Cerium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Cerium is a significant product of both nucleosynthesis processes, explaining its relatively high abundance among rare earth elements.

The cosmic abundance of cerium is about 1.2×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it the most abundant rare earth element in the universe. This high abundance is due to cerium's favorable position on the nuclear stability curve, particularly the isotope Ce-140, which has a magic number of neutrons (82), giving it exceptional stability.

Spectral lines of neutral cerium (Ce I) and ionized cerium (Ce II) are observable in stellar spectra, although less prominent than those of lighter elements. Cerium is used as a tracer of stellar and galactic chemical enrichment. The cerium/iron ratio in metal-poor stars helps constrain the relative contributions of the s and r processes in the history of galactic nucleosynthesis.

Some chemically peculiar stars, particularly Ap stars and highly magnetic white dwarfs, show cerium abundance anomalies. These variations are attributed to atomic diffusion processes in stellar atmospheres under the influence of intense magnetic fields and radiative pressures. Studying these anomalies provides insights into physical processes in extreme stellar atmospheres.

Cerium is named after the asteroid Ceres, discovered in 1801 by Giuseppe Piazzi. The near-simultaneous discovery of the asteroid and the element led to this naming. Cerium was the first rare earth element identified and isolated, paving the way for the subsequent discovery of all lanthanides.

In 1803, Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779-1848) and Wilhelm Hisinger (1766-1852) in Sweden, and independently Martin Heinrich Klaproth (1743-1817) in Germany, discovered a new earthy oxide in cerite mineral from Bastnäs, Sweden. They demonstrated it was an unknown element, which they named cerium. The parallel and independent discovery in two locations reflects the intense scientific activity of the period.

Isolating metallic cerium proved difficult due to its reactivity and tendency to form alloys. In 1825, Carl Gustav Mosander (1797-1858), a student of Berzelius, obtained impure cerium metal by reducing cerium chloride with potassium. It was not until the early 20th century that electrolytic and metallothermic reduction methods allowed the production of pure cerium metal in industrial quantities.

Cerium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 66 ppm, making it the 25th most abundant element on Earth, more abundant than copper or lead. It is by far the most abundant rare earth, accounting for about 50% of the total mass of rare earths in the Earth's crust. The main cerium minerals are bastnasite ((Ce,La)CO₃F), containing 40-75% rare earth oxides, and monazite ((Ce,La,Th)PO₄), containing 50-70% rare earth oxides.

Global production of cerium oxides is about 80,000 to 100,000 tons per year. China dominates production with about 85-90% of the global total, followed by the United States, Australia, Myanmar, and India. This extreme geographical concentration makes cerium a strategically critical element despite its geological abundance.

Cerium metal is mainly produced by reducing cerium oxide (CeO₂) with calcium metal at high temperatures (calciothermic reduction), or by electrolysis of molten cerium chloride. Global annual production of cerium metal is about 20,000 tons. Cerium recycling remains limited, accounting for less than 1% of supply, although efforts are intensifying to recover cerium from used automotive catalysts and fluorescent lamps.

Cerium (symbol Ce, atomic number 58) is the first element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the f-block rare earths of the periodic table. Its atom has 58 protons, usually 82 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{140}\mathrm{Ce}\)) and 58 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹ 5d¹ 6s² or [Xe] 4f² 6s², depending on the state.

Cerium is a ductile, bright silver-gray metal that oxidizes rapidly in air, forming an oxide layer that does not effectively protect the underlying metal. Cerium uniquely exhibits complex polymorphism with four allotropic forms. The α-cerium to γ-cerium transition under pressure involves a spectacular volume contraction of 14-17%, an exceptional phenomenon among elements.

Cerium melts at 798 °C (1071 K) and boils at 3443 °C (3716 K). Its density varies with the allotropic form: γ-cerium (stable at room temperature) has a density of 6.77 g/cm³, while α-cerium has a density of 8.16 g/cm³. Cerium is a good conductor of electricity and heat, with electrical conductivity about 7 times lower than that of copper.

Cerium is a highly reactive metal, especially at high temperatures. It spontaneously ignites in humid air at room temperature and burns vigorously when heated, producing a bright white flame. Cerium reacts vigorously with water, producing cerium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Fine cerium powder or shavings are pyrophoric and spontaneously ignite in air.

Melting point of cerium: 1071 K (798 °C).

Boiling point of cerium: 3716 K (3443 °C).

