Neodymium is synthesized in stars by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars and the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Neodymium shows a balanced contribution from these two processes, with about 40-50% from the s-process and 50-60% from the r-process, making it an excellent tracer for studying the relative contributions of these two nucleosynthesis mechanisms.

The cosmic abundance of neodymium is about 8.3×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about 15 times less abundant than cerium but 4-5 times more abundant than praseodymium in the universe. This relatively high abundance among lanthanides is explained by the presence of several stable isotopes (seven in total) with favorable nuclear configurations. The isotope Nd-142 has a magic number of neutrons (82), giving it exceptional stability.

The spectral lines of neutral (Nd I) and ionized (Nd II) neodymium are observable in stellar spectra, particularly in cool G, K, and M type stars. Neodymium is used as an important tracer of galactic chemical enrichment. The neodymium/iron ratio in metal-poor stars helps constrain the chemical evolution of the Galaxy and the relative contributions of different types of supernovae to the enrichment in heavy elements.

The isotopic ratios of neodymium in primitive meteorites reveal anomalies compared to terrestrial values, testifying to the diversity of nucleosynthesis sources in the early solar system. Some presolar grains extracted from meteorites show extreme enrichments in specific neodymium isotopes, allowing direct identification of material from individual AGB stars or supernovae. These isotopic anomalies are powerful tools for reconstructing the history of the solar system's formation and understanding mixing processes in the protoplanetary disk.

Neodymium takes its name from the Greek words neos (new) and didymos (twin), meaning "new twin". This name was chosen by its discoverer to indicate that it was a new element separated from didymium, accompanying praseodymium, the "green twin". Neodymium is distinguished by the characteristic purple-pink color of its salts, contrasting with the green of praseodymium.

In 1885, the Austrian chemist Carl Auer von Welsbach (1858-1929) achieved the remarkable feat of separating didymium into two distinct elements: praseodymium and neodymium. This separation was accomplished by repeated fractional crystallizations (several hundred iterations) of rare earth nitrates, demonstrating extraordinary patience and experimental skill. Welsbach observed that successive fractions produced salts of different colors, with praseodymium giving green crystals and neodymium giving pink crystals.

The isolation of pure neodymium metal presented a considerable challenge that was only resolved in the early 20th century. Early attempts at electrolyzing molten salts produced neodymium contaminated with praseodymium and other lanthanides. It was not until the development of ion exchange techniques in the 1940s-1950s, stimulated by the Manhattan Project, that high-purity separation of rare earths became economically viable. Modern solvent extraction methods now allow the production of neodymium with purity exceeding 99.9%.

Neodymium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 38 ppm, making it the 28th most abundant element on Earth, more abundant than cobalt, lithium, or lead. It is the second most abundant light rare earth after cerium. The main minerals containing neodymium are bastnäsite ((Ce,La,Pr,Nd)CO₃F), where neodymium accounts for about 12-15% of the rare earth content, and monazite ((Ce,La,Pr,Nd,Th)PO₄), where it accounts for 15-20%.

Global production of neodymium oxides is about 25,000 to 30,000 tons per year. China dominates massively with about 85-90% of global production, followed by the United States (Mountain Pass, California), Australia (Mount Weld), and Myanmar. This extreme geographical concentration makes neodymium one of the most strategically critical materials in the world, indispensable for the energy transition and defense technologies.

Neodymium metal is produced mainly by calcium reduction of neodymium oxide (Nd₂O₃) at high temperature in an inert atmosphere, or by electrolysis of molten neodymium fluoride in a molten salt bath. Global annual production of neodymium metal is about 7000 to 9000 tons. Recycling of neodymium from used magnets (hard drives, electric motors) remains limited, accounting for about 1-2% of total supply, although efforts are intensifying significantly due to supply concerns and rising prices.

Neodymium (symbol Nd, atomic number 60) is the fourth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the f-block rare earths of the periodic table. Its atom has 60 protons, usually 82 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{142}\mathrm{Nd}\)) and 60 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁴ 6s².

Neodymium is a shiny metal with a silvery-white color and a slight golden tint. It oxidizes rapidly in air, forming an oxide layer that gradually disintegrates, continuously exposing fresh metal. Neodymium crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure at room temperature, transitioning to a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure at about 863 °C. Neodymium is relatively soft and malleable, can be cut with a knife, and has moderate ductility allowing it to be rolled into thin sheets.

