Iodine was discovered in 1811 by the French chemist Bernard Courtois (1777-1838) in the ashes of seaweed (kelp) used for the production of saltpeter. Courtois was working in his family's saltpeter factory in Paris during the Napoleonic Wars, a time when saltpeter was crucial for the manufacture of gunpowder.

While treating seaweed ashes with concentrated sulfuric acid, Courtois observed the release of spectacular purple vapors that condensed into gray-black metallic crystals with violet reflections. This accidental discovery revealed a new chemical element with remarkable properties. Courtois, aware of the importance of his discovery but lacking the means to study it fully, shared samples with other chemists.

The properties of this new element were studied by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778-1850) and Humphry Davy (1778-1829) in 1813-1814. Gay-Lussac proposed the name iodine derived from the Greek iodes (ἰοειδής) meaning "violet" or "violet-colored," in reference to the characteristic color of the vapors. The chemical symbol I was immediately adopted.

The medical importance of iodine was gradually recognized in the 19th century. In 1820, the Swiss physician Jean-François Coindet (1774-1834) discovered that iodine could treat goiter, an endemic disease in iodine-poor mountainous regions. This discovery established iodine as the first trace element recognized as essential for human health.

N.B.:

Iodine is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.45 ppm, making it relatively rare, about 60 times less abundant than chlorine. However, iodine accumulates strongly in the oceans, where its concentration reaches about 0.06 mg/L, and is massively concentrated in seaweed, which can contain up to 0.5% of its dry weight in iodine.

The main iodine ores are rare. Iodine is mainly extracted from brines of nitrate deposits in Chile (caliche) and Japan, or recovered from oil and gas extraction brines. Seaweed (kelp, fucus) remains a traditional source of iodine in some regions. Sodium iodide and iodate are the main commercial compounds.

Global iodine production is about 30,000 to 35,000 tons per year. Chile dominates world production with about 55-60% of the total, followed by Japan (25-30%), the United States, and Turkmenistan. This geographical concentration makes iodine a strategically important material, especially for essential medical applications.

Iodine is considered a critical element by several countries due to its indispensable nature for public health and medical applications. Iodine recycling is limited, representing less than 5% of the supply, although recycling from used photographic solutions was historically important before the transition to digital photography.

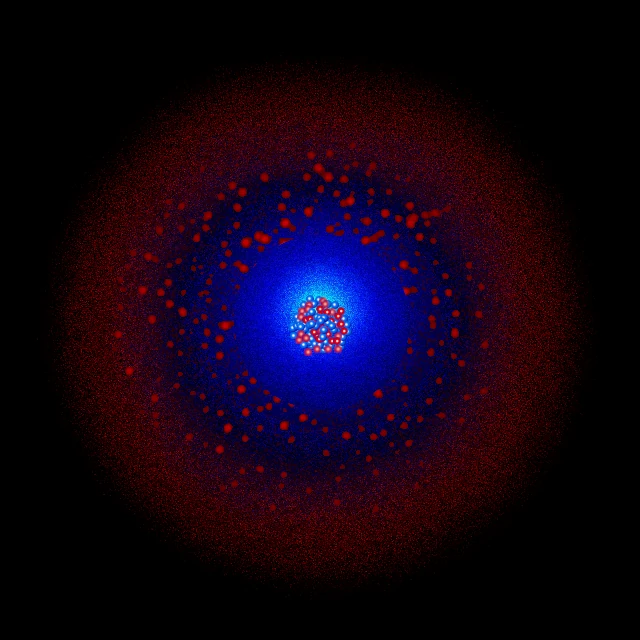

Iodine (symbol I, atomic number 53) is a halogen in group 17 of the periodic table, along with fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and astatine. Its atom has 53 protons, usually 74 neutrons (for the stable isotope \(\,^{127}\mathrm{I}\)) and 53 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁵.

Iodine is a gray-black to bluish-black crystalline solid with a pronounced metallic luster, exhibiting a lamellar structure. It has a density of 4.93 g/cm³, making it moderately dense. Iodine crystallizes in an orthorhombic structure forming diatomic molecules I₂ held together by van der Waals forces. Iodine crystals are brittle and easily break into shiny flakes.

