Terbium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) that occurs in AGB stars (asymptotic giants) of low to medium mass. Unlike europium, which is dominated by the r-process, terbium shows a significant contribution from the s-process, estimated at about 70-80% of its solar abundance. The rest comes from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae. This mixed but s-process-dominated origin classifies it among the "intermediate rare earths".

The cosmic abundance of terbium is about 1.7×10⁻¹² times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about 1.4 times more abundant than gadolinium but 5 to 6 times less abundant than cerium. This relative rarity is explained by its position in the "valley" of heavy rare earth abundances and by the fact that its nucleus has an odd number of protons (Tb, Z = 65), which tends to reduce its abundance according to the Oddo-Harkins rule (elements with even Z are generally more abundant than their odd-Z neighbors).

Terbium is an important tracer of the s-process in astrophysics. Its relative abundance compared to other lanthanides in stars of different generations allows quantifying the contribution of AGB stars to the chemical enrichment of the Galaxy. Stars enriched in s-process elements (such as barium stars) often show high Tb/Eu ratios, characteristic of nucleosynthesis dominated by the s-process rather than the r-process. The study of terbium in metal-poor stars helps date the appearance of the first AGB stars in the Universe.

The detection of terbium in stellar atmospheres is particularly difficult due to the weakness and overlap of its spectral lines with those of other elements. The lines of the Tb II ion (singly ionized terbium) are the most accessible, but they require high-resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio spectra. Despite these difficulties, terbium has been detected in some stars of the galactic halo and in stars enriched in s-process elements. These detections provide valuable constraints on models of stellar nucleosynthesis and on the relative efficiency of s and r processes in the production of heavy rare earths.

Terbium is named after the Swedish village of Ytterby, located on the island of Resarö near Stockholm. This small village has a feldspar and quartz quarry that provided several minerals containing rare earths. Ytterby is famous for giving its name to no less than four elements: yttrium (Y), terbium (Tb), erbium (Er), and ytterbium (Yb). The name "terbium" was formed by analogy with the other elements discovered in the minerals from this locality.

Terbium was discovered in 1843 by the Swedish chemist Carl Gustaf Mosander (1797-1858), who worked at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Mosander was studying a yttria mineral (yttrium oxide) from Ytterby. After multiple fractional crystallizations, he succeeded in separating this oxide into three distinct compounds which he named yttria (white), erbia (pink), and terbia (yellow). The "terbia" he had isolated contained mainly terbium oxide, although the complete purification of the element took several more decades.

For several years, there was confusion regarding the names "terbia" and "erbia". Some chemists swapped the names, attributing the name "terbia" to what we now call erbia (erbium oxide) and vice versa. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the nomenclature was definitively fixed according to Mosander's original discovery. The isolation of relatively pure metallic terbium was first achieved in 1905 by the French chemist Georges Urbain, who used electrolysis of molten terbium salts.

Terbium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 1.2 ppm (parts per million), making it one of the rarest lanthanides, comparable to lutetium and thulium. It is about 5 times less abundant than gadolinium. The main minerals containing terbium are bastnasite ((Ce,La,Nd,Tb)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Tb,Th)PO₄), where it typically represents 0.02 to 0.1% of the total rare earth content, and xenotime (YPO₄) where it can be more concentrated.

Global production of terbium oxide (Tb₄O₇) is about 10 to 15 tons per year, making it one of the least produced rare earths in terms of mass. Due to its rarity and high-value applications, terbium is one of the most expensive rare earths, with typical prices of $1,000 to $2,000 per kilogram of oxide (or more during demand peaks). China dominates production with over 90% of the global total.

Metallic terbium is produced mainly by metallothermic reduction of terbium fluoride (TbF₃) with metallic calcium in an inert argon atmosphere. Global annual production of metallic terbium is about 5 to 10 tons. Recycling of terbium from used fluorescent lamps and magnets is technically possible and economically interesting due to its high price, but large-scale recycling infrastructure is still limited.

Terbium (symbol Tb, atomic number 65) is the ninth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the rare earths of the f-block of the periodic table. Its atom has 65 protons, 94 neutrons (for the only stable isotope \(\,^{159}\mathrm{Tb}\)) and 65 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁹ 6s². This configuration gives terbium its characteristic magnetic and luminescent properties.

Terbium is a gray-silver metal, malleable, ductile, and soft enough to be cut with a knife. It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature. Terbium is strongly paramagnetic and becomes antiferromagnetic below 230 K (-43 °C), then ferromagnetic below 220 K (-53 °C). Its Curie temperature is 222 K (-51 °C). Although these temperatures are well below room temperature, terbium is crucial in magnetostrictive alloys such as Terfenol-D (Tb-Dy-Fe) which exhibit exceptional magnetic properties at room temperature.

