Technetium holds a unique place in the history of chemistry as the first entirely artificial element synthesized by humanity. For decades, element 43 remained elusive, leaving a gap in Mendeleev's periodic table between molybdenum (42) and ruthenium (44). Many chemists claimed to have discovered it, proposing names like masurium or lucium, but none of these claims could be confirmed.

The true discovery occurred in 1937 when Italian physicists Carlo Perrier (1886-1948) and Emilio Segrè (1905-1989) analyzed a molybdenum foil irradiated with deuterons in the cyclotron at Berkeley, California. Ernest Lawrence, inventor of the cyclotron and future Nobel Prize winner in physics, had sent them this sample. Perrier and Segrè succeeded in isolating and identifying element 43, thus solving the mystery of the missing element.

The name technetium was chosen in 1947 by Perrier and Segrè, derived from the Greek technetos, meaning artificial, highlighting its unique nature as an element that does not exist naturally on Earth in detectable quantities. This discovery marked a turning point in the understanding of nuclear stability and ushered in the era of transuranic and synthetic elements.

It is now established that technetium does not exist naturally on Earth because all its isotopes are radioactive, with the most stable isotope (technetium-98) having a half-life of only 4.2 million years. This period is far too short on a geological scale: all the technetium present during the formation of the Earth 4.5 billion years ago has long since decayed. However, technetium does exist naturally in the universe, continuously synthesized in stars.

Technetium (symbol Tc, atomic number 43) is a transition metal in group 7 of the periodic table. Its atom has 43 protons and 43 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s². The number of neutrons varies depending on the isotope, as technetium has no stable isotopes.

Metallic technetium is a silvery-gray metal with an appearance similar to platinum. It has a density of 11.5 g/cm³, making it relatively heavy. Technetium crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure at room temperature. It is a slightly paramagnetic metal, a rare property for a transition metal.

Technetium melts at 2157 °C (2430 K) and boils at 4265 °C (4538 K). These high temperatures classify it among refractory metals. Technetium is a superconductor with a critical temperature of 7.8 K (-265.35 °C), a relatively high temperature for a pure metallic element.

All isotopes of technetium are radioactive. The most stable isotope, technetium-98, has a half-life of 4.2 million years. Technetium-99, a major fission product, has a half-life of 211,000 years. The medical isotope technetium-99m (metastable state) has a half-life of only 6.01 hours, ideal for diagnostic imaging.

Melting point of technetium: 2430 K (2157 °C).

Boiling point of technetium: 4538 K (4265 °C).

Technetium is the lightest element with no stable isotope.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technetium-97 — \(\,^{97}\mathrm{Tc}\,\) | 43 | 54 | 96.906365 u | Synthetic | ≈ 4.21 × 10⁶ years | Radioactive (electron capture). Isotope with the longest half-life after Tc-98. |

| Technetium-98 — \(\,^{98}\mathrm{Tc}\,\) | 43 | 55 | 97.907216 u | Synthetic | ≈ 4.2 × 10⁶ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Most stable isotope of technetium, but short half-life on a geological scale. |

| Technetium-99 — \(\,^{99}\mathrm{Tc}\,\) | 43 | 56 | 98.906255 u | Synthetic | ≈ 2.111 × 10⁵ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Major fission product. Long-lived nuclear waste problem. |

| Technetium-99m — \(\,^{99m}\mathrm{Tc}\,\) | 43 | 56 | 98.906254 u | Synthetic | ≈ 6.01 hours | Radioactive (isomeric transition, γ). Metastable state of Tc-99. Most used radioisotope in nuclear medicine. |

| Technetium-95m — \(\,^{95m}\mathrm{Tc}\,\) | 43 | 52 | 94.907657 u | Synthetic | ≈ 61 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Used in medical research and as a tracer. |

N.B.:

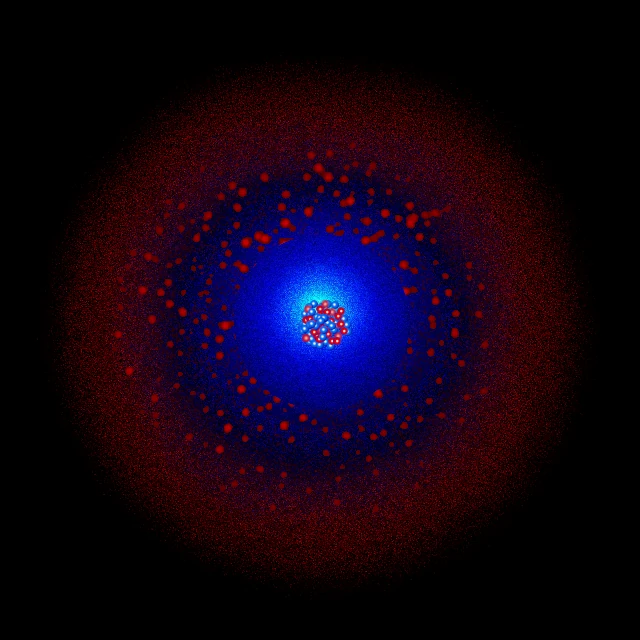

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Technetium has 43 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁵ 5s², or simplified: [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(13) O(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 13 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁵. The five 4d electrons are valence electrons.

O shell (n=5): contains 2 electrons in the 5s subshell. These electrons are also valence electrons.

Technetium has 7 valence electrons: five 4d⁵ electrons and two 5s² electrons. The configuration [Kr] 4d⁵ 5s² with the half-filled 4d subshell is stable. Technetium exhibits a wide range of oxidation states from -1 to +7, although states +4, +5, +6, and +7 are the most common.

