Germanium holds a special place in the history of chemistry as another brilliant confirmation of Dmitri Mendeleev's (1834-1907) periodic table. In 1871, Mendeleev predicted the existence of an element he called eka-silicon, positioned below silicon in his periodic classification. He described its expected properties with remarkable precision: an atomic mass around 72, a density near 5.5 g/cm³, a high melting point, and the formation of an oxide with the formula EsO₂.

In 1886, the German chemist Clemens Alexander Winkler (1838-1904) discovered germanium while analyzing a silver ore called argyrodite from the Himmelsfürst mine in Saxony. After eliminating all known elements, he identified a new substance whose properties matched Mendeleev's predictions almost perfectly. The measured atomic mass was 72.6 (very close to the predicted 72), and the density was 5.47 g/cm³ (versus 5.5 predicted).

Winkler named the element germanium in honor of his homeland, Germany (Germania in Latin). This discovery, coming 15 years after Mendeleev's prediction, provided powerful validation of the periodic law and demonstrated the predictive power of the periodic table. Mendeleev himself expressed satisfaction with this confirmation, though he initially questioned some of Winkler's measurements before accepting the accuracy of the discovery.

Germanium (symbol Ge, atomic number 32) is a metalloid in group 14 of the periodic table. Its atom has 32 protons, typically 42 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{74}\mathrm{Ge}\)) and 32 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p².

Germanium is a grayish-white, lustrous, hard, and brittle metalloid at room temperature. Its density is 5.323 g/cm³, and it has a relatively high melting point: 938.3 °C (1,211.4 K). The boiling point reaches 2,833 °C (3,106 K), giving germanium a substantial liquid range of nearly 1,900 °C.

Germanium has a diamond-type cubic crystal structure, similar to silicon and carbon (diamond). Each germanium atom is covalently bonded to four neighboring atoms in a tetrahedral arrangement. This crystalline structure explains many of its physical and electronic properties, particularly its semiconductor behavior.

One of germanium's most remarkable properties is its semiconductor characteristics. At room temperature, pure germanium has a small band gap of about 0.67 eV, making it an intrinsic semiconductor. Unlike metals, its electrical conductivity increases with temperature, a defining characteristic of semiconductors.

Germanium exhibits an unusual property for most materials: like water and silicon, it expands upon solidification. The solid phase is less dense than the liquid phase, which has important implications for its crystal growth and processing.

Pure germanium has a characteristic metallic luster and is relatively hard (Mohs hardness of about 6). It is brittle and fractures rather than deforms under stress. Germanium is transparent to infrared radiation, making it valuable for infrared optics and windows in thermal imaging systems.

The melting point (liquid state) of germanium: 1,211.4 K (938.3 °C).

The boiling point (gaseous state) of germanium : 3,106 K (≈ 2,833 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germanium-70 — \(\,^{70}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 38 | 69.924247 u | ≈ 20.38 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope of germanium. Used in nuclear physics research. |

| Germanium-72 — \(\,^{72}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 40 | 71.922076 u | ≈ 27.31 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope. Important in semiconductor applications. |

| Germanium-73 — \(\,^{73}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 41 | 72.923459 u | ≈ 7.76 % | Stable | Only stable germanium isotope with odd neutron number. Has nuclear spin useful for NMR. |

| Germanium-74 — \(\,^{74}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 42 | 73.921178 u | ≈ 36.72 % | Stable | Most abundant natural isotope. Widely used in semiconductor technology. |

| Germanium-76 — \(\,^{76}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 44 | 75.921403 u | ≈ 7.83 % | Stable* | Theoretically unstable (double beta decay), but half-life exceeds 10²¹ years. Used in dark matter detection experiments. |

| Germanium-68 — \(\,^{68}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 36 | 67.928094 u | Synthetic | ≈ 270.8 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Used in PET calibration sources through its decay to ⁶⁸Ga. |

| Germanium-71 — \(\,^{71}\mathrm{Ge}\,\) | 32 | 39 | 70.924951 u | Synthetic | ≈ 11.43 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Product of neutrino detection reactions with ⁷¹Ga. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

