Krypton was discovered on May 30, 1898 by British chemists William Ramsay (1852-1916) and Morris Travers (1872-1961) at University College London. This discovery was part of a remarkable series of noble gas identifications by Ramsay, who had already discovered argon in 1894 with Lord Rayleigh, and terrestrial helium in 1895.

Ramsay and Travers systematically searched for new elements in atmospheric air using the fractional distillation of liquid air. After isolating argon, they suspected the existence of other inert gases in the atmosphere. By slowly evaporating liquid air and analyzing the different fractions by spectroscopy, they discovered neon and krypton in May 1898, followed by xenon a few weeks later.

Krypton was identified by its characteristic emission spectrum, showing particularly intense bright green and yellow-orange lines. Ramsay and Travers chose the name krypton from the Greek kryptos, meaning hidden, in reference to the difficulty of detecting it in the Earth's atmosphere, where it represents only one part per million by volume.

The discovery of krypton, along with neon and xenon, completed the group of noble gases in Mendeleev's periodic table and confirmed the periodicity of chemical properties. William Ramsay received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 for his work on noble gases, including the discovery of argon, helium, neon, krypton, and xenon.

In 1960, krypton acquired fundamental metrological importance when the wavelength of the orange line of krypton-86 was chosen as the new definition of the meter, replacing the platinum-iridium bar of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures. This definition remained in force until 1983, when the meter was redefined based on the speed of light.

Krypton (symbol Kr, atomic number 36) is a noble gas in group 18 of the periodic table. Its atom has 36 protons, usually 48 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{84}\mathrm{Kr}\)) and 36 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶.

Krypton is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless monatomic gas under normal conditions. It is about three times denser than air, with a density of 3.749 g/L at 0 °C and 1 atmosphere. This high density makes it heavier than most common atmospheric gases.

Like all noble gases, krypton has a completely filled outer electron shell (stable octet configuration), giving it exceptional chemical stability and almost no reactivity under normal conditions. This saturated electronic structure explains why krypton naturally exists as isolated atoms rather than molecules.

Krypton liquefies at -153.4 °C (119.8 K) under normal atmospheric pressure and solidifies at -157.4 °C (115.8 K). Liquid krypton is colorless and transparent, while solid krypton forms crystals with a face-centered cubic structure, characteristic of solidified noble gases.

Liquefaction point of krypton: 119.8 K (-153.4 °C).

Solidification point of krypton: 115.8 K (-157.4 °C).

Critical point of krypton: 209.4 K (-63.8 °C) at 55.0 bar.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krypton-78 — \(\,^{78}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 42 | 77.920365 u | ≈ 0.355 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope of natural krypton, the rarest of the stable isotopes. |

| Krypton-80 — \(\,^{80}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 44 | 79.916378 u | ≈ 2.286 % | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope of natural krypton. |

| Krypton-82 — \(\,^{82}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 46 | 81.913484 u | ≈ 11.593 % | Stable | Third most abundant stable isotope of natural krypton. |

| Krypton-83 — \(\,^{83}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 47 | 82.914136 u | ≈ 11.500 % | Stable | Has a nuclear spin used in NMR spectroscopy and medical imaging. |

| Krypton-84 — \(\,^{84}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 48 | 83.911507 u | ≈ 56.987 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of krypton, representing more than half of natural krypton. |

| Krypton-86 — \(\,^{86}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 50 | 85.910610 u | ≈ 17.279 % | Stable | Historically used (1960-1983) to define the meter via its orange emission line. |

| Krypton-81 — \(\,^{81}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 45 | 80.916592 u | Traces | ≈ 229,000 years | Radioactive (electron capture). Produced by cosmic rays, used to date ancient groundwater. |

| Krypton-85 — \(\,^{85}\mathrm{Kr}\,\) | 36 | 49 | 84.912527 u | Synthetic | ≈ 10.76 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Nuclear fission product, used as a tracer and in leak detectors. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Krypton has 36 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶, or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(8).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This shell is completely filled, including the complete d subshell.

N shell (n=4): contains 8 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶. This complete outer shell gives krypton its exceptional stability.

The electronic configuration of krypton, with its completely saturated valence shell (full octet), explains its remarkable chemical inertia. For a long time, noble gases were considered totally inert and incapable of forming chemical compounds.

However, in 1962, British chemist Neil Bartlett revolutionized this concept by synthesizing the first xenon compound. This discovery paved the way for the chemistry of heavy noble gases. Although krypton is less reactive than xenon due to its higher ionization energy, a few krypton compounds have been synthesized under extreme conditions.

Krypton difluoride (KrF₂) was the first stable krypton compound synthesized, in 1963. This white solid forms by irradiating a mixture of krypton and fluorine at low temperature. KrF₂ is an extremely powerful oxidant but remains unstable at room temperature, slowly decomposing into krypton and fluorine.

Other compounds such as KrF⁺ and Kr₂F₃⁺ ions have been characterized, as well as clathrates where krypton molecules are physically trapped in water molecule cages (krypton hydrates) or other host structures. These clathrates are not true chemical compounds but inclusion complexes held together by Van der Waals forces.

Krypton can also form metastable compounds with hydrogen and nitrogen under electrical discharge or irradiation, but these species are extremely unstable and only exist at very low temperatures or for very short durations.

