Xenon is a rare element in the universe, primarily produced by stellar nucleosynthesis during the advanced stages of stellar evolution. Unlike light elements formed shortly after the Big Bang, xenon is created by neutron capture processes in massive stars and during cataclysmic events.

Xenon is mainly produced by two nucleosynthesis processes: the s process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars and the r process (rapid neutron capture) during supernova explosions and neutron star mergers. These processes create the nine stable isotopes of xenon observed in nature. Stellar winds from AGB stars and supernova ejecta subsequently enrich the interstellar medium with xenon.

In the solar system, xenon exhibits an intriguing anomaly known as the "missing xenon anomaly." Earth's atmosphere is depleted in xenon compared to predictions based on solar and meteoritic abundances. This enigma suggests that xenon may have been trapped in deep terrestrial minerals under high pressure or lost to space during the early stages of Earth's formation. Studying xenon isotopic ratios in meteorites, planetary atmospheres, and noble gases trapped in rocks provides crucial information about the history of the solar system.

The nine stable isotopes of xenon (\(\,^{124}\mathrm{Xe}\) to \(\,^{136}\mathrm{Xe}\)) have distinct abundances reflecting their varied nucleosynthetic origins. \(\,^{129}\mathrm{Xe}\) is particularly interesting because it partially originates from the radioactive decay of extinct \(\,^{129}\mathrm{I}\) (half-life of 15.7 million years), offering valuable temporal constraints on the formation of the solar system. \(\,^{136}\mathrm{Xe}\) can undergo double beta decay, an extremely rare nuclear process studied in fundamental particle physics.

Xenon plays a central role in modern fundamental physics research. Detectors using several tons of ultra-pure liquid xenon, installed in deep underground laboratories, are employed to detect hypothetical dark matter particles (WIMPs) and study neutrino properties. The exceptional purity, high density, and scintillation properties of xenon make it an ideal candidate for these fundamental physics experiments seeking to unravel the mysteries of the invisible universe.

Xenon was discovered in 1898 by British chemists William Ramsay (1852-1916) and Morris Travers (1872-1961) at University College London. This discovery followed those of krypton and neon as part of their systematic research on rare atmospheric gases. Ramsay and Travers isolated xenon by fractional distillation of liquid air, separating components based on their different boiling points. After evaporating krypton, they discovered an even heavier gaseous residue that emitted a bright blue light when electrically excited in a discharge tube.

The name xenon comes from the Greek xenos (ξένος), meaning "stranger" or "unknown," reflecting the discoverers' surprise at this unexpected gas. Ramsay received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 for his discovery of noble gases (helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon). For several decades, xenon was considered completely chemically inert. This certainty was shattered in 1962 when British chemist Neil Bartlett synthesized the first xenon compound, xenon hexafluoroplatinate, revolutionizing our understanding of noble gas reactivity and opening a new chapter in chemistry.

N.B.:

Xenon lamps have revolutionized automotive and cinematographic lighting since the 1990s. Their bright white light, close to the solar spectrum, offers better night visibility and superior color rendering compared to traditional halogen lamps. IMAX cinema projectors use very high-power xenon lamps to project onto giant screens with exceptional brightness. However, the rarity of xenon (only 0.087 parts per million in air) makes it one of the most expensive gases in the world, with prices reaching several thousand euros per kilogram. This rarity is driving the industry to develop alternative technologies such as LEDs while seeking to recycle xenon from used lamps to preserve this precious resource.

Xenon (symbol Xe, atomic number 54) is a noble gas in group 18 of the periodic table, consisting of fifty-four protons, usually seventy-eight neutrons (for the most common isotope), and fifty-four electrons. It has nine natural stable isotopes: \(\,^{124}\mathrm{Xe}\) (0.095%), \(\,^{126}\mathrm{Xe}\) (0.089%), \(\,^{128}\mathrm{Xe}\) (1.910%), \(\,^{129}\mathrm{Xe}\) (26.401%), \(\,^{130}\mathrm{Xe}\) (4.071%), \(\,^{131}\mathrm{Xe}\) (21.232%), \(\,^{132}\mathrm{Xe}\) (26.909%), \(\,^{134}\mathrm{Xe}\) (10.436%), and \(\,^{136}\mathrm{Xe}\) (8.857%).

