Polonium is a heavy element produced exclusively by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae or neutron star mergers. Due to its radioactive isotopes and relatively short half-lives (the longest, \(^{209}\mathrm{Po}\), has a half-life of only 125.2 years), there is virtually no primordial polonium in the universe. Any polonium present at the formation of the solar system has long since decayed. The polonium found on Earth today is either artificial or results from the decay of uranium and thorium in natural radioactive chains.

Several isotopes of polonium appear as intermediate products in the four primordial radioactive decay chains:

These very short-lived isotopes are constantly produced and disappear in uranium- and thorium-containing minerals, contributing to natural radioactivity. \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) (Radium F), with a half-life of 138.376 days, is the longest-lived member of the uranium-238 chain and can accumulate in measurable quantities.

\(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) is used as a natural tracer in Earth sciences. Produced by the decay of radon-222 (gas) in the atmosphere, it deposits on terrestrial and oceanic surfaces. Its ratio with its longer-lived "parent," \(^{210}\mathrm{Pb}\) (half-life 22.3 years), allows dating of recent marine sediments (over a few hundred years), studying ocean mixing processes, bioproductivity, and particle transport in the atmosphere.

Polonium was named by its discoverers, Marie and Pierre Curie, in 1898, in homage to Marie's native Poland (then partitioned between the Russian Empire, Austria-Hungary, and Prussia). It was a patriotic and political act, intended to draw attention to the cause of Polish independence, as the country no longer existed on maps. It was the first element named after a country.

While studying the radioactivity of pitchblende (a uranium ore), Marie Curie noticed that it was higher than could be explained by the uranium content alone. She and her husband Pierre undertook the titanic task of chemical purification of tons of ore. In July 1898, they announced the discovery of a new element, which they named polonium. They characterized it by its intense radioactivity and chemical similarity to bismuth. A few months later, they would discover radium, which was even more radioactive. These discoveries earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903 (shared with Henri Becquerel).

Isolating polonium in weighable quantities was extremely difficult due to its low abundance and high radioactivity. It was only after many years of processing ores that microscopic amounts of pure polonium salts were obtained. The first observation of the polonium spectrum was made in 1910. Gram-scale production only became possible with the development of nuclear reactors.

Today, polonium-210 is produced artificially in two main ways:

Global production is very low, on the order of a few hundred grams per year, mainly in Russia. Its cost is extremely high (hundreds of thousands of dollars per gram for high-purity \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\)), due to the complexity of its production and separation, and the associated risks.

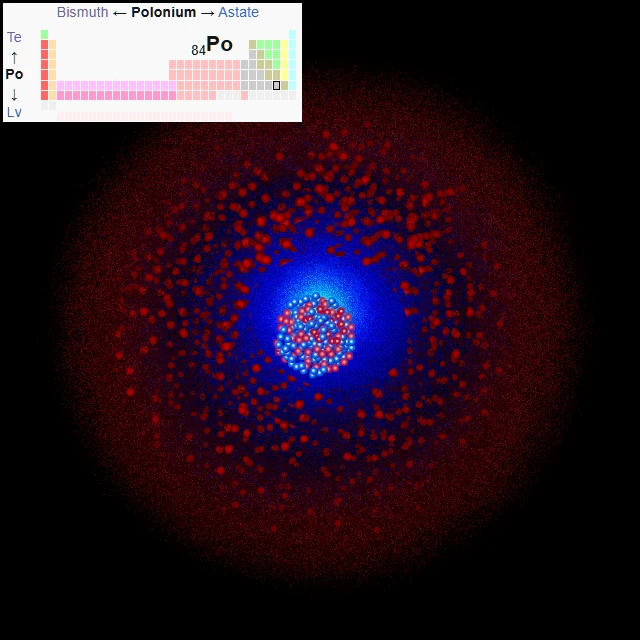

Polonium (symbol Po, atomic number 84) is a post-transition metal, located in group 16 (oxygen group or chalcogens) of the periodic table, along with oxygen, sulfur, selenium, tellurium, and livermorium. It is the only element in this group that is a metal (at room temperature). Its atom has 84 protons and, depending on the isotope, 122 to 136 neutrons. The isotope \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) has 126 neutrons. Its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁴, with six valence electrons (6s² 6p⁴).

Polonium is a silvery-gray, soft metal, chemically similar to its cousins tellurium and bismuth.

Its intense radioactivity quickly damages its crystalline structure and causes self-irradiation.

Polonium melts at 254 °C (527 K) and boils at 962 °C (1235 K). Its decay heat can distort these measurements for macroscopic samples.

Chemically, polonium is a fairly reactive metal, similar to tellurium. It dissolves in acids to form Po(IV) solutions (pink) and oxidizes easily in air. It forms compounds in oxidation states -2, +2, +4, and +6, with +4 being the most stable. Its compounds are often colored (e.g., PoCl₄ is yellow, PoBr₄ is red). However, studying its chemistry is extremely difficult and dangerous due to its intense radioactivity.