Neodymium melts at 1021 °C (1294 K) and boils at 3074 °C (3347 K). Its density is 7.01 g/cm³, slightly higher than that of iron. Neodymium is a good conductor of electricity and heat, with electrical conductivity about 16 times lower than that of copper. Neodymium exhibits remarkable magnetic properties: it is paramagnetic at room temperature and becomes antiferromagnetic below 19 K, with a complex magnetic structure.

Neodymium is a highly reactive metal, particularly in divided form. It oxidizes rapidly in humid air and easily ignites when heated or in the form of fine shavings. Neodymium reacts vigorously with water, producing neodymium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Neodymium metal must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere (argon) to prevent oxidation. Its reactivity is typical of light lanthanides and comparable to that of praseodymium.

Melting point of neodymium: 1294 K (1021 °C).

Boiling point of neodymium: 3347 K (3074 °C).

Neodymium is paramagnetic at room temperature and becomes antiferromagnetic below 19 K.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neodymium-142 — \(\,^{142}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 82 | 141.907723 u | ≈ 27.152 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope of neodymium. Magic number of neutrons (82). |

| Neodymium-143 — \(\,^{143}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 83 | 142.909814 u | ≈ 12.174 % | Stable | Stable isotope, important product of the r-process. |

| Neodymium-144 — \(\,^{144}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 84 | 143.910087 u | ≈ 23.798 % | ≈ 2.29×10¹⁵ years | Radioactive (α), extremely long half-life, practically stable. Second most abundant isotope. |

| Neodymium-145 — \(\,^{145}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 85 | 144.912574 u | ≈ 8.293 % | Stable | Minor stable isotope of neodymium. |

| Neodymium-146 — \(\,^{146}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 86 | 145.913117 u | ≈ 17.189 % | Stable | Stable isotope representing about 17% of natural neodymium. |

| Neodymium-148 — \(\,^{148}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 88 | 147.916893 u | ≈ 5.756 % | Stable | Minor stable isotope, product of the r-process. |

| Neodymium-150 — \(\,^{150}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 90 | 149.920891 u | ≈ 5.638 % | ≈ 6.7×10¹⁸ years | Radioactive (double β⁻), extremely long half-life, practically stable. |

| Neodymium-147 — \(\,^{147}\mathrm{Nd}\,\) | 60 | 87 | 146.916100 u | Synthetic | ≈ 10.98 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Fission product, used as a tracer in medical and industrial research. |

N.B.:

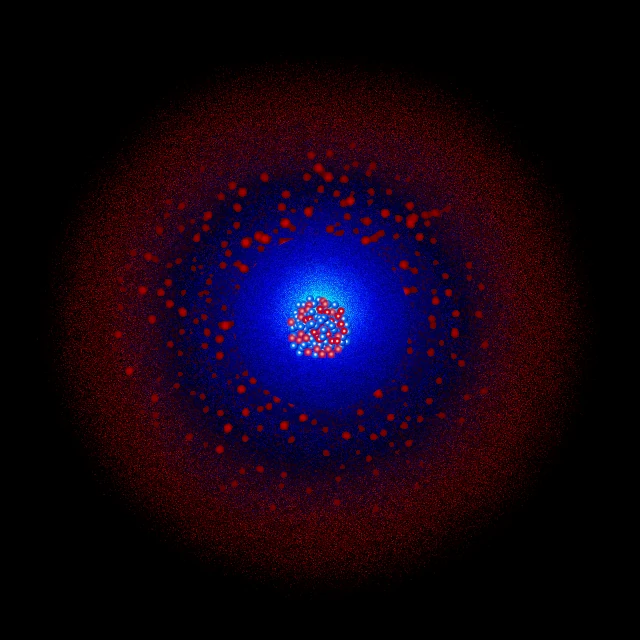

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Neodymium has 60 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration is [Xe] 4f⁴ 6s², typical of lanthanides where the 4f subshell is progressively filled. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(22) P(2), or fully: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N Shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable and complete structure.

O Shell (n=5): contains 22 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f⁴ 5d⁰. The four 4f electrons characterize the chemistry of neodymium.

P Shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of neodymium.

Neodymium effectively has 6 valence electrons: four 4f⁴ electrons and two 6s² electrons. The almost exclusive oxidation state is +3, characteristic of all lanthanides, where neodymium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Nd³⁺ ion with the configuration [Xe] 4f³. This Nd³⁺ ion is responsible for the characteristic purple-pink color of neodymium salts and solutions.