The +7 oxidation state appears in pertechnetate (TcO₄⁻), the most stable and common ion of technetium in aqueous solution. The +4 state is present in technetium dioxide (TcO₂) and in many complexes used in nuclear medicine. The variable oxidation states of technetium allow it to form a rich and complex chemistry, particularly useful for medical applications.

Metallic technetium is relatively resistant to oxidation at room temperature due to a thin protective oxide layer. It only tarnishes slowly in humid air. However, at high temperatures (above 400 °C), technetium burns in oxygen to form technetium heptoxide (Tc₂O₇), a volatile yellow compound: 4Tc + 7O₂ → 2Tc₂O₇.

Technetium dissolves in nitric acid, aqua regia, and concentrated sulfuric acid to form pertechnetate ion (TcO₄⁻) solutions, but resists hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids. In solution, pertechnetate is remarkably chemically stable and does not precipitate easily, posing challenges for the management of nuclear waste containing technetium-99.

Technetium forms compounds with almost all non-metals. With halogens, it forms various halides (TcF₆, TcCl₄, TcBr₄). With sulfur, it forms sulfides, and technetium disulfide (TcS₂) has a structure similar to molybdenum disulfide. Technetium also forms a rich organometallic chemistry with carbonyl, phosphine, and other organic ligands.

Technetium-99m (Tc-99m) is the most important radioisotope in modern nuclear medicine, used in over 40 million diagnostic imaging procedures each year worldwide, accounting for about 80% of all nuclear medicine examinations. Its properties are almost ideal for medical imaging.

Tc-99m has a half-life of 6.01 hours, long enough to allow preparation, transport, and administration of radiopharmaceuticals, but short enough to minimize radiation exposure to the patient. It emits 140 keV gamma rays, an optimal energy for detection by gamma cameras while easily penetrating tissues. Above all, Tc-99m decays by pure isomeric transition, without emitting β particles that would cause tissue damage.

Tc-99m is produced from molybdenum-99 (Mo-99, half-life 66 hours) in technetium generators, commonly called "molybdenum cows." These generators contain Mo-99 adsorbed on an alumina column. Mo-99 continuously decays into Tc-99m, which can be eluted from the column with a saline solution. A generator can be used for about a week before the activity of Mo-99 becomes too low.

Tc-99m is incorporated into various radiopharmaceuticals targeting different organs and physiological processes: bone scintigraphy (detection of fractures, metastases), cardiac scintigraphy (myocardial perfusion), cerebral, renal, pulmonary, thyroid, and liver scintigraphy. The versatile chemistry of technetium allows the synthesis of specific complexes for each application.

Technetium-99 (Tc-99), a long-lived isotope (211,000 years), is one of the most problematic fission products in nuclear waste. It is produced with a high fission yield (about 6%) during the fission of uranium-235 and plutonium-239. Each ton of spent nuclear fuel contains about 0.5 to 1 kg of Tc-99.

Managing Tc-99 in nuclear waste is particularly difficult. The pertechnetate ion (TcO₄⁻), the stable chemical form of Tc-99 in solution, is highly soluble and mobile in the environment. It does not adsorb onto soils and can migrate long distances in groundwater, posing a long-term contamination risk. Low-energy β-emitting Tc-99 accumulates in the food chain, particularly in seafood.

Several strategies are being studied to immobilize Tc-99 in nuclear waste: incorporation into borosilicate glasses, synthesis of insoluble technetium compounds, and nuclear transmutation of Tc-99 into stable ruthenium-100 by neutron irradiation. Separation and transmutation of technetium could significantly reduce the long-term radiotoxicity of nuclear waste.

Although technetium does not exist naturally on Earth, it is continuously synthesized in certain stars by the s-process (slow neutron capture). The spectroscopic detection of technetium in the atmospheres of S-type stars and some carbon stars in 1952 by Paul Merrill was a major discovery in astrophysics, providing the first direct evidence that nucleosynthesis occurs actively in stars.

The presence of technetium in a star necessarily indicates recent nucleosynthesis (on an astronomical scale), as even the most stable isotope (Tc-98, half-life 4.2 million years) decays rapidly compared to the age of stars. The observed technetium must therefore have been recently synthesized in the star itself and transported to its surface by convection processes.

Stars showing technetium lines are typically asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, where the s-process actively produces heavy elements in a helium-burning shell. The detection of technetium confirms that these stars are the main sites of the s-process and enrich the interstellar medium with heavy elements via their powerful stellar winds.

N.B.:

Technetium does not exist naturally on Earth in measurable quantities. All technetium used is produced artificially. Molybdenum-99, the precursor to medical technetium-99m, is produced by the fission of uranium-235 in specialized nuclear reactors. Only five reactors in the world produce the majority of the world's Mo-99, creating a vulnerable supply situation.

Global production of Mo-99 is about 12,000 TBq (terabecquerels) per week. The main producers are located in the Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, South Africa, and Australia. The aging of these reactors and scheduled closures create a potential supply crisis for global nuclear medicine, stimulating research into alternative production methods (particle accelerators, fast flux reactors).

Pure metallic technetium is produced in tiny quantities for research, mainly by reducing technetium compounds with hydrogen at high temperatures. Due to its radioactivity and rarity, metallic technetium has no significant commercial applications. All technetium produced is intended for nuclear medicine as Tc-99m or is an unwanted nuclear waste in the form of Tc-99.