Terbium melts at 1356 °C (1629 K) and boils at 3230 °C (3503 K). Like most lanthanides, it has high melting and boiling points. Terbium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 1289 °C where its crystal structure changes from hexagonal close-packed (HCP) to body-centered cubic (BCC). Its electrical conductivity is poor, about 30 times lower than that of copper. Terbium also exhibits giant magnetoresistance at low temperatures.

Terbium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, but oxidizes slowly to form Tb₄O₇ oxide (a mixture of Tb₂O₃ and TbO₂). It oxidizes more rapidly when heated. Terbium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form terbium(III) hydroxide Tb(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids. Metallic terbium must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere to prevent gradual oxidation.

Melting point of terbium: 1629 K (1356 °C).

Boiling point of terbium: 3503 K (3230 °C).

Curie temperature of terbium: 222 K (-51 °C) - ferromagnetic below.

Néel temperature (antiferromagnetic transition): 230 K (-43 °C).

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terbium-159 — \(\,^{159}\mathrm{Tb}\,\) | 65 | 94 | 158.925346 u | ≈ 100 % | Stable | Only natural stable isotope of terbium. Has 94 neutrons and is slightly fissile. |

| Terbium-157 — \(\,^{157}\mathrm{Tb}\,\) | 65 | 92 | 156.924023 u | Synthetic | ≈ 71 years | Radioactive (EC). Used in research and as a source for the production of medical isotopes. |

| Terbium-158 — \(\,^{158}\mathrm{Tb}\,\) | 65 | 93 | 157.925413 u | Synthetic | ≈ 180 years | Radioactive (EC, β⁺). Gamma emitter used in research and neutron activation analysis. |

| Terbium-160 — \(\,^{160}\mathrm{Tb}\,\) | 65 | 95 | 159.927167 u | Synthetic | ≈ 72.3 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Produced in nuclear reactors, used in research and nuclear medicine. |

| Terbium-161 — \(\,^{161}\mathrm{Tb}\,\) | 65 | 96 | 160.929369 u | Synthetic | ≈ 6.91 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Low-energy beta emitter, studied for targeted therapy applications (radiotherapy). |

N.B. :

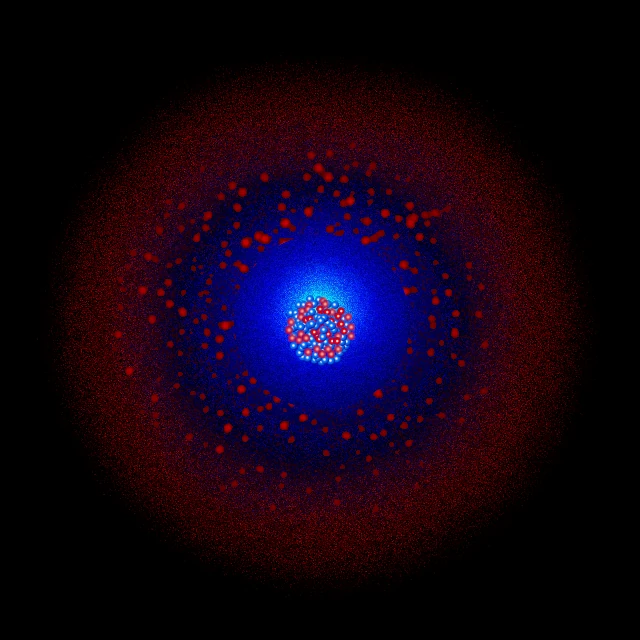

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Terbium has 65 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁹ 6s² has nine electrons in the 4f subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(27) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f⁹ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 27 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f⁹ 5d⁰. The nine 4f electrons give terbium its characteristic magnetic and luminescent properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of terbium.

Terbium effectively has 11 valence electrons: nine 4f⁹ electrons and two 6s² electrons. Terbium mainly exhibits the +3 oxidation state, which is by far the most stable and common. In this state, terbium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Tb³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁸. This ion has eight electrons in the 4f subshell and exhibits characteristic intense green luminescence.

Terbium can also form compounds in the +4 oxidation state, although these are much less stable and require oxidizing conditions. The Tb⁴⁺ ion has the configuration [Xe] 4f⁷ (half-filled), which gives it some stability, similar to that of the Gd³⁺ ion. Terbium(IV) compounds such as TbO₂ (terbium dioxide) exist but are powerful oxidants and easily decompose, releasing oxygen. A few rare terbium(II) compounds have also been synthesized under extreme conditions, but they are very unstable.