Cerium exhibits an allotropic transition under pressure with an exceptional volume contraction of 14-17%.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerium-136 — \(\,^{136}\mathrm{Ce}\,\) | 58 | 78 | 135.907172 u | ≈ 0.185 % | Stable | Rare stable isotope of cerium, representing about 0.2% of the natural total. |

| Cerium-138 — \(\,^{138}\mathrm{Ce}\,\) | 58 | 80 | 137.905991 u | ≈ 0.251 % | Stable | Rare stable isotope, slightly more abundant than Ce-136. |

| Cerium-140 — \(\,^{140}\mathrm{Ce}\,\) | 58 | 82 | 139.905439 u | ≈ 88.450 % | Stable | Ultra-dominant isotope of cerium, representing nearly 88.5% of the total. Magic number of neutrons (82). |

| Cerium-142 — \(\,^{142}\mathrm{Ce}\,\) | 58 | 84 | 141.909244 u | ≈ 11.114 % | ≈ 5×10¹⁶ years | Radioactive (double β⁻), extremely long half-life, practically stable on a human timescale. |

| Cerium-141 — \(\,^{141}\mathrm{Ce}\,\) | 58 | 83 | 140.908276 u | Synthetic | ≈ 32.5 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Important fission product, used as a tracer in nuclear medicine and research. |

| Cerium-144 — \(\,^{144}\mathrm{Ce}\,\) | 58 | 86 | 143.913647 u | Synthetic | ≈ 284.9 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Significant fission product, used as a heat source in radioisotope thermoelectric generators. |

N.B.:

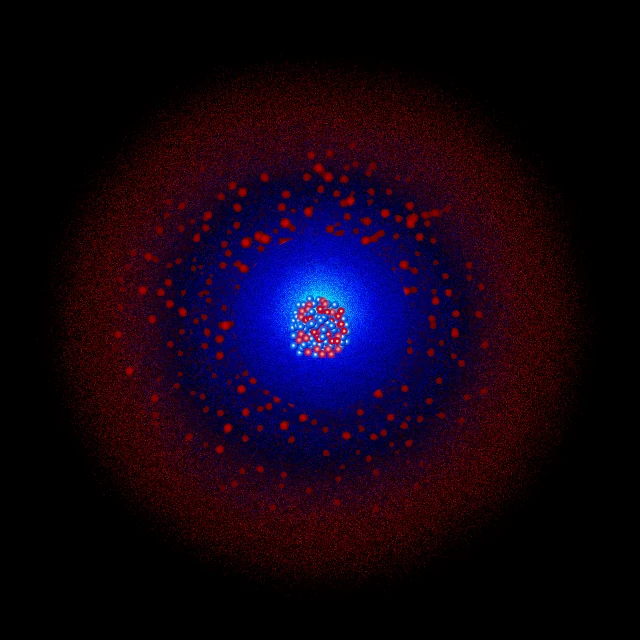

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Cerium has 58 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration is unusual and can be written as either [Xe] 4f¹ 5d¹ 6s² or [Xe] 4f² 6s², depending on the energy state. This ambiguity results from the exceptional energetic proximity of the 4f and 5d orbitals in cerium, leading to variable electronic configurations depending on the chemical environment. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(19-20) P(2-3).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable and complete structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 19 or 20 electrons depending on the configuration: 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹ 5d¹⁰ or 5s² 5p⁶ 4f² 5d⁹. The 4f subshell begins to fill.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 or 3 electrons in the 6s² or 6s² 6p¹ subshells. These electrons are the valence electrons of cerium.

Cerium typically has 4 valence electrons, although this number can vary. The main oxidation states are +3 and +4. The +3 state is characteristic of all lanthanides, where cerium loses three electrons to form the Ce³⁺ ion with the configuration [Xe] 4f¹. The +4 state is unique among light lanthanides and particularly stable for cerium, forming the Ce⁴⁺ ion with the configuration [Xe], isoelectronic with xenon.

The +4 state appears in many important cerium compounds, notably cerium dioxide (CeO₂ or ceria), which is the most industrially significant cerium compound. This ability to easily exist in two oxidation states makes cerium an excellent oxidizing agent and an exceptional redox catalyst. The easy interconversion between Ce³⁺ and Ce⁴⁺ underlies many catalytic applications of cerium.

Cerium compounds with oxidation state +2 have been synthesized under extreme conditions, but these compounds are extremely unstable and rapidly oxidize. The chemistry of cerium is therefore essentially dominated by the +3 and +4 states, with a preference for the +4 state under oxidizing conditions.

Cerium is highly reactive with oxygen and oxidizes rapidly in air, forming a cerium oxide layer that does not effectively protect the metal. At high temperatures, cerium spontaneously ignites in air and burns with an intense bright white flame, producing cerium dioxide (CeO₂): Ce + O₂ → CeO₂. Fine cerium powder is pyrophoric and spontaneously ignites at room temperature, requiring handling in an inert atmosphere.

Cerium reacts slowly with cold water but vigorously with hot water or steam, producing cerium(III) hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas: 2Ce + 6H₂O → 2Ce(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. This reaction accelerates significantly at high temperatures. Cerium(III) hydroxide is a moderately strong base that readily precipitates from aqueous solutions.