Density (α-Po): 9.32 g/cm³.

Melting point: 527 K (254 °C).

Boiling point: 1235 K (962 °C).

Crystal structure (α): Simple cubic (unique among elements).

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁴.

Main oxidation state: +4.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Decay mode | Remarks / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polonium-208 — \(^{208}\mathrm{Po}\) | 84 | 124 | 207.981246 u | Trace (radiogenic) | 2.898 years (α) | Medium-lived isotope, present in the thorium chain. Can be produced artificially. |

| Polonium-209 — \(^{209}\mathrm{Po}\) | 84 | 125 | 208.982430 u | Trace (radiogenic) | 125.2 years (α, 99.99%; CE, 0.001%) | Isotope with the longest natural half-life. Mainly produced by α decay of \(^{213}\mathrm{Bi}\). |

| Polonium-210 — \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) | 84 | 126 | 209.982874 u | Trace (radiogenic) | 138.376 days (α) | The most important and well-known isotope. Intense alpha radioactivity (5.3 MeV). Used in antistatic sources, thermoelectric generators, and infamously as a poison. Produced from \(^{209}\mathrm{Bi}\) by neutron irradiation. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Polonium has 84 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁴ has six valence electrons in the 6th shell (s² p⁴). This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(6), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s² 6p⁴.

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 6 electrons (6s² 6p⁴).

Polonium has 6 valence electrons (6s² 6p⁴). Its chemistry resembles that of tellurium, but with a greater tendency toward lower oxidation states due to the onset of the inert pair effect. The main oxidation states are:

The chemistry of polonium is poorly explored due to the extreme dangers associated with its handling.

Polonium metal oxidizes rapidly in air to form polonium dioxide (PoO₂), a yellow solid. When heated in air, it can form mixed oxides.

Very few polonium compounds have been prepared and studied in detail, always in minute quantities and with extreme precautions.

When a high-energy alpha particle (such as that from \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\)) strikes a beryllium-9 nucleus, a nuclear reaction occurs: \(^9\mathrm{Be} + \alpha \rightarrow \,^{12}\mathrm{C} + n\). This reaction produces a neutron. Polonium-beryllium (Po-Be) sources were therefore portable neutron sources, used:

However, the short half-life of \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) (138 days) made these sources impractical, requiring frequent replacement. They have been largely replaced by sources using americium-241 or californium-252.

The intense decay of \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) releases a large amount of heat (140 W/g). This heat can be converted into electricity using thermocouples (Seebeck effect). Polonium-210 was used in some of the first RTGs developed by the Soviets to power equipment in remote locations (beacons, weather stations). However, its short half-life resulted in a rapid decrease in power. For long-duration space missions, it was abandoned in favor of plutonium-238 (half-life 87.7 years).

Polonium-210 is one of the most toxic substances known. Its danger stems from several factors:

The median lethal dose (LD50) for humans by ingestion is estimated at only 1 microgram (1 µg) of \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\), or an activity of about 11 GBq.

Symptoms of acute poisoning (as in the Litvinenko case) appear after a few days and include:

Difficult detection: Polonium-210 does not emit significant gamma radiation (only a weak gamma at 803 keV in 0.001% of decays). Direct detection requires a special alpha counter or measurement of radioactivity in excreta (urine, feces). Diagnosis is often delayed.

Limited treatment: There is no specific antidote. Treatment is symptomatic (transfusions, growth factors, antibiotics) and aims to eliminate polonium:

Polonium-210 is naturally present in trace amounts everywhere (soil, water, air) due to decay chains. Higher concentrations are found in uranium ores, phosphate fertilizers (containing uranium), and… tobacco smoke. Tobacco plants absorb polonium present in soils and fertilizers, and it concentrates in the leaves. Smoking is thus a significant source of internal exposure to \(^{210}\mathrm{Po}\) for smokers.

Due to its extreme toxicity and potential for malicious use, polonium-210 is subject to very strict international controls. It is classified as a Category 1 radioactive material (the most dangerous) by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Its trade, transport, and use are closely monitored. Facilities authorized to handle it must comply with exceptionally high nuclear safety and security standards.

Waste containing polonium must be packaged to ensure long-term containment, given its 138-day half-life. After a few years of storage in suitable containers, the activity has decreased significantly. The waste is then managed like other short-lived medium-activity radioactive waste.

Civilian applications of polonium are today very limited and declining, replaced by other safer or more practical radioisotopes (Am-241, Pu-238, Cf-252). Its main interest remains:

Polonium will forever be associated with the genius and courage of Marie Curie, as well as the sinister shadow of its deadly toxicity.