Dysprosium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in low- to medium-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch), with a significant contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae. Current nucleosynthesis models estimate that about 60-70% of solar dysprosium comes from the s-process, and 30-40% from the r-process. This mixed origin makes it an interesting tracer of both nucleosynthesis processes.

The cosmic abundance of dysprosium is about 1.9×10⁻¹² times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it slightly more abundant than terbium. Due to its even atomic number (Z=66), it is more abundant than its odd neighbors (Tb-65 and Ho-67), in accordance with the Oddo-Harkins rule. In the lanthanide series, dysprosium is part of the "heavy rare earths" whose abundances gradually decrease with increasing atomic number, except for the gadolinium anomaly (Z=64), which exhibits particular stability.

The dysprosium/europium (Dy/Eu) ratio in stars is used as an indicator of the balance between s- and r-processes in the history of the Galaxy. Since europium is almost exclusively produced by the r-process, a high Dy/Eu ratio in a star indicates a significant contribution from the s-process. Young, metal-rich stars generally have higher Dy/Eu ratios than old, metal-poor stars, reflecting the progressive accumulation of s-process products during galactic evolution.

Dysprosium has been detected in the spectra of many stars, including metal-poor stars in the galactic halo. Its spectral lines (mainly Dy II) are relatively accessible in astronomical spectroscopy. In chondritic meteorites, dysprosium shows an abundance similar to that of the sun, confirming its stellar origin. Isotopic studies of dysprosium in refractory inclusions of primitive meteorites have provided crucial information on the conditions of the solar system's formation and the possible presence of anomalous stellar material (isotopic anomalies).

Dysprosium takes its name from the ancient Greek δυσπρόσιτος (dysprositos), meaning "difficult to reach" or "difficult to access". This name was chosen by its discoverer to reflect the difficulties he encountered in isolating this element from other rare earths. Unlike other lanthanides named after places or people, the name of dysprosium directly describes the complexity of its chemical separation.

Dysprosium was discovered in 1886 by the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1838-1912), famous for also discovering gallium (1875) and samarium (1879). Lecoq de Boisbaudran was working on holmia samples (holmium oxide) and, after more than 30 fractional crystallization attempts, succeeded in separating a new oxide which he identified as belonging to an unknown element. He observed distinct spectral lines and named the new element "dysprosium" due to the extreme difficulties in its purification.

The isolation of dysprosium in pure form was a major technical challenge for decades after its discovery. It was not until the early 20th century, with the development of ion exchange and solvent extraction techniques, that dysprosium was obtained with sufficient purity for complete characterization. The metal itself was first produced in 1906 by reducing dysprosium fluoride with metallic calcium, but it was not until the 1950s that reliable industrial processes were developed.

Dysprosium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 5.2 ppm (parts per million), making it more abundant than terbium but less than gadolinium. Among the heavy rare earths, it is relatively more abundant.

The main ores containing dysprosium are bastnasite ((Ce,La,Nd,Dy)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Dy,Th)PO₄), where it typically represents 0.5 to 1% of the total rare earth content, and xenotime (YPO₄) where it can be more concentrated.

Global production of dysprosium oxide (Dy₂O₃) is about 100 to 200 tons per year, which is significant but remains low compared to light rare earths such as cerium or neodymium. Due to its strategic importance for permanent magnets, dysprosium is one of the most expensive rare earths, with typical prices of 300 to 600 dollars per kilogram of oxide (with peaks above 2000 $/kg during supply tensions). China dominates production with about 85-90% of the world total.

Dysprosium metal is mainly produced by metallothermic reduction of dysprosium fluoride (DyF₃) with metallic calcium in an inert argon atmosphere. Global annual production of dysprosium metal is about 50 to 100 tons. Recycling dysprosium from used permanent magnets has become a strategic priority and is the subject of intensive development, with the first industrial processes now operational.

Dysprosium (symbol Dy, atomic number 66) is the tenth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the f-block rare earths of the periodic table. Its atom has 66 protons, 98 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{164}\mathrm{Dy}\)) and 66 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁰ 6s². This configuration gives dysprosium exceptional magnetic properties.

Dysprosium is a silvery, shiny, and relatively stable metal in air. It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature. Dysprosium has exceptional magnetic properties: it is strongly paramagnetic and exhibits several magnetic transitions. It becomes antiferromagnetic below 178 K (-95 °C), then ferromagnetic below 85 K (-188 °C). Although these temperatures are very low, dysprosium is crucial in alloys such as Terfenol-D (with terbium and iron) which exhibit giant magnetostrictive properties at room temperature.

Dysprosium melts at 1412 °C (1685 K) and boils at 2567 °C (2840 K). Like most lanthanides, it has high melting and boiling points. Dysprosium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 1381 °C where its crystal structure changes from hexagonal close-packed (HCP) to body-centered cubic (BCC). Its electrical conductivity is poor, about 25 times lower than that of copper. Dysprosium also exhibits electrical resistivity that varies strongly with the magnetic field (magnetoresistance).

