5 millicuries) for inhalation, depending on national regulations. Maximum permissible concentrations in air and water are on the order of 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁷ Bq/mL. Any handling of promethium requires strict containment procedures, personal protective equipment, and continuous radiological monitoring.

End-of-life promethium sources are classified as radioactive waste and must be managed according to strict nuclear waste management protocols. The relatively short half-life of Pm-147 (2.62 years) means that waste becomes radiologically negligible after about 26 years (10 half-lives). Old promethium luminescent paints found in vintage instruments pose a minor risk as most have decayed to very low levels.

Environmental contamination by promethium mainly comes from fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests (1950s-1960s) and nuclear accidents (Chernobyl, Fukushima). However, environmental promethium decays rapidly and has never been a major long-term contaminant. Current concentrations in the environment are totally negligible, well below detection thresholds. Nuclear fuel reprocessing sites may have locally elevated concentrations of promethium in liquid and solid waste, requiring appropriate containment.

The use of promethium will likely continue to decline due to the availability of safer and more durable alternatives for most applications. Luminous sources now use tritium (more durable) or electroluminescent systems (non-radioactive). Industrial gauges are evolving towards optical or laser technologies. Nuclear batteries for space applications favor plutonium-238. Promethium will probably remain confined to a few highly specialized niche applications where its unique properties (pure low-energy beta emitter) are irreplaceable, but the total quantities used will continue to decrease.