Cerium reacts vigorously with halogens to form trihalides or tetrahalides: 2Ce + 3Cl₂ → 2CeCl₃ or Ce + 2F₂ → CeF₄. Cerium easily dissolves in acids, even diluted ones, with hydrogen release: 2Ce + 6HCl → 2CeCl₃ + 3H₂↑. It also reacts with sulfur to form cerium sulfide (Ce₂S₃), with nitrogen at high temperatures to form cerium nitride (CeN), and with carbon to form cerium carbide (CeC₂).

The most remarkable chemical property of cerium is its ability to easily oscillate between the +3 and +4 oxidation states. Cerium(IV) is a powerful oxidant in acidic solutions, capable of oxidizing many organic and inorganic compounds. This redox property is exploited in numerous catalytic applications, particularly in automotive catalytic converters where cerium facilitates the oxidation of pollutants and the reduction of nitrogen oxides.

The dominant application of cerium, accounting for about 40-50% of global consumption, is its use in automotive catalytic converters in the form of cerium oxide (CeO₂ or ceria). Cerium plays a crucial role in reducing vehicle pollutant emissions, significantly contributing to improved urban air quality since the 1980s.

The main function of cerium in three-way catalysts (TWC) is oxygen storage and release. Cerium oscillates between Ce³⁺ (oxide CeO₁.₅) and Ce⁴⁺ (oxide CeO₂) states, capturing excess oxygen under fuel-rich conditions and releasing it under lean conditions, thus maintaining an optimal air-fuel ratio for the simultaneous conversion of carbon monoxide, unburned hydrocarbons, and nitrogen oxides.

Modern catalytic converters typically contain 10-30% cerium oxide by mass, often combined with zirconia (CeO₂-ZrO₂) to improve thermal stability and oxygen storage capacity. A typical automobile contains 30-100 grams of cerium in its catalyst. Current research aims to increase catalytic efficiency while reducing the content of precious metals (platinum, palladium, rhodium) through optimized cerium formulations.

Ultrafine cerium dioxide (CeO₂) is the standard polishing material for high-precision optical glasses for over a century. Its unique combination of moderate hardness, active surface chemistry, and controlled particle size allows for optical surfaces of exceptional flatness and finish, unmatched by other abrasives.

Cerium polishing is essential for manufacturing high-end photographic lenses, astronomical optics, telescope mirrors, laser components, deep UV lithography lenses in semiconductor manufacturing, and high-resolution flat panel display glasses. The polishing mechanism combines mechanical action (gentle abrasion) and chemical action (surface hydrolysis of glass), producing surfaces with roughness below 0.5 nanometers.

The global optics industry consumes about 10,000 to 15,000 tons of cerium oxide annually for polishing, representing about 10-15% of total cerium demand. An 8-meter diameter telescope mirror requires several hundred kilograms of cerium oxide to achieve the required optical finish. Despite research on alternatives, no material has yet matched cerium's performance for extreme precision optical polishing.

Mischmetal is an alloy of light rare earths typically containing 45-50% cerium, 25% lanthanum, 15-18% neodymium, 5% praseodymium, and traces of other lanthanides. This alloy has remarkable pyrophoric properties: it produces intense sparks when rubbed against a rough surface, due to the ignition of microscopic shavings torn off by friction.

The major historical application of mischmetal was lighter flints, invented in the 1900s. Modern lighters still use this principle, with mischmetal producing the sparks needed to ignite gas. This consumer application represented significant cerium demand for decades. Mischmetal is also used as a metallurgical additive to desulfurize steels and improve their mechanical properties, as well as a nucleation agent in light aluminum and magnesium alloys.

Cerium and its compounds have low to moderate toxicity. Soluble cerium compounds can cause skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation. Chronic exposure to cerium dust can cause occupational pneumoconiosis (ceriosis) in exposed workers in polishing and metallurgical industries, although this condition is rare and generally benign.

Ingestion of soluble cerium compounds can cause gastrointestinal disorders, nausea, and vomiting. Cerium mainly accumulates in the liver and bone skeleton in cases of chronic exposure. Toxicological studies on animals suggest hepatic toxicity and calcium metabolism disruption at high doses. However, significant human exposure to cerium remains relatively rare outside specialized occupational environments.

Cerium oxide nanoparticles, increasingly used in diesel fuels, catalysts, and coatings, raise emerging environmental and health concerns. Their small size allows them to penetrate deeply into the lungs and potentially cross biological barriers. In vitro studies show pro-oxidant effects and cellular damage at certain concentrations, although cerium nanoparticles also exhibit paradoxical antioxidant properties under other conditions.

Environmental exposure to cerium mainly comes from rare earth mining, metallurgical refining, and emission of cerium nanoparticles from diesel additives and catalytic converter wear. Cerium concentrations in soils near rare earth mines can be significantly elevated, reaching several hundred ppm. Occupational exposure standards typically set the limit at 3-5 mg/m³ for respirable dust. No specific standards yet exist for cerium nanoparticles in the environment, reflecting the early state of knowledge about their ecotoxicological impacts.