The +3 state appears in virtually all neodymium compounds: neodymium(III) oxide (Nd₂O₃), neodymium(III) chloride (NdCl₃), neodymium(III) nitrate (Nd(NO₃)₃), and all complex salts. The chemistry of neodymium is essentially the chemistry of the Nd³⁺ ion, with its unique optical and magnetic properties derived from the 4f³ configuration.

Oxidation states +2 and +4 have been synthesized under extreme conditions (solid-phase halides, cryogenic matrices), but these compounds are extraordinarily unstable and have no practical relevance. Unlike neighboring cerium, neodymium does not form stable compounds in the +4 state. The chemistry of neodymium is therefore essentially monovalent, dominated by the +3 state.

Neodymium is very reactive with oxygen and oxidizes rapidly in air, forming a blue-gray layer of neodymium(III) oxide (Nd₂O₃) that cracks and flakes, continuously exposing fresh metal to oxidation. Complete oxidation of a neodymium metal sample in air can occur within a few days. At high temperatures, neodymium easily ignites in air and burns with a bright white flame: 4Nd + 3O₂ → 2Nd₂O₃. Neodymium in shavings or fine powder form is pyrophoric and spontaneously ignites at room temperature.

Neodymium reacts slowly with cold water but rapidly with hot water, producing purple-pink neodymium(III) hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas: 2Nd + 6H₂O → 2Nd(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. This reaction accelerates considerably with temperature and can become vigorous with boiling water. Neodymium(III) hydroxide easily precipitates from aqueous solutions as a pale pink gelatinous solid.

Neodymium reacts vigorously with all halogens to form colored trihalides: 2Nd + 3Cl₂ → 2NdCl₃ (purple), 2Nd + 3Br₂ → 2NdBr₃ (purple), 2Nd + 3I₂ → 2NdI₃ (green). Neodymium dissolves easily in acids, even diluted ones, with the release of hydrogen: 2Nd + 6HCl → 2NdCl₃ + 3H₂↑, producing characteristic pink solutions of Nd³⁺.

Neodymium reacts with sulfur to form neodymium sulfide (Nd₂S₃), with nitrogen at high temperature to form nitride (NdN), with carbon to form carbide (NdC₂), and with hydrogen to form hydride (NdH₂ or NdH₃). Neodymium also forms many organometallic compounds and coordination complexes, exploited in organic synthesis as polymerization catalysts.

The intense purple-pink color of neodymium(III) compounds comes from f-f electronic transitions within the 4f³ configuration. These transitions produce characteristic absorption bands in the visible spectrum, particularly in the yellow and green regions, preferentially transmitting red and violet. Neodymium-doped glass exhibits remarkable optical behavior: it appears purple in transmitted incandescent light but blue in reflected light, a phenomenon called dichroism. This unique optical property is exploited in neodymium lasers and protective glasses.

The dominant application of neodymium, accounting for about 75-85% of global consumption, is its use in Nd₂Fe₁₄B (neodymium-iron-boron) type permanent magnets, independently discovered in 1982 by General Motors and Sumitomo Special Metals. These magnets have the highest maximum energy product (BHmax) of all commercial permanent magnets, reaching 400-460 kJ/m³, about 10 times higher than traditional ferrite magnets and twice that of samarium-cobalt magnets.

The typical composition of an Nd-Fe-B magnet is about 32-35% neodymium and praseodymium combined (usually 25-30% Nd, 5-10% Pr), 1-2% dysprosium or terbium (to improve thermal stability), less than 1% boron, and the rest iron. The main magnetic phase Nd₂Fe₁₄B has a tetragonal structure and a Curie temperature of about 312 °C. The coercive field can reach 1000-2000 kA/m, allowing the magnets to resist demagnetization even under severe conditions.

Nd-Fe-B magnets are absolutely essential for the energy transition and modern technologies. An electric vehicle contains 1-2 kg of neodymium in its motor, an offshore 3 MW wind turbine contains 200-600 kg of neodymium in its direct-drive generator. Hard drives use tiny Nd-Fe-B magnets to position read heads with nanometric precision. Guided weapon systems, military drones, torpedoes, and submarines critically depend on compact Nd-Fe-B magnet motors. This strategic importance combined with China's dominance in production makes neodymium one of the most geopolitically sensitive materials in the world.