Dysprosium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, but oxidizes slowly to form Dy₂O₃. It oxidizes more rapidly when heated and burns to form the oxide: 4Dy + 3O₂ → 2Dy₂O₃. Dysprosium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form dysprosium(III) hydroxide Dy(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids. The metal must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere.

Melting point of dysprosium: 1685 K (1412 °C).

Boiling point of dysprosium: 2840 K (2567 °C).

Néel temperature (antiferromagnetic transition): 178 K (-95 °C).

Curie temperature (ferromagnetic transition): 85 K (-188 °C).

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysprosium-156 — \(\,^{156}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 90 | 155.924283 u | ≈ 0.06 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope, very rare in nature. |

| Dysprosium-158 — \(\,^{158}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 92 | 157.924409 u | ≈ 0.10 % | Stable | Very low abundance stable isotope. |

| Dysprosium-160 — \(\,^{160}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 94 | 159.925197 u | ≈ 2.34 % | Stable | Significant stable isotope among natural isotopes. |

| Dysprosium-161 — \(\,^{161}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 95 | 160.926933 u | ≈ 18.91 % | Stable | Important stable isotope, one of the most abundant. |

| Dysprosium-162 — \(\,^{162}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 96 | 161.926798 u | ≈ 25.51 % | Stable | Stable isotope, among the most abundant in the natural mixture. |

| Dysprosium-163 — \(\,^{163}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 97 | 162.928731 u | ≈ 24.90 % | Stable | Major stable isotope, with abundance similar to 162Dy. |

| Dysprosium-164 — \(\,^{164}\mathrm{Dy}\,\) | 66 | 98 | 163.929175 u | ≈ 28.18 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope in nature (~28%). |

N.B. :

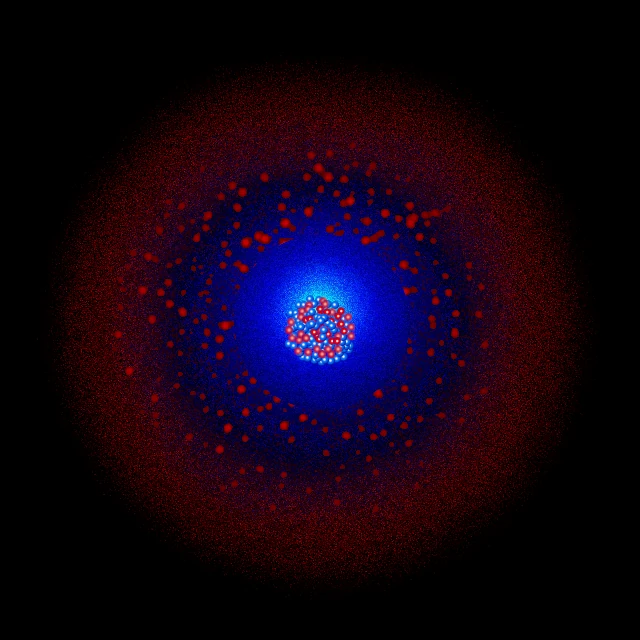

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Dysprosium has 66 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁰ 6s² has ten electrons in the 4f subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(28) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 28 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁰ 5d⁰. The ten 4f electrons give dysprosium its exceptional magnetic properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of dysprosium.

Dysprosium effectively has 12 valence electrons: ten 4f¹⁰ electrons and two 6s² electrons. Dysprosium exclusively exhibits the +3 oxidation state in its stable compounds. In this state, dysprosium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Dy³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁹. This ion has nine electrons in the 4f subshell and exhibits a strong magnetic moment (10.6 μB) due to its unpaired electrons.

Unlike some lanthanides such as europium or ytterbium, dysprosium does not form stable +2 or +4 oxidation states under normal conditions. A few dysprosium(II) and (IV) compounds have been synthesized under extreme conditions but are very unstable and of laboratory curiosity. The +3 state is therefore the only chemically and technologically significant one.

The chemistry of dysprosium is dominated by the +3 state. The Dy³⁺ ion has an ionic radius of 105.2 pm (for coordination number 8) and forms generally pale yellow complexes in aqueous solution. Its magnetic properties are exploited in magnetocaloric materials and magnetic memory glasses. Dysprosium salts are paramagnetic and exhibit weak luminescence compared to other lanthanides such as europium or terbium.

Dysprosium metal is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin protective layer of Dy₂O₃. At high temperature (above 200 °C), it oxidizes rapidly and burns to form the oxide: 4Dy + 3O₂ → 2Dy₂O₃. Dysprosium(III) oxide is a white to pale yellow solid with a cubic C-type rare earth structure. In fine powder form, dysprosium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Dysprosium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form dysprosium(III) hydroxide Dy(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Dy + 6H₂O → 2Dy(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous white solid with low solubility. As with other lanthanides, the reaction is not violent but is observable over time.

Dysprosium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides: 2Dy + 3F₂ → 2DyF₃ (white fluoride); 2Dy + 3Cl₂ → 2DyCl₃ (pale yellow chloride). Dysprosium dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) with the release of hydrogen and the formation of the corresponding Dy³⁺ salts: 2Dy + 6HCl → 2DyCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Dysprosium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperature (300-400 °C) to form DyH₂ hydride, then DyH₃ at higher temperature. With sulfur, it forms Dy₂S₃ sulfide. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperature (>1000 °C) to form DyN nitride, and with carbon to form DyC₂ carbide. Dysprosium also forms many coordination complexes with organic ligands, although this chemistry is less developed than for some other lanthanides.