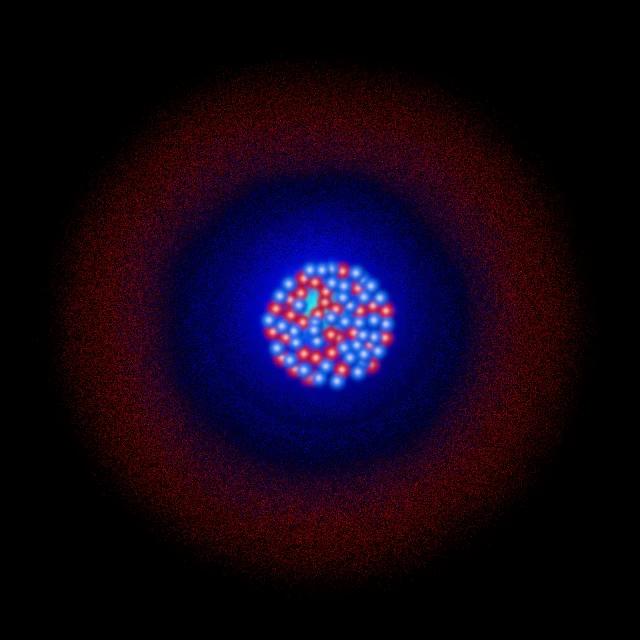

Germanium has 32 electrons distributed across four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is : 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p², or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p². This configuration can also be written : K(2) L(8) M(18) N(4).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This innermost shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. The filled 3d subshell is characteristic of post-transition elements and significantly influences germanium's chemical behavior.

N Shell (n=4): contains 4 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p². These four electrons are the valence electrons of germanium.

The 4 electrons in the outer shell (4s² 4p²) are the valence electrons of germanium. This configuration explains its chemical and semiconductor properties:

The primary oxidation state of germanium is +4, where it shares or loses all four valence electrons to form compounds like GeO₂, GeCl₄, and organogermanium compounds. In this state, germanium achieves a stable noble gas-like configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰, analogous to silicon in its +4 state.

An oxidation state of +2 also exists, particularly in germanium(II) halides such as GeCl₂ or GeO. The +2 state involves the 4p² electrons while retaining the 4s² pair, demonstrating the inert pair effect characteristic of heavier group 14 elements. However, Ge(II) compounds are less stable than Ge(IV) compounds and tend to disproportionate or oxidize easily.

Negative oxidation states (-4) can occur in certain germanides (compounds with electropositive metals like Mg₂Ge), where germanium accepts electrons to complete its valence shell. Metallic germanium exists in the 0 oxidation state in its elemental form.

The presence of the filled 3d¹⁰ subshell immediately before the valence electrons creates an important shielding effect but also contributes to the d-block contraction. This results in a smaller atomic radius than might be expected, making germanium's properties intermediate between those of a metal and a non-metal, hence its classification as a metalloid.

Germanium is relatively stable at room temperature. It forms a thin, protective layer of germanium dioxide (GeO₂) when exposed to air at elevated temperatures, which prevents further oxidation. This oxide layer is transparent and stable, providing good corrosion resistance under normal conditions.

Germanium reacts slowly with oxygen at room temperature but oxidizes more readily when heated above 600-700 °C, forming germanium(IV) oxide: Ge + O₂ → GeO₂. This oxide is amphoteric, showing both acidic and basic properties, though it is predominantly acidic and dissolves more readily in bases than in acids.

Germanium is relatively resistant to dilute acids at room temperature but dissolves slowly in hot concentrated sulfuric acid and more rapidly in aqua regia (a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids): 3Ge + 4HNO₃ + 18HCl → 3GeCl₄ + 4NO + 8H₂O. Unlike silicon, germanium does not dissolve in hydrofluoric acid.

With strong bases, germanium reacts to form germanates, particularly when molten: Ge + 2OH⁻ + 2H₂O → GeO₃²⁻ + 2H₂. This behavior parallels that of silicon and demonstrates the amphoteric nature of germanium, though it is less reactive with bases than silicon.

