Nickel was first isolated in 1751 by the Swedish chemist and mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (1722-1765). Cronstedt extracted this new metal from a reddish-brown ore called kupfernickel (literally "devil's copper" in German), so named by miners who confused it with copper ore but obtained no copper from it. The name nickel comes from Nickel, a diminutive of Nikolaus, referring to a mischievous spirit from Germanic folklore said to have bewitched the ore. Although nickel-containing alloys had been used in China as early as 200 BC to make white coins called paitung, the elemental nature of nickel was not understood until Cronstedt's work. The chemical symbol Ni was internationally adopted in the 19th century.

Nickel (symbol Ni, atomic number 28) is a transition metal in group 10 of the periodic table. Its atom has 28 protons, usually 30 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{58}\mathrm{Ni}\)) and 28 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d⁸ 4s².

At room temperature, nickel is a solid, silvery-white metal with a slight golden tint, dense (density ≈ 8.908 g/cm³), and hard. It is one of the four natural ferromagnetic elements (along with iron, cobalt, and gadolinium), capable of being permanently magnetized. Nickel has excellent resistance to corrosion and oxidation, even at high temperatures, making it valuable for high-performance alloys. It is also ductile and malleable, allowing it to be easily worked. The melting point of nickel (liquid state): 1,728 K (1,455 °C). The boiling point of nickel (gaseous state): 3,186 K (2,913 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic Mass (u) | Natural Abundance | Half-Life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel-58 — \(\,^{58}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 30 | 57.935343 u | ≈ 68.08 % | Stable | Dominant isotope of natural nickel, the most abundant. |

| Nickel-60 — \(\,^{60}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 32 | 59.930786 u | ≈ 26.22 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope of nickel. |

| Nickel-61 — \(\,^{61}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 33 | 60.931056 u | ≈ 1.14 % | Stable | Only odd-odd stable isotope of nickel. |

| Nickel-62 — \(\,^{62}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 34 | 61.928345 u | ≈ 3.63 % | Stable | Has the highest binding energy per nucleon of all atomic nuclei. |

| Nickel-64 — \(\,^{64}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 36 | 63.927966 u | ≈ 0.93 % | Stable | Heaviest and least abundant stable isotope of natural nickel. |

| Nickel-56 — \(\,^{56}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 28 | 55.942132 u | Synthetic | ≈ 6.08 days | Radioactive, produced in large quantities in type Ia supernovae. Its decay to \(\,^{56}\mathrm{Co}\) and then to \(\,^{56}\mathrm{Fe}\) powers the luminosity of supernovae. |

| Nickel-59 — \(\,^{59}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 31 | 58.934347 u | Cosmic trace | ≈ 76,000 years | Long-lived radioactive isotope, used to date meteorites and study the history of the solar system. |

| Nickel-63 — \(\,^{63}\mathrm{Ni}\,\) | 28 | 35 | 62.929669 u | Synthetic | ≈ 100 years | Radioactive, used in explosive detectors and certain electronic devices. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

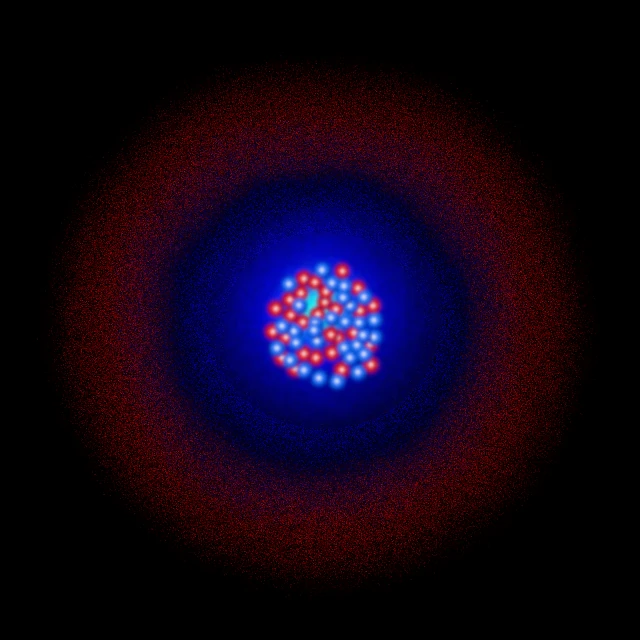

Nickel has 28 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁸ 4s², or simplified: [Ar] 3d⁸ 4s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(16) N(2).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 16 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d⁸. The 3s and 3p orbitals are complete, while the 3d orbitals contain 8 out of 10 possible electrons.

N Shell (n=4): contains 2 electrons in the 4s subshell. These electrons are the first to be involved in chemical bonding.

The 10 electrons in the outer shells (3d⁸ 4s²) are the valence electrons of nickel. This configuration explains its chemical properties:

By losing the 2 4s electrons, nickel forms the Ni²⁺ ion (oxidation state +2), the most common and stable state in aqueous solution.

By losing the 2 4s electrons and 1 3d electron, it forms the Ni³⁺ ion (oxidation state +3), less common but present in some compounds.

Oxidation states 0, +1, and +4 exist in specific compounds but are rare.

Nickel is a relatively unreactive metal at room temperature. It quickly forms a thin layer of nickel oxide (NiO) that protects it from further oxidation and corrosion. This natural passivation gives nickel its remarkable resistance to corrosion in air, fresh water, and seawater. Nickel does not react with bases and resists many dilute acids, but it dissolves slowly in dilute nitric acid and more rapidly in concentrated oxidizing acids. At high temperatures, nickel reacts with oxygen to form NiO, with sulfur to form sulfides, and with halogens to form halides. Nickel mainly forms compounds with an oxidation state of +2, whose salts are generally green in aqueous solution. Nickel can form coordination complexes with many ligands, an important property in catalysis.

Nickel holds a special place in astrophysics. The isotope \(\,^{62}\mathrm{Ni}\) has the highest binding energy per nucleon of all atomic nuclei, making it the most energetically stable nucleus. However, iron-56 is the most abundant final product of stellar fusion, as stellar nuclear reactions favor its formation. Nickel is mainly synthesized during silicon burning in massive stars at the end of their lives and during supernova explosions.

The radioactive isotope \(\,^{56}\mathrm{Ni}\) plays a crucial role in type Ia supernovae. Produced in large quantities during the explosion, its radioactive decay to cobalt-56 and then to iron-56 generates the energy that powers the characteristic luminosity of these supernovae for weeks. Observing this light curve allows astronomers to measure cosmic distances and study the expansion of the universe.

The long-lived isotope \(\,^{59}\mathrm{Ni}\) (76,000 years) serves as a tracer to date nucleosynthesis events in the early solar system. Its presence in ancient meteorites provides information on the nuclear processes that enriched the gas and dust cloud from which our solar system was born. The spectral lines of nickel in stars help determine their chemical composition and evolution.

N.B.:

Nickel is the 24th most abundant element in the Earth's crust (about 0.0089% by mass). However, it is much more abundant in the Earth's core, where it makes up about 5% of the composition alongside iron. Nickel is mainly found in ores such as pentlandite ((Fe,Ni)₉S₈), garnierite (nickel and magnesium silicate), and nickeliferous laterite. Iron meteorites contain significant proportions of nickel (5-20%), evidence of the composition of the cores of differentiated planets. Nickel extraction is mainly done by pyrometallurgical or hydrometallurgical processes depending on the type of ore, and the metal can be refined to high purity by the Mond process using gaseous nickel carbonyl Ni(CO)₄.