Bromine was independently discovered by two chemists in 1825-1826. The French chemist Antoine-Jérôme Balard (1802-1876), then only 23 years old and working as an assistant at the Faculty of Sciences in Montpellier, was the first to isolate and formally identify bromine in 1826. Balard was studying the mother liquors from the salt marshes of Montpellier, highly concentrated salt residues after seawater evaporation for salt production.

By treating these mother liquors with chlorine, Balard observed the appearance of a reddish-brown substance, which he managed to isolate by distillation. He quickly recognized it as a new chemical element, distinct from chlorine and iodine. He initially proposed the name muride (from the Latin muria, brine), but the French chemist Louis-Jacques Thénard suggested bromine, from the Greek bromos, meaning stench, in reference to the pungent and suffocating odor characteristic of bromine.

Simultaneously, the German chemist Carl Jacob Löwig (1803-1890), then a student in Heidelberg, had isolated bromine in 1825 from a mineral water source in Bad Kreuznach. However, Löwig delayed publishing his results because he wanted to produce a larger quantity of the element for further study. When he finally presented his work in 1826, Balard had already published his discovery, thus receiving official recognition for the discovery of bromine.

The discovery of bromine completed the then-known halogen family (chlorine, iodine, bromine), reinforcing the understanding of periodic relationships between elements. Bromine immediately distinguished itself by its unique property of being the only non-metal liquid at room temperature, a characteristic it shares only with mercury among all elements.

Bromine (symbol Br, atomic number 35) is a halogen in group 17 of the periodic table. Its atom has 35 protons, usually 44 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{79}\mathrm{Br}\)) and 35 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁵.

At room temperature, elemental bromine is a dense, mobile reddish-brown liquid, formed by diatomic Br₂ molecules. It is the only non-metal liquid under standard conditions, a remarkable property that distinguishes it from all other halogens (fluorine and chlorine are gaseous, iodine is solid, and astatine is extremely rare and radioactive).

Liquid bromine has a high density of 3.12 g/cm³, about three times that of water. It is moderately volatile at room temperature, producing toxic and corrosive reddish-brown vapors that easily spread in the air. These vapors have a characteristic penetrating and irritating odor, recognizable even at very low concentrations.

Bromine melts at -7.2 °C (265.9 K), forming an orange-reddish crystalline solid with an orthorhombic structure. It boils at 58.8 °C (332.0 K), producing dense reddish-brown vapors. This relatively narrow temperature range for the liquid state (about 66 °C) explains why bromine is liquid under normal laboratory conditions but can easily be solidified or vaporized.

Melting point of bromine: 265.9 K (-7.2 °C).

Boiling point of bromine: 332.0 K (58.8 °C).

Critical point of bromine: 588 K (315 °C) at 103 bar.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromine-79 — \(\,^{79}\mathrm{Br}\,\) | 35 | 44 | 78.918337 u | ≈ 50.69 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope of bromine, slightly more abundant in natural bromine. |

| Bromine-81 — \(\,^{81}\mathrm{Br}\,\) | 35 | 46 | 80.916290 u | ≈ 49.31 % | Stable | Second stable isotope, almost as abundant as bromine-79. Used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Bromine-77 — \(\,^{77}\mathrm{Br}\,\) | 35 | 42 | 76.921379 u | Synthetic | ≈ 57.0 hours | Radioactive (electron capture). Positron emitter used in PET imaging for medical research. |

| Bromine-80 — \(\,^{80}\mathrm{Br}\,\) | 35 | 45 | 79.918529 u | Synthetic | ≈ 17.7 minutes | Radioactive (β⁻, 92%; β⁺, 8%). Produced in nuclear reactors, used in research. |

| Bromine-82 — \(\,^{82}\mathrm{Br}\,\) | 35 | 47 | 81.916804 u | Synthetic | ≈ 35.3 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Gamma emitter used as a tracer in hydrology and nuclear medicine. |

| Bromine-83 — \(\,^{83}\mathrm{Br}\,\) | 35 | 48 | 82.915175 u | Synthetic | ≈ 2.40 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Produced by nuclear fission, used in fundamental research. |

N.B.:

