Vanadium has a turbulent history marked by several successive discoveries. In 1801, the Mexican mineralogist Andrés Manuel del Río (1764–1849) discovered a new element in a lead ore from Mexico and named it erythronium, referring to the red colors of its salts. However, mistakenly convinced by other chemists that it was merely impure chromium, del Río abandoned his discovery. It was not until 1830 that the Swedish chemist Nils Gabriel Sefström (1787–1845) independently rediscovered this element in a Swedish iron ore and named it vanadium, in honor of Vanadis, the goddess of beauty in Norse mythology, due to the variety and beauty of the colors of its compounds. In the same year, Friedrich Wöhler (1800–1882) confirmed that del Río's erythronium was indeed vanadium. Pure metallic vanadium was not isolated until 1867 by Henry Enfield Roscoe (1833–1915) through the reduction of vanadium chloride with hydrogen.

Vanadium (symbol V, atomic number 23) is a transition metal in group 5 of the periodic table. Its atom has 23 protons, usually 28 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{51}\mathrm{V}\)), and 23 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d³ 4s².

At room temperature, vanadium is a silvery-gray solid metal with a bright luster, moderately dense (density ≈ 6.11 g/cm³). It has excellent mechanical strength and remarkable hardness. Pure vanadium resists corrosion well due to the formation of a protective oxide layer on its surface. Melting point of vanadium (liquid state): 2,183 K (1,910 °C). Boiling point of vanadium (gaseous state): 3,680 K (3,407 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanadium-50 — \(\,^{50}\mathrm{V}\,\) | 23 | 27 | 49.947159 u | ≈ 0.250 % | ≈ 1.4 × 10¹⁷ years | Radioactive with a very long half-life, β⁺ decay to \(\,^{50}\mathrm{Ti}\) or β⁻ decay to \(\,^{50}\mathrm{Cr}\). Considered quasi-stable. |

| Vanadium-51 — \(\,^{51}\mathrm{V}\,\) | 23 | 28 | 50.943960 u | ≈ 99.750 % | Stable | Dominant isotope of vanadium; has a nuclear magnetic moment used in NMR. |

| Vanadium-48 — \(\,^{48}\mathrm{V}\,\) | 23 | 25 | 47.952254 u | Synthetic | ≈ 15.97 days | Radioactive, electron capture to \(\,^{48}\mathrm{Ti}\). Used in medical research and imaging. |

| Vanadium-49 — \(\,^{49}\mathrm{V}\,\) | 23 | 26 | 48.948516 u | Synthetic | ≈ 330 days | Radioactive, electron capture to \(\,^{49}\mathrm{Ti}\). Used as a tracer in materials science. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

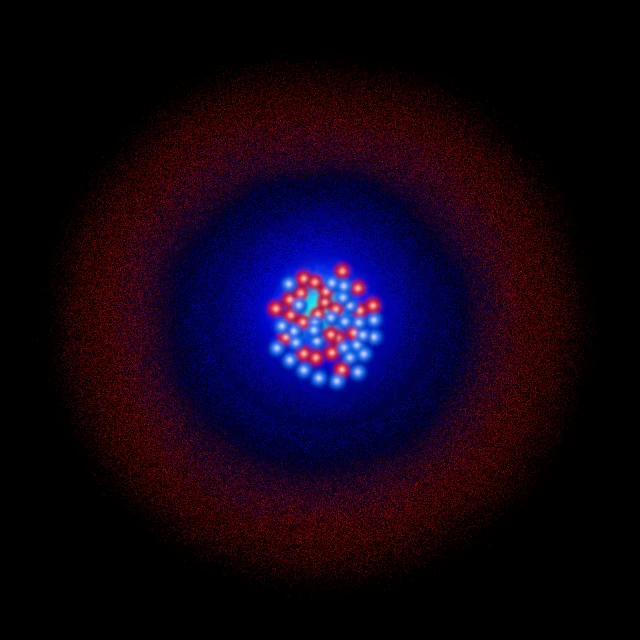

Vanadium has 23 electrons distributed across four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d³ 4s², or simplified: [Ar] 3d³ 4s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(11) N(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 11 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d³. The 3s and 3p orbitals are complete, while the 3d orbitals contain only 3 out of 10 possible electrons.

N shell (n=4): contains 2 electrons in the 4s subshell. These electrons are the first to be involved in chemical bonding.

The 5 electrons in the outer shells (3d³ 4s²) are the valence electrons of vanadium. This configuration explains its particularly rich chemistry:

By losing the 2 4s electrons, vanadium forms the V²⁺ ion (oxidation state +2), producing purple compounds.

By losing the 2 4s electrons and 1 3d electron, it forms the V³⁺ ion (oxidation state +3), producing green solutions.

By losing 4 electrons, it forms the V⁴⁺ ion (oxidation state +4), producing blue compounds.

By losing all its valence electrons (4s² 3d³), it forms the V⁵⁺ ion (oxidation state +5), the most stable state, producing yellow compounds.

The electronic configuration of vanadium, with its partially filled 3d orbitals, gives it characteristic properties of transition metals: formation of varied colored compounds, significant catalytic activity, and the ability to exist in multiple oxidation states. This chemical versatility makes vanadium particularly interesting for catalytic and electrochemical applications.

Pure vanadium is relatively stable at room temperature due to a protective oxide layer. At high temperatures, it reacts with oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, and halogens. Vanadium exhibits extremely rich chemistry with five stable oxidation states (from +2 to +5), each characterized by a distinctive color in aqueous solution. Vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) is the most industrially important compound, used notably as a catalyst in the production of sulfuric acid. Vanadium resists seawater, saline solutions, and dilute acids, but can be attacked by hydrofluoric acid, concentrated nitric acid, and hot alkaline bases.

Vanadium is mainly produced in massive stars during advanced stages of nuclear fusion, particularly during silicon burning that precedes supernova explosions. It is also synthesized during supernova explosions via the rapid neutron capture process (r-process). The abundance of vanadium in stars and meteorites provides valuable information about the history of galactic nucleosynthesis and the chemical evolution of the universe.

Spectral lines of vanadium (V I, V II) are observed in stellar spectra and allow the determination of chemical composition, temperature, and surface gravity of stars. In solar-type stars, vanadium is produced gradually during their evolution. The study of the vanadium/iron ratio in ancient stars helps astrophysicists understand the early stages of chemical enrichment in our galaxy and reconstruct the history of successive stellar generations. Vanadium also plays a role in characterizing brown dwarfs and giant gaseous exoplanets, where it can exist in gaseous form in hot atmospheres.

N.B.:

Vanadium is relatively abundant in the Earth's crust (about 0.019% by mass), ranking it as the 20th most abundant element. It never exists in its native state but is found combined in more than 65 different minerals, including vanadinite [Pb₅(VO₄)₃Cl], patronite (VS₄), and carnotite [K₂(UO₂)₂(VO₄)₂·3H₂O]. The main industrial source of vanadium comes from titaniferous magnetite slag and petroleum refining residues. China, Russia, and South Africa are the world's leading producers. Vanadium is considered a strategic metal due to its growing importance in energy storage technologies and high-performance steel metallurgy.