Arsenic has been known since antiquity, long before its recognition as a chemical element. Arsenic compounds, particularly yellow arsenic sulfide (orpiment, As₂S₃) and red arsenic sulfide (realgar, As₄S₄), were used as pigments and poisons as early as the time of the Greeks and Romans. The word arsenic comes from the Greek arsenikon, itself derived from the Persian zarnikh, meaning yellow pigment.

In the Middle Ages, alchemists were familiar with arsenic in the form of arsenic trioxide (As₂O₃), also known as white arsenic. In 1250, the German scholar Albertus Magnus (1200-1280) was the first to isolate metallic arsenic by heating arsenic trioxide with soap. This reduction method allowed the element to be obtained in its elementary form.

However, it was the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742-1786) who, in 1775, demonstrated that arsenic was a true chemical element and not a compound. He established its elemental nature by studying its properties and chemical reactions. Arsenic was officially recognized as an element at the end of the 18th century.

The history of arsenic is closely linked to criminal poisoning. During the 17th and 18th centuries, odorless and tasteless arsenic trioxide was widely used as a poison, to the point of being nicknamed inheritance powder in reference to the inheritances it allowed to accelerate. The development of the Marsh test in 1836 by the British chemist James Marsh finally made it possible to detect the presence of arsenic in biological tissues, revolutionizing forensic medicine.

Arsenic (symbol As, atomic number 33) is a metalloid in group 15 of the periodic table. Its atom has 33 protons, usually 42 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{75}\mathrm{As}\)), and 33 electrons with the electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p³.

Arsenic exhibits several allotropic forms, the most stable being gray arsenic (α form), a shiny metallic solid with a steel-gray color. This form has a rhombohedral crystalline structure with a density of 5.73 g/cm³. Gray arsenic is a semiconductor that becomes superconducting at very low temperatures.

There is also yellow arsenic (γ form), an unstable molecular form composed of tetrahedral As₄ molecules, similar to white phosphorus. This form, obtained by rapid condensation of arsenic vapor, is extremely reactive and spontaneously transforms into gray arsenic at room temperature.

Black arsenic (β form), obtained by slow sublimation of gray arsenic, has an amorphous structure and lies between the yellow and gray forms in terms of reactivity.

Arsenic does not melt at atmospheric pressure but sublimes directly at 615 °C (888 K), passing from solid to gaseous state without becoming liquid. Under high pressure (about 28 atm), arsenic can melt at 817 °C. This sublimation property has historically been used to purify arsenic.

The sublimation point of arsenic: 888 K (615 °C) at atmospheric pressure.

The melting point of arsenic: 1,090 K (817 °C) at 28 atmospheres.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic-75 — \(\,^{75}\mathrm{As}\,\) | 33 | 42 | 74.921595 u | 100 % | Stable | Only stable isotope of arsenic. Has a nuclear magnetic moment used in NMR. |

| Arsenic-73 — \(\,^{73}\mathrm{As}\,\) | 33 | 40 | 72.923825 u | Synthetic | ≈ 80.3 days | Radioactive (electron capture). Used in biomedical research as a tracer. |

| Arsenic-74 — \(\,^{74}\mathrm{As}\,\) | 33 | 41 | 73.923929 u | Synthetic | ≈ 17.8 days | Radioactive (β⁺, electron capture). Positron emitter used in PET for medical imaging. |

| Arsenic-76 — \(\,^{76}\mathrm{As}\,\) | 33 | 43 | 75.922394 u | Synthetic | ≈ 26.3 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Produced in nuclear reactors, used in research. |

| Arsenic-77 — \(\,^{77}\mathrm{As}\,\) | 33 | 44 | 76.920648 u | Synthetic | ≈ 38.8 hours | Radioactive (β⁻). Used in targeted radiotherapy and as a tracer in agronomy. |

N.B. :

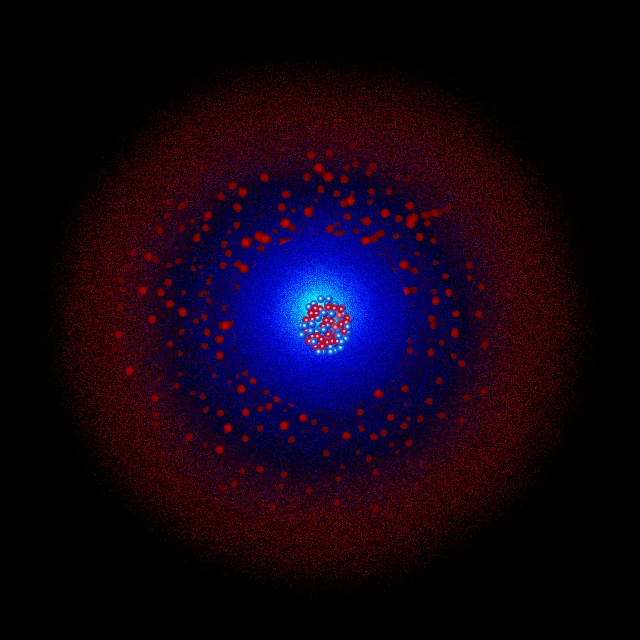

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Arsenic has 33 electrons distributed over four electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p³, or simplified: [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p³. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(5).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. The presence of the complete 3d subshell is characteristic of post-transition elements and significantly influences the properties of arsenic.

N Shell (n=4): contains 5 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p³. These five electrons are the valence electrons of arsenic.