Iodine melts at 113.7 °C (386.85 K) and boils at 184.3 °C (457.4 K). The most spectacular property of iodine is its ability to sublime easily at room temperature, passing directly from the solid to the gaseous state without intermediate melting. This sublimation produces characteristic intense purple vapors with a pungent and irritating odor.

Solid iodine has a bright metallic luster but is a non-metal and a poor conductor of electricity in the solid state. Under high pressure (above 16 GPa), iodine becomes metallic and conductive. Gaseous iodine strongly absorbs visible light, giving it its intense purple color. Iodine is poorly soluble in pure water (0.03 g/100 mL at 20 °C) but highly soluble in ethanol and in iodide solutions where it forms the triiodide ion I₃⁻.

Melting point of iodine: 386.85 K (113.7 °C).

Boiling point of iodine: 457.4 K (184.3 °C).

Iodine sublimes easily at room temperature, producing spectacular purple vapors.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine-123 — \(\,^{123}\mathrm{I}\,\) | 53 | 70 | 122.905589 u | Synthetic | ≈ 13.2 hours | Radioactive (EC). Used in SPECT medical imaging for the thyroid. |

| Iodine-125 — \(\,^{125}\mathrm{I}\,\) | 53 | 72 | 124.904624 u | Synthetic | ≈ 59.4 days | Radioactive (EC). Used in radiotherapy and as a tracer in molecular biology. |

| Iodine-127 — \(\,^{127}\mathrm{I}\,\) | 53 | 74 | 126.904473 u | ≈ 100 % | Stable | Only stable isotope of iodine, representing all natural iodine. |

| Iodine-129 — \(\,^{129}\mathrm{I}\,\) | 53 | 76 | 128.904988 u | Traces (fission product) | ≈ 15.7 million years | Radioactive (β⁻). Long-lived fission product, environmental tracer. |

| Iodine-131 — \(\,^{131}\mathrm{I}\,\) | 53 | 78 | 130.906125 u | Synthetic | ≈ 8.02 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Major fission product, used in nuclear thyroid medicine. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Iodine has 53 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁵, or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁵. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(7).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O shell (n=5): contains 7 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁵. These seven electrons are the valence electrons of iodine.

Iodine has 7 valence electrons: two 5s² electrons and five 5p⁵ electrons, lacking only one electron to reach the stable noble gas configuration of xenon. The main oxidation states are -1, +1, +3, +5, and +7. The -1 state is the most common, forming the iodide ion I⁻ in salts such as potassium iodide (KI) and sodium iodide (NaI).

The +1 state appears in compounds such as iodine monochloride (ICl). The +3 state exists in iodine trichloride (ICl₃). The +5 state is present in iodic acid (HIO₃) and iodates such as potassium iodate (KIO₃). The +7 state, the most oxidized, appears in periodic acid (HIO₄ or H₅IO₆) and periodates, where iodine uses all its valence electrons. Molecular iodine I₂ corresponds to the 0 oxidation state.

Iodine is the least reactive of the stable halogens (after fluorine, chlorine, and bromine), but remains a significant oxidant. At room temperature, iodine reacts slowly with many metals to form iodides. With alkali metals, the reaction can be vigorous: 2Na + I₂ → 2NaI. Sodium and potassium react violently with iodine, producing flames and fumes.

Iodine does not react directly with oxygen, but iodine oxides (I₂O₅, I₂O₄, I₄O₉) can be synthesized indirectly. With hydrogen, iodine forms hydrogen iodide (HI) in a reversible and incomplete reaction: H₂ + I₂ ⇌ 2HI. This equilibrium reaction is classic in chemical thermodynamics.

Iodine reacts with more reactive halogens to form interhalogens such as ICl, IBr, and IF₅. With chlorine, the reaction forms iodine chlorides: I₂ + Cl₂ → 2ICl or I₂ + 3Cl₂ → 2ICl₃. Iodine dissolves in iodide solutions to form the brown triiodide ion: I₂ + I⁻ → I₃⁻, greatly increasing its aqueous solubility.

