Selenium was discovered in 1817 by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779-1848) and his assistant Johan Gottlieb Gahn. Berzelius was working in a sulfuric acid factory in Gripsholm, Sweden, where he was studying a reddish deposit that accumulated at the bottom of the lead chambers used for acid production. This residue was initially thought to be tellurium, an element discovered a few years earlier.

Upon carefully analyzing this deposit, Berzelius noticed significant differences from tellurium. After a series of chemical experiments, he succeeded in isolating a new element, which he named selenium, from the Greek selene, meaning moon, in analogy with tellurium, whose name derives from tellus (Earth). This naming reflected the relationship between these two chemically similar elements.

Berzelius' discovery of selenium was a major contribution to 19th-century chemistry. Berzelius was already famous for discovering several other elements, including cerium, thorium, and silicon, and for developing the modern chemical notation using alphabetical symbols.

In 1873, the British electrician Willoughby Smith discovered that the electrical conductivity of selenium increased significantly under the effect of light. This revolutionary photoelectric property paved the way for many technological applications and made selenium one of the first materials used in photocells, photographic exposure meters, and early mechanical television systems.

Selenium (symbol Se, atomic number 34) is a non-metal of group 16 of the periodic table, belonging to the chalcogen family with oxygen, sulfur, tellurium, and polonium. Its atom has 34 protons, usually 46 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{80}\mathrm{Se}\)) and 34 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁴.

Selenium exhibits several allotropic forms with very different physical properties. The most stable form is gray selenium (metallic selenium or hexagonal selenium), a shiny gray metallic solid with a hexagonal crystalline structure. This form has a density of 4.81 g/cm³ and remarkable semiconductor properties, with conductivity increasing by a factor of 1000 under the effect of light.

Red selenium exists in two distinct allotropic forms: red selenium α (monoclinic) and red selenium β (monoclinic), both composed of cyclic Se₈ molecules. These red forms are obtained by rapid cooling of molten selenium or by precipitation from solutions. They are unstable and slowly transform into gray selenium at room temperature.

Amorphous selenium (or black vitreous selenium) is obtained by very rapid cooling of liquid selenium. This black vitreous form has a disordered structure and also transforms into gray selenium when heated above 180 °C. This form was historically used in rectifiers and photocells.

Selenium melts at 221 °C (494 K) and boils at 685 °C (958 K). The liquid obtained during melting is initially reddish-brown and gradually turns black due to polymerization. The viscosity of liquid selenium also increases dramatically with temperature due to the formation of long molecular chains.

Melting point of selenium: 494 K (221 °C).

Boiling point of selenium: 958 K (685 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium-74 — \(\,^{74}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 40 | 73.922476 u | ≈ 0.89 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope of natural selenium. |

| Selenium-76 — \(\,^{76}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 42 | 75.919214 u | ≈ 9.37 % | Stable | Stable isotope used as a tracer in biology. |

| Selenium-77 — \(\,^{77}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 43 | 76.919914 u | ≈ 7.63 % | Stable | Has a nuclear spin used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Selenium-78 — \(\,^{78}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 44 | 77.917309 u | ≈ 23.77 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope of natural selenium. |

| Selenium-80 — \(\,^{80}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 46 | 79.916521 u | ≈ 49.61 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of selenium, representing nearly half of natural selenium. |

| Selenium-82 — \(\,^{82}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 48 | 81.916699 u | ≈ 8.73 % | ≈ 1.08 × 10²⁰ years | Radioactive (β⁻β⁻). Extremely slow double beta decay, considered quasi-stable. |

| Selenium-75 — \(\,^{75}\mathrm{Se}\,\) | 34 | 41 | 74.922523 u | Synthetic | ≈ 119.8 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Gamma emitter used in industrial radiography and medicine. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