The chemistry of terbium is thus dominated by the +3 state. The Tb³⁺ ion has an ionic radius of 106.3 pm (for coordination number 8) and forms colorless or faintly colored (pale yellow) complexes in aqueous solution. Its coordination chemistry is rich, with a preference for oxygen-donor ligands. The luminescent properties of Tb³⁺ are particularly exploited in technological applications.

Terbium metal oxidizes slowly in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin layer of oxide that partially protects the underlying metal. When heated above 150-200 °C, oxidation accelerates and terbium burns to form mainly the mixed oxide Tb₄O₇ (which corresponds to Tb₂O₃·TbO₂): 8Tb + 7O₂ → 2Tb₄O₇. In fine powder form, terbium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air. Terbium(III) oxide Tb₂O₃ can be obtained by reducing Tb₄O₇ under a hydrogen atmosphere at high temperature.

Terbium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form terbium(III) hydroxide Tb(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Tb + 6H₂O → 2Tb(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous white solid with low solubility. As with other lanthanides, the reaction is not as vigorous as with alkali or alkaline earth metals, but it is noticeable and can be observed over the long term if the metal is exposed to moisture.

Terbium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides: 2Tb + 3F₂ → 2TbF₃ (white fluoride); 2Tb + 3Cl₂ → 2TbCl₃ (white chloride). Terbium dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) with hydrogen release and formation of the corresponding Tb³⁺ salts: 2Tb + 6HCl → 2TbCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Terbium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperatures (300-400 °C) to form TbH₂, then TbH₃ at higher temperatures. With sulfur, it forms the sulfide Tb₂S₃. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperature (>1000 °C) to form the nitride TbN, and with carbon to form the carbide TbC₂. Terbium also forms many coordination complexes with organic ligands, exploited in particular in luminescent markers and optical materials.

The most remarkable property of terbium is its intense green luminescence. The Tb³⁺ ion is one of the most luminescent lanthanide ions, emitting bright green light mainly around 545 nm (⁵D₄ → ⁷F₅ transition) when excited by UV (often around 254 nm or 365 nm). This pure green emission with high quantum yield (up to 90% in optimal matrices such as oxides or fluorides) makes terbium the standard green phosphor for many applications. The emission actually consists of several narrow lines corresponding to transitions to different ⁷FJ levels (J=6,5,4,3…), with the line at 545 nm being the most intense.

The application that made terbium famous was its use as the main activator in the green phosphors of high-efficiency, high-color-rendering "tri-phosphor" fluorescent lamps. The standard phosphor is lanthanum and cerium phosphate doped with terbium: LaPO₄:Ce³⁺,Tb³⁺ (often called LAP). In this material, Ce³⁺ ions efficiently absorb mercury UV radiation (254 nm) and transfer energy to neighboring Tb³⁺ ions, which then emit bright green light at 545 nm. Combined with blue (BaMgAl₁₀O₁₇:Eu²⁺) and red (Y₂O₃:Eu³⁺) phosphors, it produces high-quality white light with a color rendering index (CRI) above 80.

The LaPO₄:Ce³⁺,Tb³⁺ phosphor has an exceptional quantum yield (almost 100% under optimal conditions), high thermal and chemical stability, and pure green color. A typical 20W compact fluorescent lamp contains about 50-100 milligrams of this phosphor, corresponding to a few milligrams of terbium. This application represented for decades the largest share of global terbium consumption, before being gradually replaced by LEDs. The luminous efficacy of tri-phosphor lamps reaches 80-100 lumens per watt, 4 to 5 times that of incandescent lamps.

With the advent of white LEDs, terbium has found new applications in phosphor converters. For pure green LEDs, materials such as strontium aluminum silicate doped with terbium (SrAl₂O₄:Tb³⁺) or terbium-doped YAG are used. In white LEDs, mixtures of phosphors containing terbium (green) with blue and red phosphors allow a full spectrum and high CRI. Research is ongoing to develop terbium-doped nitride or oxynitride phosphors, offering better stability at high temperatures and increased efficiency.

Magnetostriction is the property of certain materials to change shape or dimensions under the influence of a magnetic field. Terfenol-D (trade name derived from TERbium, FE (iron), Naval Ordnance Laboratory, and D for dysprosium) is an alloy of approximate composition Tb0.3Dy0.7Fe₂ that exhibits giant magnetostriction at room temperature. It can elongate or contract by up to 0.1 to 0.2% of its length under the action of a magnetic field, which is about 50 to 100 times more than traditional magnetostrictive materials like nickel.