The characteristic reaction for detecting iodine uses starch, which forms an intense blue-violet complex with molecular iodine, allowing the detection of minute traces of iodine (sensitivity on the order of micrograms). This reaction is used in analytical chemistry and iodometric titrimetry.

The most crucial application of iodine is its absolutely essential role in human health, particularly for thyroid function. Iodine is the fundamental constituent of the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which regulate metabolism, growth, neurological development, and many other essential physiological functions.

Iodine deficiency is the world's leading cause of preventable mental retardation and brain development disorders in children. Iodine deficiency disorders affect about 2 billion people worldwide, particularly in mountainous and inland regions far from the sea. Manifestations include goiter (thyroid enlargement), hypothyroidism, cretinism, and cognitive deficits.

Universal salt iodization, recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), is one of the most effective and cost-effective public health interventions ever implemented. Adding 15-40 mg of iodine per kilogram of salt (as potassium iodate or iodide) is sufficient to prevent deficiency disorders. This strategy has eliminated deficiency disorders in many developed countries.

An adult requires about 150 micrograms of iodine per day, while pregnant and breastfeeding women need 220-290 micrograms. Natural dietary sources include seafood (fish, shellfish, seaweed), dairy products, and eggs. A single dried kombu seaweed can contain several milligrams of iodine, far exceeding daily requirements.

Radioactive iodine, particularly the isotope ¹³¹I, plays a major role in nuclear medicine. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8 days and emits beta and gamma radiation, allowing both therapeutic treatment and diagnostic imaging. The thyroid gland selectively absorbs iodine, naturally concentrating administered radioactive iodine.

Radioactive iodine treatment is the standard therapy for hyperthyroidism (Graves' disease, toxic nodules) and differentiated thyroid cancer. A single oral dose of iodine-131 selectively destroys hyperactive or cancerous thyroid cells through internal irradiation, sparing surrounding tissues. For thyroid cancer, after surgical thyroidectomy, radioactive iodine eliminates residual cancer cells and metastases.

Iodine-123, with a shorter half-life of 13 hours and emitting only gamma rays, is used for diagnostic scintigraphic imaging of the thyroid without significant therapeutic effect. Iodine-125 is used in brachytherapy to treat localized tumors, particularly prostate cancers and ocular melanomas, as well as a tracer in biological research.

Iodine is a powerful broad-spectrum antiseptic and disinfectant, effective against bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and spores. Its bactericidal action results from the oxidation and iodination of microbial cellular components, particularly proteins and nucleic acids, causing rapid cell death.

Iodine tincture (alcoholic solution of iodine and potassium iodide) was the standard surgical antiseptic for over a century. Povidone-iodine (Betadine), a complex of iodine with polyvinylpyrrolidone, has become the modern reference antiseptic. It gradually releases active iodine, reducing irritation while maintaining prolonged antimicrobial efficacy.

10% povidone-iodine solutions contain 1% available iodine and are used for preoperative skin disinfection, wound treatment, and as an antiseptic gargle. Iodine tablets are used for emergency disinfection of drinking water in survival situations, natural disasters, or travel to developing countries.

Iodine has relatively low toxicity at nutritional doses but can become toxic at high doses. Acute iodine poisoning (ingestion of several grams) causes severe abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, burns to the mouth and throat, and potentially cardiovascular shock. The classic antidote is starch, which complexes iodine and reduces its absorption.

Chronic excessive exposure to iodine can paradoxically induce thyroid dysfunction, either hypothyroidism (Wolff-Chaikoff effect) or hyperthyroidism (Jod-Basedow phenomenon), particularly in individuals with pre-existing abnormal thyroid function. The tolerable upper limit is set at 1100 micrograms per day for adults.

Iodine vapors are highly irritating to the eyes, respiratory mucous membranes, and lungs. Occupational exposure in the chemical industry requires adequate ventilation and protective equipment. Elemental iodine intensely stains skin and tissues brown-yellow, but these stains are temporary and gradually fade.