Neodymium is the most important doping ion for solid-state lasers, particularly in the yttrium-aluminum garnet (YAG) matrix forming the Nd:YAG laser. Invented in 1964, the Nd:YAG laser emits primarily at 1064 nm in the near-infrared, with remarkable efficiency and excellent beam quality. The typical neodymium concentration is 1% atomic (about 1.4×10²⁰ Nd³⁺ ions/cm³), optimizing laser gain while minimizing deleterious effects such as line broadening.

Nd:YAG lasers are used for metal cutting and welding, industrial marking, precision drilling, and surface treatment. In medicine, they are used for ophthalmic surgery (YAG capsulotomy), lithotripsy (kidney stone destruction), diabetic retina treatment, hair removal, and various dermatological procedures. Nd:YAG lasers can be frequency doubled to produce green light at 532 nm, used in green laser pointers, light shows, and some medical applications.

Beyond YAG, neodymium is also doped into other crystalline matrices such as YVO₄ (yttrium vanadate), YLF (lithium-yttrium fluoride), and various phosphate or silicate glasses to create fiber lasers and optical amplifiers. Neodymium-doped glasses are used in laser rangefinders, atmospheric lidar systems, and inertial confinement fusion applications where massive Nd:glass lasers deliver megajoules of energy to compress deuterium-tritium targets.

Neodymium is used as a dopant in glasses to create optical filters with remarkable selective absorption properties. Neodymium-doped glass strongly absorbs yellow wavelengths (around 580-600 nm), corresponding to sodium emission lines, while transmitting blue, red, and near-infrared. This selective absorption significantly reduces glare caused by sodium lighting or sodium-rich flames.

Didymium glasses (neodymium-praseodymium mixture) are used for protective glasses for glassblowers, metallurgists, and welders working with sodium-rich flames. In jewelry and artistic glassmaking, neodymium-doped glass produces fascinating color effects: it appears purple-blue in transmitted incandescent light but pink-red in fluorescent or daylight, creating spectacular dichroism. This property is also exploited in high-end sunglasses and some automotive glasses to improve contrast and reduce eye strain.

Neodymium and its compounds have low toxicity, similar to other light lanthanides. Soluble neodymium compounds can cause skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation upon direct exposure. Inhalation of neodymium dust can cause transient pulmonary irritation, although no specific chronic pulmonary disease related to neodymium has been documented. Neodymium salts ingested orally are poorly absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract and are mainly eliminated in feces.

Toxicological studies in animals indicate that absorbed neodymium accumulates mainly in the liver, spleen, and bone skeleton. At high doses (above 100 mg/kg), neodymium can cause moderate hepatic toxicity and disrupt calcium metabolism. However, significant human exposures remain rare outside specialized industrial environments. Neodymium does not show substantial bioaccumulation in food chains and is relatively quickly metabolized or eliminated. No carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic effects have been demonstrated in available studies.

Environmental concerns associated with neodymium primarily relate to rare earth mining, which generates significant volumes of toxic and radioactive waste. The extraction of one ton of rare earth oxides typically produces 2000 tons of mining waste, 200 m³ of acidic contaminated water, and can release radioactive elements such as thorium and uranium naturally present in monazite ores. Rare earth mining sites in China have caused significant environmental pollution, contaminating soils, groundwater, and waterways with heavy metals and radioactive substances.

Occupational exposure to neodymium mainly occurs in rare earth refining industries, magnet manufacturing, and optical polishing. Occupational exposure standards for neodymium compounds are not specifically established in most jurisdictions, but general recommendations for soluble rare earth compounds typically set exposure limits at 5-10 mg/m³ for respirable dust. Neodymium concentrations in soils near rare earth mines can reach several hundred ppm, 10-20 times natural background levels.

Recycling of neodymium from used magnets is technically possible but economically challenging due to high costs of dismantling, separation, and purification. Nd-Fe-B magnets are often strongly integrated into complex assemblies (motors, hard drives) and can be oxidized or contaminated. Current recycling rates remain very low (1-2%), but several innovative processes are under development: selective chemical dissolution, direct melting for magnet remanufacturing, solvent extraction of oxides, and hydrometallurgical treatment. Substantially increasing neodymium recycling rates is crucial for the long-term sustainability of the energy transition and to reduce dependence on China-dominated primary supplies.