Terfenol-D is an alloy based on rare earths (terbium and dysprosium) and iron. The combination of terbium and dysprosium allows the adjustment of magnetic properties to obtain optimal magnetostriction at room temperature, while minimizing magnetic anisotropy. Iron provides magnetic coupling. The alloy is usually in the form of single crystals or directionally textured materials to maximize the effect in a preferred direction. The terbium content is crucial for performance but significantly contributes to the high cost of the material.

Terfenol-D is used in precision actuators (sonar transducers, magnetically controlled fuel injectors, micro- and nanometric positioning systems), sensors (force and torque sensors, hydrophones), ultrasonic transducers (medical imaging, ultrasonic cleaning), and vibration control systems (active damping). Its ability to convert magnetic energy into mechanical motion (and vice versa) with great force, rapid response, and high precision makes it a unique material for many high-tech applications. A typical actuator may contain from a few grams to several hundred grams of Terfenol-D.

Organic complexes of terbium (usually with β-diketonate ligands) exhibit intense green luminescence under UV illumination and a long fluorescence lifetime (on the order of milliseconds), making them ideal for security applications. They are used in printing inks for banknotes, passports, identity cards, pharmaceutical labels, and luxury goods. The green luminescence of terbium is often combined with the red luminescence of europium to create complex color effects that are difficult to reproduce.

Terbium-doped nanoparticles or microspheres can be incorporated into materials (plastics, paints, inks) to create invisible markers that are detectable by UV fluorescence. These markers enable product traceability, authentication, and counterfeit prevention. The unique spectral signature of terbium (characteristic narrow lines) allows unambiguous identification. More sophisticated systems use specific ratios of rare earth ions (including terbium) to create luminescent "barcodes".

Terbium chelates (for example with EDTA or derivatives) exhibit long-lived fluorescence, allowing their detection using time-resolved measurement techniques. This method effectively eliminates short-lived background fluorescence from biological components, significantly increasing the sensitivity of assays. Time-resolved fluorescence immunoassays (TRFIA) using terbium are used to measure hormones, tumor markers, viral antigens, etc., with very low detection limits.

Terbium complexes are being studied as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although they are less effective than gadolinium-based agents. Terbium-161 (⁶¹Tb) is a radioactive beta-emitting isotope under study for targeted cancer radiotherapy (theranostics), especially when coupled with molecules specifically targeting tumor cells. Research on terbium-doped nanoparticles for optical imaging and treatment is also active.

Terbium and its compounds exhibit moderate chemical toxicity, similar to other lanthanides. Soluble terbium salts can cause skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation. Inhalation of terbium compound dust can cause lung irritation. Toxicological studies indicate low to moderate acute toxicity, with median lethal doses (LD50) for terbium salts typically above 500-1000 mg/kg in rodents via oral route. No carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic effects have been clearly demonstrated for terbium.

Like other lanthanides, ingested or injected terbium accumulates mainly in the liver and bone skeleton. Its biological half-life is long (several years for the bone fraction). Terbium has no known biological role and is not considered an essential element. Due to its limited direct use in humans (except for research tracers), general population exposure is extremely low and comes mainly from diffuse environmental sources.

The main environmental concerns are associated with the extraction and refining of rare earths in general, not specifically with terbium. The extraction of one kilogram of terbium requires the processing of several hundred tons of ore, generating large volumes of waste, acidic waters, and sometimes radioactive residues (thorium, uranium). Mining sites can have significant impacts on soils, waters, and workers' health if practices are not controlled.

Terbium is classified as a "critical raw material" by the European Union and the United States due to its economic importance, strategic applications (defense, high technology), and the high geographical concentration of its production (China). Recycling of terbium from used fluorescent lamps, magnets, and electronic waste is therefore a priority to secure supply and reduce environmental impact. Recycling techniques (hydrometallurgy, pyrometallurgy) are operational but require efficient collection and sorting infrastructures. Current recycling rates are low (less than 1%) but are expected to increase with regulations on electrical and electronic equipment waste (WEEE) and rising prices.

Occupational exposure to terbium occurs mainly in rare earth production plants, phosphor manufacturing, and recycling facilities. There are no specific occupational exposure limits for terbium in most countries. General recommendations for rare earth dusts apply (typically 5-10 mg/m³ for respirable dust). Personal protective equipment (masks, gloves) and adequate ventilation are required in environments where terbium compound dust or aerosols are likely to be present.