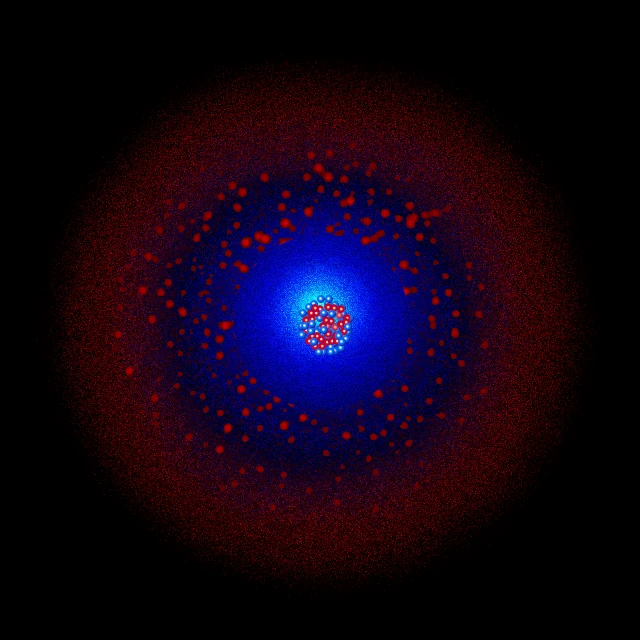

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Bromine has 35 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁵, or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁵. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(7).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. The presence of the complete 3d subshell influences the chemical properties of bromine.

N shell (n=4): contains 7 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁵. These seven electrons are the valence electrons of bromine, with one electron missing to complete the octet.

The 7 electrons in the outer shell (4s² 4p⁵) are the valence electrons of bromine. With one electron missing to reach the stable noble gas configuration of krypton, bromine is extremely reactive and strongly tends to gain an electron to form the bromide ion Br⁻.

The most common oxidation state of bromine is -1, where it gains an electron to form the bromide ion Br⁻ with the configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶, isoelectronic with krypton. Bromides are extremely stable and represent the most common form of bromine in nature, especially in the oceans where bromide is present at a concentration of about 65 mg/L.

Bromine also exhibits positive oxidation states when combined with more electronegative elements, notably oxygen and fluorine. The +1 state appears in hypobromous acid (HBrO) and hypobromites, which are powerful but unstable oxidants. The +3 state exists in bromous acid (HBrO₂) and bromites, which are also unstable.

The +5 oxidation state is found in bromic acid (HBrO₃) and bromates, which are energetic oxidants used in various industrial applications. These compounds are more stable than their lower oxidation state counterparts. The +7 state appears in perbromic acid (HBrO₄) and perbromates, the most powerful oxidants in bromine chemistry, first synthesized in 1968.

Intermediate oxidation states such as +4 in bromine dioxide (BrO₂) are rare and unstable. Elemental bromine (state 0) forms diatomic Br₂ molecules stabilized by a single covalent bond.

The electronegativity of bromine (2.96 on the Pauling scale) is lower than that of chlorine (3.16) but higher than that of iodine (2.66), reflecting its intermediate position in the halogen group. This moderate electronegativity explains why bromine can form both ionic (with metals) and covalent (with non-metals) compounds.

Bromine is a powerful oxidant, although less reactive than chlorine and fluorine. It reacts vigorously with most metals to form metal bromides. With sodium, the reaction is particularly spectacular: 2Na + Br₂ → 2NaBr, producing an intense flame and white smoke of sodium bromide.

Bromine reacts with hydrogen at high temperature or under UV irradiation to form hydrogen bromide (HBr), a strong acid in aqueous solution: H₂ + Br₂ → 2HBr. This reaction is much slower than that of chlorine with hydrogen and usually requires a catalyst or activation energy.

With water, bromine reacts slowly to form a mixture of hydrobromic acid and hypobromous acid: Br₂ + H₂O ⇌ HBr + HBrO. This reaction is reversible and the equilibrium favors the reactants. Bromine water, an aqueous solution saturated with bromine, is yellow-orange and has oxidizing properties.

Bromine reacts with bases to form bromides and hypobromites (in cold) or bromates (in hot): 3Br₂ + 6OH⁻ → 5Br⁻ + BrO₃⁻ + 3H₂O (in hot). This disproportionation reaction is characteristic of halogens in basic media.

Bromine vigorously attacks most organic compounds, particularly unsaturated hydrocarbons (alkenes and alkynes). The addition reaction of bromine to double bonds is instantaneous and causes the characteristic decoloration of the bromine solution, turning reddish-brown to colorless: C₂H₄ + Br₂ → C₂H₄Br₂. This reaction is used as a qualitative test to detect double bonds.