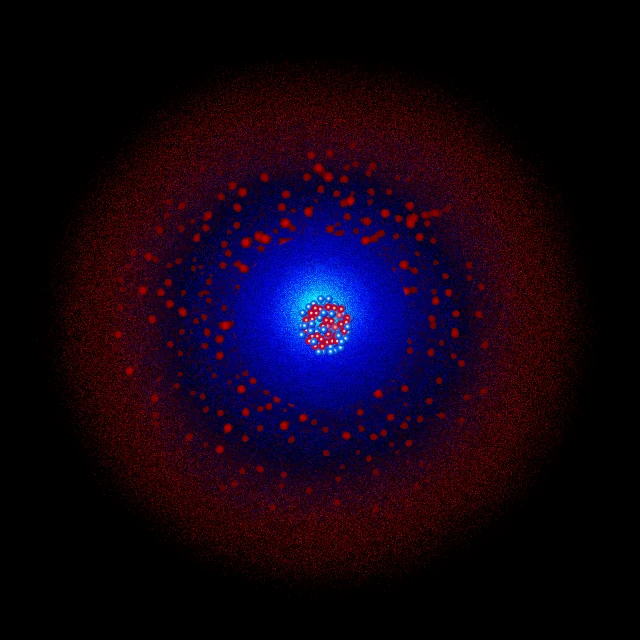

Selenium has 34 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁴, or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁴. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(6).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. The presence of the complete 3d subshell is characteristic of post-transition elements and significantly influences the properties of selenium.

N Shell (n=4): contains 6 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁴. These six electrons are the valence electrons of selenium.

The 6 electrons in the outer shell (4s² 4p⁴) are the valence electrons of selenium. This configuration explains its great chemical diversity:

The most common oxidation state of selenium is -2, where it gains two electrons to complete its valence shell, forming the selenide ion Se²⁻ with the configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶, isoelectronic with krypton. Metallic selenides such as Na₂Se or ZnSe are important in chemistry and technology.

The oxidation state +4 is also very important, particularly in selenium dioxide (SeO₂), an amphoteric compound widely used in organic synthesis. In this state, selenium uses four of its valence electrons to form bonds.

The oxidation state +6 appears in the most oxidized compounds such as selenic acid (H₂SeO₄) and selenium trioxide (SeO₃). These compounds are powerful oxidants, where selenium uses all its available valence electrons.

Intermediate oxidation states also exist: +2 in selenium dichloride (SeCl₂) and -1 in organic diselenides (R-Se-Se-R). The state 0 corresponds to elemental selenium in its various allotropic forms.

The chemistry of selenium shows many similarities with that of sulfur, its lighter homologue in group 16, although selenium is generally less electronegative and forms longer and weaker bonds. This difference manifests itself in greater polarizability and a better ability to form compounds with transition metals.

Gray selenium is relatively stable in air at room temperature, oxidizing only slowly. However, when heated in air, it burns with a characteristic blue flame, forming selenium dioxide (SeO₂), which is released as white smoke with a pungent odor of rotten radishes: Se + O₂ → SeO₂. This distinctive odor is due to volatile selenium compounds.

Selenium reacts with hydrogen at high temperature to form hydrogen selenide (H₂Se), an extremely toxic and foul-smelling gas, more toxic than hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). H₂Se is unstable and easily decomposes into hydrogen and elemental selenium.

With oxidizing acids, selenium reacts to form selenious acid (H₂SeO₃) or selenic acid (H₂SeO₄) depending on the conditions. Hot concentrated nitric acid oxidizes selenium: 3Se + 4HNO₃ + H₂O → 3H₂SeO₃ + 4NO. Selenium is resistant to dilute non-oxidizing acids.

Selenium dissolved in alkaline solutions forms selenites (SeO₃²⁻) and selenides (Se²⁻) depending on the conditions: 3Se + 6OH⁻ → 2Se²⁻ + SeO₃²⁻ + 3H₂O. This disproportionation reaction is characteristic of chalcogens in basic medium.

Selenium reacts directly with all halogens to form various halides: Se + X₂ → SeX₂ or SeX₄ (where X = F, Cl, Br, I). Selenium tetrafluoride (SeF₄) and selenium hexafluoride (SeF₆) are particularly stable. Selenium dichloride (SeCl₂) and tetrachloride (SeCl₄) are liquids used as reagents.

Selenium easily forms organoselenium compounds, analogous to sulfur compounds but generally more reactive. Organic selenides, selenols (R-SeH), selenides (R-Se-R'), and organic selenic acids play an important role in organic chemistry and biochemistry. Some essential amino acids contain selenium, notably selenocysteine and selenomethionine.