At room temperature, xenon is a monatomic, colorless, odorless, and generally chemically inert gas. However, unlike lighter noble gases (helium, neon, argon, krypton), xenon can form chemical compounds under certain conditions, particularly with fluorine and oxygen. Xenon is the densest natural noble gas, with an atmospheric concentration of about 0.087 parts per million by volume. Xe gas has a density of about 5.894 g/L at standard temperature and pressure, making it approximately 4.5 times denser than air. The temperature at which liquid and solid states can coexist (melting point): 161.40 K (-111.75 °C). The temperature at which it transitions from liquid to gas (boiling point): 165.051 K (-108.099 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenon-124 — \(\,^{124}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 70 | 123.905893 u | ˜ 0.095% | Stable (theoretically radioactive) | Lightest isotope; theoretical double electron capture with half-life > 10¹⁴ years. |

| Xenon-126 — \(\,^{126}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 72 | 125.904274 u | ˜ 0.089% | Stable | Rare isotope produced by the s process of stellar nucleosynthesis. |

| Xenon-128 — \(\,^{128}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 74 | 127.903531 u | ˜ 1.910% | Stable | Mainly produced by the s process in AGB stars. |

| Xenon-129 — \(\,^{129}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 75 | 128.904779 u | ˜ 26.401% | Stable | Very abundant isotope; partially produced by decay of extinct \(\,^{129}\mathrm{I}\) ; important tracer in geochronology and cosmochemistry. |

| Xenon-130 — \(\,^{130}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 76 | 129.903508 u | ˜ 4.071% | Stable | Used in dark matter and neutrino detectors. |

| Xenon-131 — \(\,^{131}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 77 | 130.905082 u | ˜ 21.232% | Stable | Second most abundant isotope; used in hyperpolarized xenon MRI for lung imaging. |

| Xenon-132 — \(\,^{132}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 78 | 131.904153 u | ˜ 26.909% | Stable | Most abundant isotope; common fission product in nuclear reactors. |

| Xenon-133 — \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 79 | 132.905910 u | Not natural | 5.243 days | Radioactive ß\(^-\) decay to \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Cs}\) ; used in medical lung imaging and to detect clandestine nuclear tests. |

| Xenon-134 — \(\,^{134}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 80 | 133.905394 u | ˜ 10.436% | Stable | Abundant isotope produced by neutron capture s process. |

| Xenon-135 — \(\,^{135}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 81 | 134.907227 u | Not natural | 9.14 hours | Radioactive ß\(^-\) ; important fission product; strong neutron absorber ("neutron poison" in reactors). |

| Xenon-136 — \(\,^{136}\mathrm{Xe}\,\) | 54 | 82 | 135.907219 u | ˜ 8.857% | Stable (theoretically radioactive) | Can undergo double beta decay (measured half-life > 10²¹ years); studied in neutrino physics. |

| Other isotopes — \(\,^{110}\mathrm{Xe}-\,^{123}\mathrm{Xe},\,^{125}\mathrm{Xe},\,^{127}\mathrm{Xe},\,^{137}\mathrm{Xe}-\,^{147}\mathrm{Xe}\) | 54 | 56-69, 71, 73, 83-93 | — | Not natural | milliseconds — several days | Artificially produced radioactive isotopes; used in nuclear research, medicine, and detection of nuclear tests. |

N.B.:

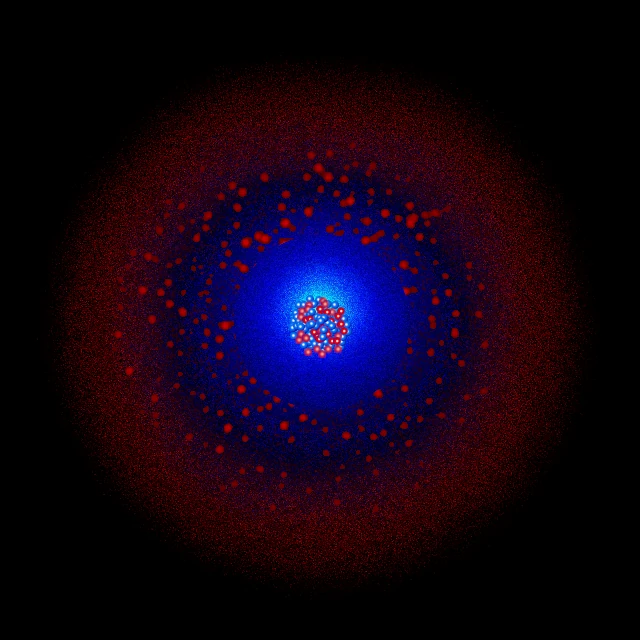

Electron shells: How electrons organize around the nucleus.

Xenon has 54 electrons distributed across five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁶, or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁶. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(8).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶, forming a complete and stable shell.

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰, forming a complete shell.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰, forming a complete shell.

O shell (n=5): contains 8 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶. This outer shell is complete with 8 valence electrons (octet configuration), giving xenon the characteristic stability of noble gases.

Xenon, a member of group 18 (noble gases), has 8 valence electrons (5s² 5p⁶) forming a stable octet electronic configuration. This configuration traditionally explains the chemical inertness of noble gases. However, xenon, being the heaviest natural noble gas, has outer electrons relatively far from the nucleus (large atomic radius) and thus less strongly bound, allowing it to form chemical compounds, unlike lighter noble gases such as helium, neon, and argon. The high polarizability of xenon facilitates interactions with highly electronegative elements like fluorine and oxygen.

Xenon is extremely rare in Earth's atmosphere (0.087 ppm) but has remarkable and diverse applications. Its use in xenon lamps for high-intensity automotive lighting and cinema projectors exploits its ability to produce bright light close to the solar spectrum. In medicine, it serves as a general anesthetic with neuroprotective properties. In space exploration, xenon is the preferred propellant for ion engines in satellites and probes. In fundamental physics, ultra-pure liquid xenon detectors search for dark matter and study neutrinos. Its unique ability to form chemical compounds (fluorides, oxides) has revolutionized noble gas chemistry since 1962.

Xenon has eight valence electrons (5s² 5p⁶) forming a complete outer shell (octet). This stable configuration explains its chemical inertness under normal conditions. For more than sixty years after its discovery, xenon was considered totally inert, incapable of forming chemical bonds. This belief was spectacularly refuted in 1962 when Neil Bartlett synthesized the first xenon compound, xenon hexafluoroplatinate (Xe[PtF₆]), demonstrating that noble gases could react. Unlike lighter noble gases, xenon has relatively accessible valence electrons due to their distance from the nucleus, the shielding effect of many inner electron shells, and its high polarizability.

Xenon primarily forms compounds with fluorine (the most electronegative element) and oxygen. Xenon fluorides include XeF₂ (difluoride), XeF₄ (tetrafluoride), and XeF₆ (hexafluoride), where xenon exhibits oxidation states of +2, +4, and +6, respectively. These compounds are powerful oxidizing and fluorinating agents used in chemical synthesis. Xenon also forms oxides such as XeO₃ (trioxide) and XeO₄ (tetroxide), as well as oxyfluorides (XeOF₂, XeOF₄, XeO₂F₂) and perxenic acid (H₄XeO₆), although these compounds are thermodynamically unstable and potentially explosive. Organometallic compounds of xenon, coordination complexes, and even xenon-nitrogen, xenon-carbon, and xenon-gold bonds have been synthesized under special conditions (low temperatures, inert matrices), constantly expanding the fascinating field of xenon chemistry.

Despite its surprising ability to form compounds, xenon remains chemically inert under normal temperature and pressure conditions, making it valuable for many technological applications that exploit this stability. Its high density (about 5.9 times that of air), low thermal conductivity, and inertness make it an excellent filling gas for high-performance thermal insulation windows and incandescent bulbs. Ionized xenon in an electric field produces intense, bright light with a spectrum close to sunlight, used in high-intensity discharge lamps for automotive lighting (xenon headlights), IMAX cinema projectors, professional photographic flash systems, and architectural projectors.