Bromine is also capable of substituting hydrogen atoms in organic compounds, in the presence of light or catalysts. The organobromine compounds thus formed are widely used in organic synthesis as reaction intermediates. Bromine can also form charge-transfer complexes with certain aromatic molecules.

With red phosphorus, bromine reacts violently to form phosphorus tribromide: 2P + 3Br₂ → 2PBr₃. With sulfur, it forms various sulfur bromides such as S₂Br₂. Bromine also oxidizes many transition metals to their higher oxidation states.

Elemental bromine is extremely toxic and corrosive. Bromine vapors severely irritate the eyes, respiratory tract, and mucous membranes, even at very low concentrations. Inhalation of bromine vapors can cause serious lung damage, delayed pulmonary edema, and, in severe cases, death. The occupational exposure limit is 0.1 ppm over 8 hours, reflecting the high toxicity of this compound.

Skin contact with liquid bromine causes painful and slow-healing chemical burns. Bromine rapidly penetrates the skin, causing deep and necrotic lesions. Splashes in the eyes can cause permanent damage, including blindness. The use of appropriate personal protective equipment (resistant gloves, safety goggles, fume hood) is mandatory when handling bromine.

Bromine must be handled in glass or certain resistant plastic containers (PTFE, PVDF), as it attacks most metals and organic materials. Storage requires hermetically sealed amber glass bottles in ventilated and refrigerated areas to minimize evaporation.

Certain organobromine compounds, particularly polybrominated flame retardants (PBDE), raise environmental and health concerns. These persistent substances accumulate in the food chain and can disrupt the endocrine and nervous systems. Several brominated flame retardants have been progressively banned or restricted in many countries.

Methyl bromide, once widely used as an agricultural fumigant, has been identified as an ozone layer depleter and is now strictly controlled by the Montreal Protocol. Its use has been virtually eliminated in developed countries, with only a few critical applications still authorized under exemption.

Bromine is synthesized in stars through several stellar nucleosynthesis processes. The two stable isotopes of bromine (\(\,^{79}\mathrm{Br}\) and \(\,^{81}\mathrm{Br}\)) are mainly produced during the explosive burning of silicon in type II supernovae, as well as by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars.

The cosmic abundance of bromine is extremely low, about 7×10⁻¹⁰ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the rarest elements in the universe. This rarity is explained by several factors: bromine has an odd number of protons (Br, Z = 35), making it less stable than even-numbered elements, and it lies in a region of the nuclear stability curve where nucleosynthesis processes are less efficient.

The isotopic ratio ⁷⁹Br/⁸¹Br in the solar system is about 1.03, reflecting the relative contributions of different nucleosynthesis processes. Analysis of this ratio in primitive meteorites and refractory inclusions provides information on the conditions of the solar system's formation and the contribution of different stellar populations to its chemical composition.

The spectral lines of neutral and ionized bromine are difficult to observe in stellar spectra due to the very low cosmic abundance of this element. However, bromine lines have been detected in a few chemically peculiar stars and in some exotic astrophysical objects. These observations help understand the chemical enrichment of stars and the chemical evolution of galaxies.

N.B.:

Bromine is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.0003% by mass (3 ppm), making it a relatively rare element. It generally does not form its own ores but is mainly extracted from seawater and natural brines where it is present as the bromide ion (Br⁻).

The ocean is the main source of bromine, with an average concentration of 65 mg/L (about 65 ppm), representing more than 100 billion tons of bromine dissolved in the world's oceans. Marine bromine mainly comes from the weathering of continental rocks and submarine volcanic activity. Terrestrial sources include brine from salt deposits, salt lakes, and certain thermal springs.

Global bromine production is about 550,000 tons per year, mainly extracted in the United States (Arkansas, Michigan), China, Israel (Dead Sea), and Jordan. Extraction is done by chemical oxidation of the bromide ion to elemental bromine, usually using chlorine as an oxidant: 2Br⁻ + Cl₂ → Br₂ + 2Cl⁻. Bromine is then purified by distillation.

The world's major producers closely control the bromine market due to its strategic nature for several industries. The United States and Israel have historically dominated this market, although China has become a major producer in recent decades. The price of bromine fluctuates according to industrial demand, particularly in the flame retardant and oil drilling fluid sectors.

The use of bromine is evolving in response to environmental and health concerns. Many brominated flame retardants are being gradually replaced by less problematic alternatives. However, new applications are emerging, particularly in energy storage (zinc-bromine batteries) and fine chemistry, maintaining stable demand for this element.