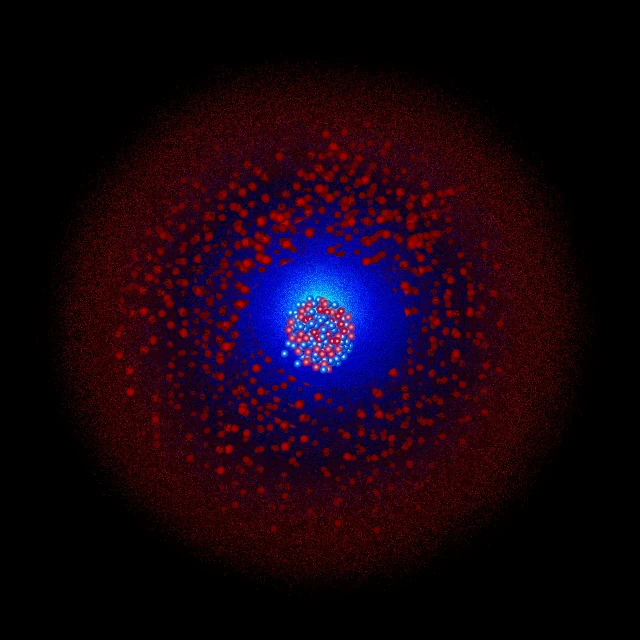

Lutetium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch) of low to medium mass. As the last stable lanthanide and the heaviest element in the series, it represents the endpoint of rare earth production via neutron capture. Lutetium shows a very low contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture), estimated at less than 5-10% of its solar abundance, making it, along with ytterbium, one of the purest tracers of the s-process.

The cosmic abundance of lutetium is about 3.5×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the least abundant rare earths, comparable to thulium and about 2.3 times less abundant than ytterbium. Its extreme rarity is explained by several factors: its odd atomic number (Lu, Z = 71) according to the Oddo-Harkins rule, its position at the end of the neutron capture chain where capture cross-sections become weaker, and the fact that it is the heaviest stable lanthanide (the next, promethium, is radioactive).

Lutetium is an important tracer of the s-process, particularly for studying the final stages of neutron capture nucleosynthesis. The lutetium/europium (Lu/Eu) ratio in stars is extremely sensitive to the s-process contribution, as europium is dominated by the r-process. A high Lu/Eu ratio is a characteristic signature of stars enriched in s-process elements. Additionally, certain spectral lines of lutetium are temperature-sensitive, allowing this element to be used as a "thermometer" to determine the temperatures of stellar atmospheres in certain particular stars.

The detection of lutetium in stellar atmospheres is difficult due to its rarity, but it has been achieved in several stars using modern high-resolution spectrographs. The lines of the Lu II ion are the most used. In geochemistry, lutetium, with its radioactive isotope Lu-176 (half-life of 37.8 billion years), is used for rock dating (Lu-Hf system). This dating system is particularly useful for studying the early formation of the Earth's crust and the evolution of the mantle, as lutetium and hafnium have distinct geochemical behaviors during magmatic processes.

Lutetium takes its name from Lutetia, the Latin name for the city of Paris. This name was chosen by the French chemist Georges Urbain, who discovered the element, to honor his hometown. It is one of the few elements named after Paris, along with francium (also discovered in Paris). The use of the Latin name Lutetia recalls the historical origins of the city, founded by the Parisii, a Gallic people.

Lutetium was discovered almost simultaneously and independently by three researchers in 1907. The French chemist Georges Urbain (1872-1938) succeeded in separating Marignac's ytterbia into two oxides: neo-ytterbium (which ultimately retained the name ytterbium) and lutetium. Almost at the same time, the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach (1858-1929), inventor of the incandescent mantle, separated the same oxides and named them aldebaranium and cassiopeium. Meanwhile, the American chemist Charles James (1880-1928), working at the University of New Hampshire, also achieved the separation. After a controversy, the name "lutetium" proposed by Urbain was finally adopted internationally, although the spelling "lutetium" is used in some English-speaking countries.

The separation of lutetium from ytterbium was one of the most difficult analytical challenges in rare earth chemistry, due to the great similarity of their chemical properties. The three discoverers used extremely laborious fractional crystallization methods, requiring thousands of repetitions. Urbain mainly used fractional crystallization of nitrates, while von Welsbach used that of bromates. It was only with the development of ion exchange techniques in the 1950s that high-purity lutetium became relatively accessible.