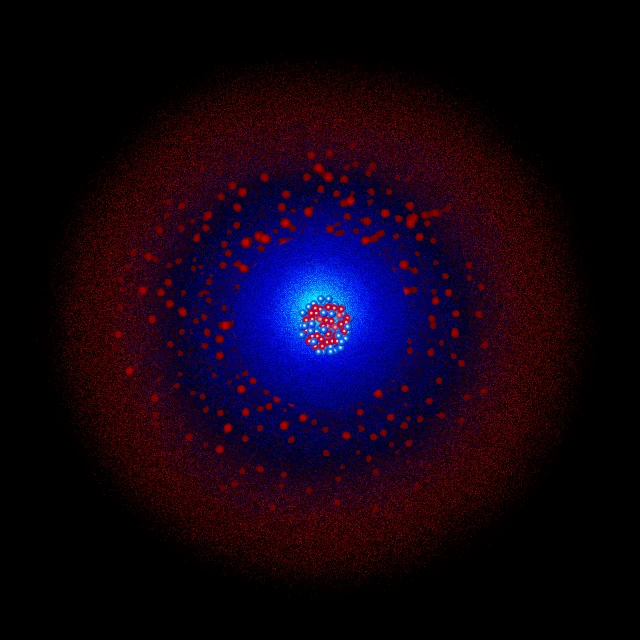

Krypton exhibits a particularly rich and complex emission spectrum when excited by an electrical discharge. Its characteristic spectrum includes many lines in the visible range, notably intense green lines (557.0 nm), yellow-green lines (587.1 nm), and orange lines (605.6 nm and 645.6 nm).

The orange line of krypton-86 at 605.78 nm (transition between levels 2p10 and 5d5) has an exceptionally narrow spectral width, making it the ideal choice for defining the meter from 1960 to 1983. One meter was defined as 1,650,763.73 wavelengths of this radiation in a vacuum, a definition of unprecedented precision at the time.

When excited, krypton emits a bright white light with a strong green component, producing high-quality lighting with excellent color rendering. This property is exploited in krypton discharge lamps used for professional lighting, photography, and projectors.

Krypton also participates in fluorescence and phosphorescence phenomena in certain doped materials. Krypton excimer compounds (excited dimers Kr₂*) emit in the ultraviolet and are used in certain excimer lasers for lithography and ocular surgery.

Krypton is synthesized in stars by several stellar nucleosynthesis processes. Krypton isotopes are mainly produced during silicon burning in type II supernovae, as well as by the s-process (slow neutron capture) and r-process (rapid neutron capture). The six stable isotopes of krypton reflect the contributions of these different nucleosynthesis processes.

The cosmic abundance of krypton is about 5×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the rarest noble gases after xenon. This relative rarity is explained by the difficulties in synthesizing nuclei in this atomic mass region (A ≈ 78-86) and by krypton's position beyond the iron peak in the nuclear stability curve.

Krypton plays an important role in the study of nucleosynthesis and the chemical evolution of the universe. The isotopic ratios of krypton in primitive meteorites, presolar grains, and noble gases trapped in minerals provide valuable information about the conditions in the early solar system and the different stellar populations that contributed to its formation.

Isotopic anomalies in krypton have been discovered in certain refractory inclusions of meteorites, suggesting the presence of components formed in distinct stellar environments before the collapse of the solar nebula. The isotope krypton-81, produced by cosmic rays, is used to date the cosmic exposure events of meteorites and to trace their history in interplanetary space.

The spectral lines of ionized krypton (Kr II, Kr III, Kr IV) have been observed in the spectra of certain hot B and A type stars, as well as in planetary nebulae and supernova remnants. The analysis of these lines allows the study of the physical conditions (temperature, density, ionization) of these astrophysical objects.

N.B.:

Krypton is present in the Earth's atmosphere at a concentration of about 1.14 parts per million by volume (1.14 ppm or 0.000114%), making it one of the rare atmospheric gases. This apparently low concentration nevertheless represents about 15 billion tons of krypton in the entire Earth's atmosphere.

Krypton is industrially extracted by fractional distillation of liquid air, a process developed in the early 20th century. Air is first liquefied by compression and cooling, then the different components are separated according to their boiling points. Krypton, with its boiling point between oxygen and xenon, is isolated in an enriched fraction and then further purified.

Global krypton production is relatively modest, about 8 to 10 tons per year, mainly in Ukraine, Poland, the United States, Iceland, and China. Krypton is one of the most expensive industrial gases due to its atmospheric rarity and the complex process required for its extraction and purification. The price of high-purity krypton can reach several thousand euros per kilogram.

Krypton-85, a radioactive isotope produced by nuclear fission in reactors, has been gradually accumulating in the Earth's atmosphere since the beginning of the nuclear era. Its atmospheric concentration has increased more than 100-fold since 1950, although it remains extremely low (about 1.5 Bq/m³). Krypton-85 is mainly released during the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel and is a useful tracer for studying global atmospheric circulation.

Due to its total chemical inertness, krypton poses no toxicological risk. However, like all inert gases, it can cause asphyxiation by displacing oxygen in confined spaces. Liquid krypton, at -153 °C, presents the usual cryogenic risks (cold burns, material embrittlement).

Hyperpolarized krypton-83 represents a recent innovation in medical imaging, allowing detailed visualization of the lungs by MRI. This technique offers a promising alternative to X-ray imaging for diagnosing lung diseases, with the advantage of avoiding exposure to ionizing radiation.