Thorium, like other heavy actinides, is mainly formed during extreme astrophysical events, particularly the r-process (rapid neutron capture process) that occurs during neutron star mergers or certain supernovae. In the solar system, it is present today due to its very long half-life. The isotope \(\,^{232}\mathrm{Th}\) (half-life of 14.05 billion years) serves as a cosmic chronometer in geochemistry and astrophysics. The thorium/uranium (Th/U) ratio and the thorium/other heavy elements ratio allow dating the age of the Earth's crust, meteorites, and estimating the age of our galaxy. Unlike short-lived radioactive elements, thorium-232 produces a constant and long-lasting heat flow in rocky planets, contributing to the maintenance of internal geological activity over geological time scales.

Thorium was discovered in 1828 by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779-1848). He isolated it from a sample of a blackish rock known as thorite (a thorium silicate) that had been sent to him by a Norwegian pastor and amateur mineralogist, Reverend Hans Morten Thrane Esmark. Berzelius named the new element "thorium" in honor of Thor, the god of thunder in Norse mythology. For nearly a century, thorium remained mainly a laboratory curiosity and found limited applications in the incandescent mantles of gas lamps (Thorite). The true importance of thorium as a fertile element in the nuclear fuel cycle was only realized with the discovery of radioactivity and nuclear fission. In 1941, Glenn T. Seaborg and his colleagues identified the first fissile isotope derived from thorium, uranium-233 (\(\,^{233}\mathrm{U}\)), paving the way for the concept of the thorium cycle.

N.B.:

Thorium has long been the "forgotten star" of nuclear energy. While 20th-century nuclear programs focused massively on uranium and plutonium for military (bombs) and civilian reasons, thorium, deemed less suitable for producing fissile materials for weapons, was largely neglected. It was only with the rise of concerns about proliferation, long-lived nuclear waste, and the depletion of uranium reserves that thorium experienced a global resurgence of interest in the 21st century as a potential fuel for safer and more sustainable nuclear reactors.

Thorium (symbol Th, atomic number 90) is an actinide, the second element in the series after actinium. It is generally considered a fertile metal rather than fissile. Its main and almost unique natural isotope is \(\,^{232}\mathrm{Th}\), an alpha emitter with a very long half-life (14.05 billion years). Pure thorium metal is silvery-gray, soft, malleable, and ductile. At room temperature, it has a face-centered cubic crystal structure. It is relatively stable in air, developing a thin protective oxide layer (ThO₂, thoria), much more stable than that of uranium. Its density is 11.7 g/cm³. It is a good electrical conductor.

Melting point: 2023 K (1750 °C).

Boiling point: 5061 K (4788 °C).

Thorium is about three to four times more abundant in the Earth's crust than uranium.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Main decay mode / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thorium-232 — \(\,^{232}\mathrm{Th}\,\) | 90 | 142 | 232.038055 u | ~100 % | 14.05 billion years | α (100%). Primordial fertile isotope. Captures a neutron to start the chain leading to fissile uranium-233. Source of geological heat. |

| Thorium-228 — \(\,^{228}\mathrm{Th}\) | 90 | 138 | 228.028741 u | Trace (decay product) | 1.913 year | α (100%). Daughter of radium-228 in the thorium-232 decay chain. Used as a tracer in oceanography and geochemistry. |

| Thorium-230 — \(\,^{230}\mathrm{Th}\) | 90 | 140 | 230.033134 u | Not natural (decay product) | 75,380 years | α (100%). Also called ionium. Daughter of uranium-238. Crucial dating tool (uranium series) for carbonates, corals, and marine sediments. |

| Thorium-229 — \(\,^{229}\mathrm{Th}\) | 90 | 139 | 229.031762 u | Not natural (synthetic) | 7,917 years | α (100%). Known for its nuclear isomeric level of the lowest energy ever measured (~8 eV), paving the way for a nuclear clock of very high precision. |

N.B.:

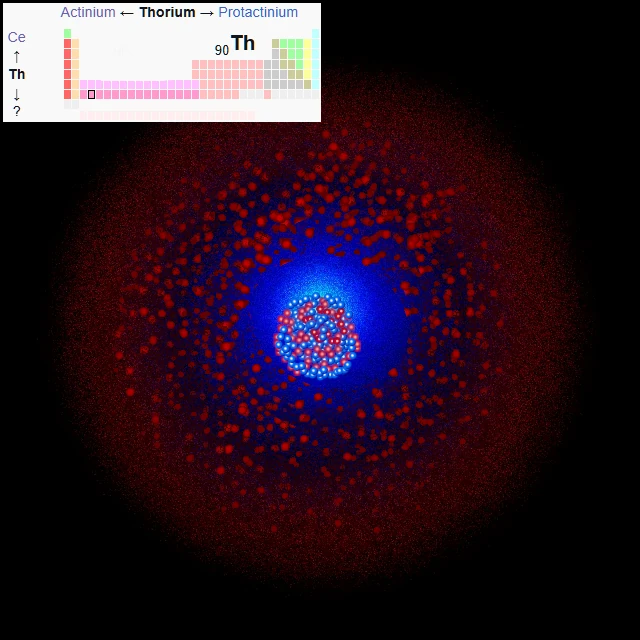

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Thorium has 90 electrons. Its ground state electronic configuration is [Rn] 6d2 7s2. Unlike uranium and subsequent actinides, it has no 5f electrons in its ground state. This configuration makes it chemically similar to hafnium (group 4) and, to a lesser extent, cerium. It mainly exhibits the +4 oxidation state (Th4+), which is extremely stable. The Th4+ ion is relatively large and highly charged, making it a strong Lewis acid and allowing it to form stable complexes with a wide variety of ligands (carbonates, phosphates, organics). Thorium practically does not exhibit a +3 oxidation state in aqueous solution, unlike most other light actinides.

Thorium metal is quite reactive. It oxidizes slowly in air and burns to form thoria (ThO₂), an extremely refractory white ceramic (melting point ~3390 °C). It reacts with halogens, hydrogen, nitrogen, carbon, and sulfur at high temperatures. In solution, Th4+ is the only stable ion. It hydrolyzes easily and precipitates as Th(OH)₄ hydroxide at neutral or basic pH. Thorium oxide ThO₂ and nitrate Th(NO₃)₄ are its most important industrial compounds. The nitrate is highly soluble in water and organic solvents, which is crucial for thorium fuel extraction and reprocessing processes.

Thorium is a relatively abundant element in the Earth's crust, with an average concentration estimated at about 9.6 ppm, three to four times that of uranium. It does not occur in native metallic form. Its main ore is monazite, a rare earth phosphate that typically contains 3% to 12% thorium oxide (ThO₂). Other minerals include thorite and thorianite. The main reserves are located in India (which has the world's largest reserves), Brazil, Australia, the United States, and Norway. Thorium extraction is generally a by-product of rare earth or titanium mining. Currently, there is no significant global market for thorium as a nuclear fuel, so its production is limited and linked to demand for its other applications (refractories, alloys). Its price is mainly determined by the costs of separation and purification from rare earth ores.

Natural thorium (almost exclusively Th-232) is a low specific activity radioelement due to its very long half-life. Its external radiation (mainly alpha particles and weak gamma radiation from its descendants) is easily stopped by a sheet of paper or the dead layer of skin. The main risk is internal: if inhaled or ingested as dust or aerosols, thorium can deposit in the lungs, bones, and organs, where it remains for decades, irradiating neighboring tissues. It is a recognized chemical and radiological carcinogen. Handling thorium powders or freshly separated thorium (containing few of its short-lived descendants) requires standard powder chemistry precautions (fume hood). Long-term storage of large quantities requires controlled ventilation to prevent the accumulation of radon-220 (thoron), a very short-lived radioactive gas (55.6 s) in the thorium decay chain.