Lutetium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.5 ppm (parts per million), making it one of the rarest rare earths, comparable to thulium and promethium (but the latter is practically absent as it is radioactive). It is about 6 times less abundant than ytterbium. The main minerals containing lutetium are monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Lu,Th)PO₄) and bastnasite ((Ce,La,Nd,Lu)CO₃F), where it typically represents 0.003 to 0.01% of the total rare earth content, and xenotime (YPO₄) where it can be slightly more concentrated. It is also found in euxenite and gadolinite.

The world production of lutetium oxide (Lu₂O₃) is about 10 to 20 tons per year, making it one of the least produced rare earths. Due to its extreme rarity and highly specialized, high value-added applications, lutetium is one of the most expensive rare earths, with typical prices of $5,000 to $15,000 per kilogram of oxide (or more for high purity grades). China dominates production, but even there, lutetium is produced in minuscule quantities.

Lutetium metal is mainly produced by metallothermic reduction of lutetium fluoride (LuF₃) with metallic calcium in an inert argon atmosphere. The annual world production of lutetium metal is only a few hundred kilograms. The recycling of lutetium is virtually non-existent due to the infinitesimal quantities used and the extreme difficulty of recovering it from complex finished products.

Lutetium (symbol Lu, atomic number 71) is the fifteenth and last element in the lanthanide series, closing the rare earths of the f-block of the periodic table. Its atom has 71 protons, usually 104 neutrons (for the most abundant stable isotope \(\,^{175}\mathrm{Lu}\)), and 71 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹ 6s². This configuration has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and one electron in the 5d subshell, which distinguishes lutetium from other lanthanides and brings it chemically closer to group 3 elements (scandium, yttrium).

Lutetium is a silvery, shiny, relatively hard and dense metal. Among the lanthanides, it is one of the hardest and densest (9.84 g/cm³). It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature, unlike ytterbium which has a face-centered cubic structure. Lutetium is paramagnetic at room temperature due to the unpaired electron in the 5d subshell. It has the highest melting and boiling points of all the lanthanides.

Lutetium melts at 1663 °C (1936 K) and boils at 3402 °C (3675 K). These exceptionally high melting and boiling points make it the most refractory lanthanide. Lutetium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 1675 °C where its crystal structure changes from hexagonal close-packed (HCP) to body-centered cubic (BCC). Its electrical conductivity is poor, about 20 times lower than that of copper. Lutetium is a good heat conductor for a lanthanide.

Lutetium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, but slowly oxidizes to form Lu₂O₃. It oxidizes more rapidly when heated and burns to form the oxide: 4Lu + 3O₂ → 2Lu₂O₃. Lutetium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form lutetium(III) hydroxide Lu(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids. The metal must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere.

Melting point of lutetium: 1936 K (1663 °C) - the highest of the lanthanides.

Boiling point of lutetium: 3675 K (3402 °C) - the highest of the lanthanides.

Density: 9.84 g/cm³ - one of the densest lanthanides.

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

Hardness: Relatively hard among lanthanides.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lutetium-175 — \(\,^{175}\mathrm{Lu}\,\) | 71 | 104 | 174.940771 u | ≈ 97.41 % | Stable | Major stable isotope of natural lutetium. |

| Lutetium-176 — \(\,^{176}\mathrm{Lu}\,\) | 71 | 105 | 175.942686 u | ≈ 2.59 % | 3.78×10¹⁰ years | Beta-minus radioactive with extremely long half-life. Used in geochronology (Lu-Hf system). |

| Lutetium-177 — \(\,^{177}\mathrm{Lu}\,\) | 71 | 106 | 176.943758 u | Synthetic | ≈ 6.65 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Major medical isotope used in targeted radiotherapy (theranostics). |

| Lutetium-177m — \(\,^{177m}\mathrm{Lu}\,\) | 71 | 106 | 176.943758 u | Synthetic | ≈ 160.4 days | Metastable nuclear isomer of Lu-177. Gamma emitter used in research and calibration. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Lutetium has 71 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹ 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and one electron in the 5d subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(32) P(3), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screening.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 32 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴ 5d¹. The completely filled 4f subshell and the presence of a 5d electron characterize the chemistry of lutetium.