Radioactive iodine, particularly ¹³¹I, is one of the main radiological risks during nuclear accidents. During the Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011) disasters, massive releases of iodine-131 caused a significant increase in thyroid cancers, particularly in children. The preventive distribution of potassium iodide tablets saturates the thyroid with stable iodine, blocking the uptake of radioactive iodine and reducing the risk of thyroid cancer.

Iodine is synthesized in stars mainly through the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during core-collapse supernovae and neutron star mergers (kilonova). the s-process (slow neutron capture) in AGB stars contributes minimally to iodine production. The stable isotope ¹²⁷I results mainly from the r-process.

The cosmic abundance of iodine is extremely low, about 9×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, placing it among the rarest elements in the universe. This rarity is explained by the odd number of protons (I, Z = 53) of iodine, making it less stable than elements with an even number of protons, and by its limited production in rare explosive events.

The radioactive isotope ¹²⁹I, with a half-life of 15.7 million years, is produced by the r-process and by spontaneous fission of uranium-238. The presence of ¹²⁹I in primitive meteorites indicates that this isotope was present in the early solar system, providing constraints on the time between the last stellar nucleosynthesis and the formation of the solar system, estimated at a few tens of millions of years. The ¹²⁹I/¹²⁷I ratio in meteorites is used as a radioactive chronometer to date events in the early solar system.

Spectral lines of neutral iodine (I I) and ionized iodine (I II) are rarely observed in stellar spectra due to the very low cosmic abundance of this element and its relatively high first ionization potential. Nevertheless, traces of iodine have been detected in a few chemically peculiar stars enriched in r-process elements, confirming models of explosive nucleosynthesis. The observation of iodine in the spectra of kilonovae (neutron star mergers) confirms that these cataclysmic events are the main sites of production of heavy r-process elements, including iodine.

Global iodine production is geographically concentrated, with Chile and Japan together accounting for about 80-85% of total production. Chile extracts iodine mainly from caliche (natural nitrate) brines in the Atacama Desert, the world's richest iodine region. These deposits were formed by the evaporation of ancient seawater enriched in iodine by algae.

Japan recovers iodine from natural gas extraction brines, particularly in the Chiba region. These underground brines contain high concentrations of iodine (50-150 mg/L) due to the dissolution of ancient marine organic matter. The United States and Turkmenistan also produce iodine from oilfield brines.

The extraction process generally involves oxidizing iodide (I⁻) to molecular iodine (I₂) with chlorine gas or other oxidants, followed by purification by sublimation. The iodine produced is typically over 99.5% pure. Global demand for iodine grows by about 3-5% annually, driven mainly by public health applications, medical contrast agents, and industrial uses.

Recycling of iodine from industrial and pharmaceutical sources remains limited, although it is increasing. Iodine recovered from photographic solutions was historically significant, but this source has largely disappeared with the decline of silver photography. Concerns about long-term supply security have led some countries to establish strategic iodine reserves to ensure public health needs.

Iodine follows a complex biogeochemical cycle between the oceans, atmosphere, soils, and living organisms. The oceans are the main reservoir of iodine on Earth, containing about 60 billion tons of dissolved iodine. Seaweed massively concentrates iodine, reaching concentration factors of 10,000 to 30,000 times that of seawater.

Kelp (laminaria) releases volatile organic iodine compounds such as iodomethane (CH₃I) and diiodomethane (CH₂I₂) into the atmosphere, significantly contributing to the transport of iodine to the continents. These biogenic emissions represent about 1-2 million tons of iodine per year in the form of volatile organic compounds. These compounds also participate in atmospheric chemistry, influencing aerosol and cloud formation.

On continents, iodine is generally deficient in soils, particularly in mountainous, glacial, and inland regions far from the sea where atmospheric deposits are low. Leaching by precipitation gradually depletes soils of iodine. Coastal areas receive greater atmospheric inputs of marine iodine, reducing deficiencies.

Plants absorb iodine from the soil mainly in the form of iodate (IO₃⁻) and iodide (I⁻), but concentrations are generally low, insufficient to meet human needs except in coastal regions or for seafood products. This natural iodine deficiency in many terrestrial ecosystems explains the importance of food fortification and salt iodization.