The most remarkable property of dysprosium is its strong magnetic moment. The Dy³⁺ ion has the highest theoretical magnetic moment of all rare earth ions (10.6 μB, Bohr magnetons) due to its nine unpaired electrons in the 4f subshell. Although dysprosium metal is only ferromagnetic at very low temperatures, this powerful magnetic ion is crucial when incorporated into materials such as Nd-Fe-B magnets or Terfenol-D alloys. Dysprosium significantly improves the coercivity (resistance to demagnetization) and thermal stability of these materials.

The most important and strategic application of dysprosium is its use as an additive in neodymium-iron-boron (Nd-Fe-B) based permanent magnets. These magnets, the most powerful commercially available, lose their magnetic properties (especially their coercivity) at high temperatures (above 100-150 °C). The addition of a few percent of dysprosium (typically 2-10% by weight, partially replacing neodymium) significantly increases the maximum operating temperature, allowing their use in critical applications such as electric vehicle motors and wind turbine generators.

Dysprosium acts by substituting for neodymium in the tetragonal Nd₂Fe₁₄B crystal structure. The Dy³⁺ ion has a higher magnetic anisotropy than the Nd³⁺ ion, which increases the energy required to reverse the magnetization of the material (coercivity). This improvement is particularly important at high temperatures, where thermal agitation tends to misalign the magnetic moments. Dysprosium preferentially concentrates at grain boundaries, where it inhibits the propagation of magnetic domain walls, thus strengthening resistance to demagnetization.

Dysprosium-doped Nd-Fe-B magnets are essential for:

The growing demand for dysprosium, coupled with its limited and geographically concentrated production (China), makes it a critical raw material. Intensive research aims to reduce the dysprosium content of magnets (e.g., through microstructural optimization, such as fine-grained magnets), develop efficient recycling processes, and find partial substitutes (such as terbium, also rare and expensive) or technological alternatives (rare-earth-free magnets such as ferrites, or new electric motor concepts). However, in the short and medium term, dysprosium remains irreplaceable for high-temperature applications.

Terfenol-D is an alloy based on terbium, dysprosium, and iron with an approximate composition of Tb0.3Dy0.7Fe₂. Dysprosium, in combination with terbium, allows the adjustment of magnetic properties to achieve giant magnetostriction (change in dimension under magnetic field) at room temperature while minimizing magnetic anisotropy. Dysprosium also helps reduce the cost of the material compared to a purely terbium-based alloy.

Applications include precision actuators (positioning systems, injectors), sensors (force sensors, hydrophones), ultrasonic transducers (medical imaging, industrial cleaning), and vibration control systems. Although the Terfenol-D market is smaller than that of Nd-Fe-B magnets, it represents a very high value-added application where the unique properties of the alloy justify its high cost.

Dysprosium has a relatively high thermal neutron absorption cross-section (about 940 barns for the natural isotopic mixture). Some of its isotopes, particularly dysprosium-164 (2700 barns) and dysprosium-161 (600 barns), have even higher cross-sections. This property allows dysprosium (in the form of Dy₂O₃ oxide or metal) to be used in nuclear reactor control rods and neutron shielding.

Like gadolinium, dysprosium can be used as a "burnable poison" in nuclear fuel to compensate for excess reactivity at the beginning of the cycle. By absorbing neutrons, it controls the chain reaction and is gradually transmuted into other elements. However, its use is less common than that of gadolinium due to its higher cost.

Dysprosium and its compounds have low to moderate chemical toxicity, comparable to other lanthanides. Soluble salts can cause irritation. No severe acute toxicity or carcinogenic effects have been demonstrated. The LD50 (median lethal dose) of dysprosium chloride in rats is about 300-500 mg/kg intravenously. Like other lanthanides, dysprosium has no known biological role.

In case of exposure, dysprosium mainly accumulates in the liver and bones, with very slow elimination (biological half-life of several years for the bone fraction). General population exposure is extremely low, limited to workers in the relevant industries.

The major environmental impacts are related to rare earth mining in general: waste production, acid waters, radioactive residues (thorium, uranium in monazite). The extraction of one kilogram of dysprosium requires the processing of several tons of ore.

Recycling dysprosium from used permanent magnets is a strategic priority for several reasons:

Recycling techniques include hydrometallurgy (acid dissolution followed by solvent extraction) and pyrometallurgy (vacuum melting). The major challenge is the collection and sorting of end-of-life products containing magnets. Pilot projects and the first industrial-scale recycling plants have been set up, particularly in Japan and Europe. The current recycling rate is still low (less than 1%) but is expected to increase rapidly with regulations and economic incentives.

Occupational exposure occurs in mines, separation plants, magnet manufacturers, and recycling sites. Dust from dysprosium compounds must be controlled by ventilation and protective equipment. No specific occupational disease is associated with dysprosium, but general precautions for metal dusts apply.