P shell (n=6): contains 3 electrons in the 6s² and 5d¹ subshells (although 5d belongs to the n=5 shell, it is energetically close to 6s).

Lutetium effectively has 17 valence electrons: fourteen 4f¹⁴ electrons, two 6s² electrons, and one 5d¹ electron. However, lutetium almost exclusively exhibits the +3 oxidation state in its stable compounds. In this state, lutetium loses its two 6s electrons and its 5d electron to form the Lu³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴. This ion has a completely filled 4f subshell and is diamagnetic, which is unique among trivalent lanthanide ions (all others are paramagnetic).

Unlike some lanthanides such as europium or ytterbium, lutetium does not form a stable +2 oxidation state under normal conditions. A few lutetium(II) compounds have been synthesized under extreme conditions but are very unstable. The +3 state is therefore the only chemically significant one. This exclusive stability of the +3 state, combined with the small ionic radius of Lu³⁺ (100.1 pm for coordination number 8, the smallest of all lanthanides), gives lutetium a distinct chemistry that brings it closer to yttrium and scandium than to other lanthanides.

The chemistry of lutetium is therefore dominated by the +3 state. The Lu³⁺ ion forms generally colorless complexes in aqueous solution (the 4f → 4f transition is forbidden and very weak). Its salts are diamagnetic. The small ionic radius of Lu³⁺ gives it a high charge density, which results in coordination chemistry with a preference for oxygen-donor ligands and a tendency to form complexes with higher coordination numbers.

Lutetium metal is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin protective layer of Lu₂O₃. At high temperature (above 200 °C), it oxidizes rapidly and burns to form the oxide: 4Lu + 3O₂ → 2Lu₂O₃. Lutetium(III) oxide is a white solid with a cubic C-type rare earth structure. In fine powder form, lutetium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Lutetium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form lutetium(III) hydroxide Lu(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Lu + 6H₂O → 2Lu(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous white solid with low solubility. As with other lanthanides, the reaction is not violent but is observable over the long term.

Lutetium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides: 2Lu + 3F₂ → 2LuF₃ (white fluoride); 2Lu + 3Cl₂ → 2LuCl₃ (white chloride). Lutetium dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) with the release of hydrogen and the formation of the corresponding Lu³⁺ salts: 2Lu + 6HCl → 2LuCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Lutetium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperature (300-400 °C) to form LuH₂, then LuH₃ at higher temperature. With sulfur, it forms the sulfide Lu₂S₃. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperature (>1000 °C) to form the nitride LuN, and with carbon to form the carbide LuC₂. Lutetium also forms many coordination complexes with organic ligands, although this chemistry is less developed than for some other lanthanides due to its high cost.

The most remarkable property of lutetium is the small size and high stability of its Lu³⁺ ion. With an ionic radius of only 100.1 pm (for coordination number 8), Lu³⁺ is the smallest trivalent ion of all the rare earths. This small size, combined with its high charge, gives Lu³⁺ an exceptionally high charge density. This results in strong ligand polarization, a high affinity for hard ligands (oxygen-donor atoms), and a tendency to form complexes with higher coordination numbers. These properties are exploited in catalysis and advanced materials.

Theranostics is a medical approach that combines therapy and diagnosis using the same or similar agents. Lutetium-177 (¹⁷⁷Lu) is an ideal radioactive isotope for this approach. It emits medium-energy beta particles (β⁻) (max 497 keV, average 133 keV) that are therapeutic, and low-energy gamma rays (113 keV and 208 keV) that allow imaging (scintigraphy). Thus, the same Lu-177-labeled molecule can both treat the tumor (therapy) and visualize its location (diagnosis).

The most established application of Lu-177 is the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), particularly gastroenteropancreatic tumors. The treatment usually uses a somatostatin analog (such as DOTATATE or DOTATOC) conjugated to a chelate (DOTA) that firmly binds Lu-177. This molecule targets somatostatin receptors that are overexpressed on the surface of neuroendocrine tumor cells. Once injected, the compound binds to tumor cells, delivering a high dose of radiation locally while sparing healthy tissues.

Lu-177 is also used to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). In this case, it is coupled with PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen), a protein overexpressed on the surface of prostate cancer cells. ¹⁷⁷Lu-PSMA-617 has shown promising results in the treatment of patients with therapeutic failure, improving survival and quality of life.