The 5 electrons in the outer shell (4s² 4p³) are the valence electrons of arsenic. This configuration explains its varied chemical properties:

The most common oxidation state of arsenic is +3, where it loses its three 4p³ electrons to form the As³⁺ ion. This configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² has the inert pair effect. Arsenic(III) compounds include arsenic trioxide (As₂O₃) and arsenic trichloride (AsCl₃).

The oxidation state +5 is also important, where arsenic loses all its valence electrons to form As⁵⁺ with the configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰. Arsenic(V) compounds include arsenic acid (H₃AsO₄) and arsenic pentoxide (As₂O₅). This state is less stable than +3 and has oxidizing properties.

Negative oxidation states also exist: -3 in metallic arsenides such as GaAs (gallium arsenide), where arsenic gains three electrons to complete its valence shell, forming As³⁻ with the configuration [Ar] 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶.

Arsenic can also exhibit oxidation states of 0 (metallic arsenic), +1, and +2, although these are rare and unstable. The chemistry of arsenic is dominated by the +3 and +5 forms, reflecting the stability of the inert 4s² pair and the possibility of using all valence electrons.

Gray arsenic is relatively stable in air at room temperature, slowly forming a thin oxide layer that protects it from further oxidation. This passivation gives it moderate resistance to atmospheric corrosion. However, yellow arsenic is extremely reactive and oxidizes spontaneously in air, producing light (chemiluminescence).

At high temperatures, arsenic burns in oxygen with a pale blue flame, forming arsenic trioxide (As₂O₃), which is released as characteristic white smoke: 4As + 3O₂ → 2As₂O₃. This reaction produces a typical garlic odor due to volatile arsenic compounds.

Arsenic reacts with oxidizing acids to form arsenic(III) or (V) compounds. With concentrated nitric acid, it forms arsenic acid: As + 5HNO₃ → H₃AsO₄ + 5NO₂ + H₂O. Arsenic is relatively resistant to dilute non-oxidizing acids but reacts slowly with concentrated hydrochloric acid.

With strong bases, arsenic dissolves to form arsenates or arsenites depending on the conditions: 2As + 6NaOH + 3O₂ → 2Na₃AsO₄ + 3H₂O (formation of arsenate) or 2As + 6NaOH → 2Na₃AsO₃ + 3H₂ (in the absence of oxygen, formation of arsenite).

Arsenic reacts directly with most halogens to form trihalides (AsX₃) or pentahalides (AsX₅): 2As + 3X₂ → 2AsX₃ (where X = F, Cl, Br, I). The trifluoride (AsF₃) and pentafluoride (AsF₅) are particularly stable.

Arsenic also forms compounds with metals (arsenides) and with hydrogen. Arsine (AsH₃) is an extremely toxic gas, even more dangerous than elemental arsenic. It is used in the semiconductor industry for doping and the manufacture of III-V compounds.

Arsenic is synthesized in stars through several nucleosynthesis processes. It is mainly formed during the explosive burning of silicon in Type II supernovae, as well as through slow neutron capture processes (s-process) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars and rapid neutron capture processes (r-process) during cataclysmic events.

The only stable isotope of arsenic (\(\,^{75}\mathrm{As}\)) is produced by these mechanisms and dispersed into the interstellar medium during stellar explosions. The abundance of arsenic in primitive meteorites provides information on the nucleosynthesis conditions in the primordial solar system and on planetary formation processes.

The cosmic abundance of arsenic is very low, about 8×10⁻¹⁰ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This rarity reflects the difficulties in synthesizing nuclei in this atomic mass region (A ≈ 75) and the fact that arsenic has an odd number of protons and neutrons, making it less stable than its even-numbered neighbors.

Spectral lines of ionized arsenic (As II, As III) have been detected in the spectra of certain hot stars and peculiar stellar objects such as chemically peculiar stars. The study of these lines helps understand stellar chemical enrichment and the chemical evolution of galaxies.

Arsenic also plays a potential role in astrobiology. Some terrestrial bacteria can use arsenic in their metabolism, either by reducing arsenate (As⁵⁺) to arsenite (As³⁺) to obtain energy, or by incorporating arsenic into biomolecules. This ability has raised questions about the possibility of arsenic-based life forms rather than phosphorus-based ones in arsenic-rich extraterrestrial environments.

N.B. :

Arsenic is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.00018% by mass (1.8 ppm), making it a relatively rare element. It does not form its own ores but is found associated with other elements, mainly in metal sulfides such as arsenopyrite (FeAsS), realgar (As₄S₄), orpiment (As₂S₃), and in copper, lead, and gold ores.

Arsenic is mainly extracted as a byproduct of copper and lead ore processing. Global arsenic production is about 33,000 tons per year, mainly in China (≈ 65%), Morocco, Russia, and Chile. Arsenic is generally marketed as white arsenic trioxide.

Due to its high toxicity, the use of arsenic is strictly regulated in most countries. WHO standards limit the concentration of arsenic in drinking water to 10 μg/L (10 parts per billion). Chronic exposure to arsenic can cause serious health problems, including skin, lung, and bladder cancers, as well as cardiovascular and neurological diseases.

Arsenic poisoning remains a major public health problem in some regions of the world, particularly in Bangladesh and India, where groundwater naturally contains high levels of arsenic. Millions of people are exposed to this natural contamination, which represents one of the greatest environmental health disasters in modern history.