Germanium reacts with halogens to form tetrahalides: Ge + 2X₂ → GeX₄ (where X = F, Cl, Br, I). These reactions occur readily, especially at elevated temperatures. Germanium tetrachloride (GeCl₄) is a particularly important compound, used in fiber optics and as a precursor in semiconductor manufacturing.

Germanium forms various compounds with other elements including sulfides (GeS, GeS₂), nitrides, and organogermanium compounds. It can also form alloys with many metals and is particularly important in silicide and germanide formations used in modern microelectronics.

Germanium is synthesized in stars through multiple nucleosynthesis pathways. It is primarily produced during silicon burning in the final stages of massive star evolution, as well as through the slow neutron capture process (s-process) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars and during type II supernova explosions through the rapid neutron capture process (r-process).

The five stable isotopes of germanium (\(\,^{70}\mathrm{Ge}\), \(\,^{72}\mathrm{Ge}\), \(\,^{73}\mathrm{Ge}\), \(\,^{74}\mathrm{Ge}\), and \(\,^{76}\mathrm{Ge}\)) are produced through these stellar processes and dispersed into the interstellar medium during stellar mass loss and supernova events. The isotopic ratios of germanium measured in meteorites provide valuable constraints on the contributions of different nucleosynthesis processes in the early solar system.

The cosmic abundance of germanium is approximately 50 atoms per million silicon atoms, making it relatively rare compared to lighter elements. This scarcity reflects the challenges in synthesizing intermediate-mass nuclei (A ≈ 70-76) during stellar nucleosynthesis, as this mass region lies near the peak of nuclear binding energy per nucleon.

Germanium plays a crucial role in modern astroparticle physics. Ultra-pure germanium detectors are extensively used in experiments searching for dark matter particles through their potential interactions with atomic nuclei. Experiments such as CDMS (Cryogenic Dark Matter Search) and EDELWEISS use germanium crystals cooled to millikelvin temperatures to detect rare interactions with hypothetical WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles).

The isotope \(\,^{76}\mathrm{Ge}\) is particularly significant in neutrino physics. Although effectively stable for practical purposes, it is theoretically capable of undergoing neutrinoless double beta decay, a hypothetical process that would demonstrate that neutrinos are their own antiparticles (Majorana particles). Experiments like GERDA and LEGEND use enriched ⁷⁶Ge to search for this extremely rare decay, which would have profound implications for particle physics and cosmology.

Spectral lines of ionized germanium (Ge II, Ge III, Ge IV) have been detected in the spectra of certain stellar atmospheres and in supernova remnants. The analysis of these lines helps astronomers understand stellar composition, nucleosynthesis yields, and the chemical evolution of galaxies over cosmic time.

N.B. :

Germanium is present in the Earth's crust at a concentration of approximately 0.00015% by mass (1.5 ppm), making it a rare element, less abundant than silver. It does not occur in concentrated deposits but is widely dispersed in small quantities. Germanium is typically associated with zinc ores (sphalerite), certain coal deposits, and to a lesser extent with copper and lead ores.

Germanium is primarily extracted as a byproduct of zinc refining, where it concentrates in flue dusts and residues during zinc smelting. Coal fly ash from certain coal types also represents an important source. Global primary germanium production is approximately 120-130 tons per year, with China dominating production (≈ 60%), followed by Canada, Russia, Finland, and the United States.

Recycling of germanium is economically viable and environmentally important. Germanium can be recovered from scrap fiber optics, infrared optical systems, and end-of-life electronics. The recycling rate is estimated at approximately 30% of total consumption, significantly higher than many other specialty metals. This relatively high recycling rate helps offset the limited primary production and reduces environmental impacts.

The demand for germanium fluctuates with technological trends but has grown steadily, driven by fiber optic communications, infrared optics, and renewable energy applications. Germanium is classified as a critical raw material by the European Union and appears on similar strategic material lists in other regions due to its essential role in key technologies, limited primary sources, and concentrated global production. Supply security concerns have stimulated research into germanium substitution and more efficient recycling methods.