Selenium is an essential trace element for human and animal health. It plays a crucial role in the functioning of several antioxidant enzymes, notably glutathione peroxidases (GPx) and thioredoxin reductases (TrxR), which protect cells against oxidative damage caused by free radicals.

Selenium is incorporated into proteins in the form of selenocysteine, sometimes called the 21st amino acid. This incorporation requires specialized cellular machinery that recognizes a specific codon (UGA), normally used as a stop signal for translation. About 25 selenoproteins have been identified in humans.

The daily selenium requirement for an adult is about 55 micrograms per day. Selenium deficiency can lead to heart disorders (Keshan disease), thyroid disorders, and weakened immunity. Keshan disease, discovered in the 1930s in China, is a cardiomyopathy caused by severe selenium deficiency in the soils of certain regions.

However, selenium has a narrow therapeutic window between beneficial and toxic doses. Excessive selenium intake (beyond 400 micrograms per day) can cause selenosis, characterized by hair and nail loss, gastrointestinal disorders, neurological problems, and a characteristic garlic odor on the breath due to the elimination of methylated selenium compounds.

The main dietary sources of selenium include Brazil nuts (exceptionally rich in selenium), seafood, offal, meats, whole grains, and eggs. The selenium content of plant foods depends heavily on the selenium concentration of the soils where they were grown.

Selenium is synthesized in stars through several stellar nucleosynthesis processes. Selenium isotopes are mainly produced by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, as well as by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during cataclysmic events such as type II supernovae or neutron star mergers.

The distribution of the six stable selenium isotopes (\(\,^{74}\mathrm{Se}\), \(\,^{76}\mathrm{Se}\), \(\,^{77}\mathrm{Se}\), \(\,^{78}\mathrm{Se}\), \(\,^{80}\mathrm{Se}\), \(\,^{82}\mathrm{Se}\)) reflects the different contributions of the s and r processes to nucleosynthesis. The study of selenium isotopic ratios in primitive meteorites provides valuable information on the formation conditions of the solar system and the relative contribution of different nucleosynthesis processes.

The cosmic abundance of selenium is relatively low, about 3×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This rarity is explained by the difficulties in synthesizing nuclei in this atomic mass region (A ≈ 75-82) and by the fact that selenium lies in a region of moderate nuclear stability.

Spectral lines of ionized selenium (Se II, Se III) have been detected in the spectra of certain hot stars and peculiar stellar objects. The observation of these lines allows the study of stellar chemical enrichment and the chemical evolution of galaxies over cosmic time.

Selenium also plays an interesting role in the study of isotopic anomalies in meteorites. Certain calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions (CAIs) show excesses of selenium-82, suggesting the contribution of presolar grains formed in specific stellar environments before the formation of the solar system.

N.B. :

Selenium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.00005% by mass (0.5 ppm), making it a relatively rare element, comparable to mercury. It generally does not form its own minerals but is found associated with other elements, mainly in metal sulfides of copper, lead, nickel, and silver. The main selenium-bearing minerals are clausthalite (PbSe), tiemannite (HgSe), and naumannite (Ag₂Se).

Selenium is mainly extracted as a byproduct of the electrolytic refining of copper, where it accumulates in the anode slime. Another important source is the processing of lead and zinc ores. Global selenium production is about 2,500 tons per year, mainly in Japan (≈ 40%), Belgium, Germany, Canada, and Russia.

The distribution of selenium in terrestrial soils is very uneven. Some regions, such as the Great Plains in the United States, have selenium-rich soils, while others, such as certain Chinese provinces, have severe selenium deficiencies. This geographical disparity has significant implications for public health and agriculture.

The recycling of selenium is becoming increasingly important with the growth of electronics and photovoltaic energy. Selenium can be recovered from used photocopiers, end-of-life solar panels, and industrial processes. The current recycling rate is estimated at about 30% of total production, significantly higher than that of many other rare elements.

Global demand for selenium is steadily increasing, mainly driven by the photovoltaic solar energy sector, metallurgy, and dietary supplements. Selenium is considered a strategic element by several countries due to its importance in green technologies and the geographical concentration of its production.