Lu-177 is being studied for the treatment of other cancers, including small cell lung cancer, glioblastoma, ovarian cancer, and lymphoma. New molecular targets and vectors are under development to broaden the indications.

Lu-177 is produced mainly by neutron irradiation of ytterbium-176 (¹⁷⁶Yb(n,γ)¹⁷⁷Yb → ¹⁷⁷Lu) in nuclear reactors, or by separation from irradiated ytterbium-176 target. An alternative method uses direct irradiation of lutetium-176 (¹⁷⁶Lu(n,γ)¹⁷⁷Lu), but it produces Lu-177 with radioactive impurities. The growing demand for Lu-177 has created supply tensions and stimulated the development of new production capacities.

Lutetium is used as a promoter in fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalysts, which convert heavy petroleum fractions into lighter, more valuable products (gasoline, diesel, petrochemicals). Y-type zeolites, the main component of FCC catalysts, are often modified with rare earths to improve their thermal and hydrothermal stability, and their catalytic activity. Lutetium, due to its small ionic radius and high charge, is particularly effective in stabilizing the zeolite structure and modulating its acidity.

Lu³⁺ ions replace sodium ions in the exchangeable sites of the zeolite. Their small size and high charge create strong electrostatic fields that polarize hydrocarbon molecules, favoring cracking reactions. In addition, lutetium increases the resistance of the zeolite to deactivation by water vapor at high temperature, which is crucial under the severe conditions of FCC units. Even at very low concentrations (typically less than 0.1% by weight in the catalyst), lutetium can significantly improve performance.

The improvement in activity and selectivity of the FCC catalyst by lutetium increases the yield of gasoline, reduces the production of undesirable by-products, and extends the life of the catalyst. This results in substantial economic gains for refineries. Although lutetium is very expensive, the required quantities are so small that its use can be economically justified in large refineries.

Scintillators are materials that emit light when struck by ionizing radiation. Lutetium is a component of several high-performance scintillators:

LuAG (lutetium aluminum garnet) crystals doped with active ions such as cerium (Ce³⁺) or praseodymium (Pr³⁺) are used as gain media for high-performance lasers. These lasers are studied for applications in precision machining, medicine, and research.

Lutetium oxide (Lu₂O₃) is incorporated into certain special optical glasses to increase their refractive index and dispersion. These glasses are used in high-end camera lenses, microscopes, and other precision optical instruments where the reduction of chromatic aberrations is critical.

The lutetium-176/hafnium-176 isotopic system (¹⁷⁶Lu → ¹⁷⁶Hf, half-life 37.8 billion years) is used to date ancient geological events, particularly the early differentiation of the Earth's crust and mantle. Since lutetium and hafnium have different geochemical behaviors (lutetium is more compatible than hafnium in mantle minerals), their ratio evolves differently in the crust and mantle, allowing the history of continental crust formation to be traced.

Lutetium and its compounds have low chemical toxicity, comparable to other lanthanides. No severe acute toxicity or carcinogenic effects have been demonstrated. As with other rare earths, the main toxicity would be related to interference with calcium metabolism in case of exposure to high doses. Lutetium has no known biological role.

In case of exposure, lutetium behaves like other lanthanides: it accumulates mainly in the liver and bones, with very slow elimination. Exposure of the general population is extremely low, practically nil, due to the extreme rarity of the element and its highly specialized applications.

For the Lu-177 isotope used in nuclear medicine, strict radiation protection precautions are necessary during production, preparation of radiopharmaceuticals, administration to patients, and waste management. Medical personnel must follow radiation protection protocols for beta/gamma emitters. Patients treated with Lu-177 emit radiation and sometimes require special precautions (limitation of contact with relatives, management of excretions) for a few days after injection.

The environmental impacts specifically related to lutetium are negligible due to the minute quantities produced. Lutetium recycling is practically non-existent. Medical waste containing Lu-177 is treated as radioactive waste and stored until complete decay (the half-life of 6.65 days means that after about 10 half-lives, or 67 days, the activity is reduced to less than 0.1% of the initial activity). The development of lutetium recycling methods from medical or industrial waste is unlikely due to prohibitive costs.

Occupational exposure is limited to the very few workers involved in the production of lutetium compounds, the manufacture of Lu-177 radiopharmaceuticals, and the medical use of these products. Standard precautions for metal dusts (for stable lutetium) and radiation protection (for Lu-177) apply. The number of exposed persons is extremely low.