Lanthanum is an element produced mainly by the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. It is the first element in the lanthanide series (rare earths), and its synthesis marks the beginning of the filling of the 4f electronic subshell. It is also produced in significant quantities by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during explosive events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. The relative contribution of the s and r processes to its solar abundance is about 70% for the s-process and 30% for the r-process, making it a good tracer of nucleosynthesis conditions.

The cosmic abundance of lanthanum is about 2.0×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it significantly more abundant than heavy elements such as gold or platinum, but less than iron. It is one of the most abundant rare earths, along with cerium and neodymium. Its presence in stellar spectra is used to determine the abundance of rare earths and the metallicity of stars, especially in old stars rich in s-process elements.

In Earth sciences, the abundance ratios of rare earths, with lanthanum as a reference element, are powerful diagnostic tools. The "spectrum" of rare earths (chondrite-normalized diagram) reveals geological processes such as partial melting, fractional crystallization, or meteoritic alteration. Lanthanum, being the lightest, is relatively more incompatible (prefers the magmatic liquid) than its heavier counterparts. This systematic variation allows tracing the history of rocks and planets.

Chondritic meteorites, considered as the primitive building blocks of the solar system, have a rare earth abundance almost identical to that of the Sun, with lanthanum serving as a calibration point. Anomalies in rare earths in some differentiated meteorites (such as eucrites) testify to early planetary differentiation processes. Isotopic studies of barium and lanthanum also help understand the chronology of presolar nucleosynthesis.

Lanthanum takes its name from the ancient Greek verb λανθάνω (lanthánō), which means "to be hidden, to escape notice". This name was chosen by its discoverer, Carl Gustaf Mosander, in 1839, because the element was "hidden" (or difficult to separate) in a cerite mineral, from which cerium had already been extracted. This choice reflects the historical difficulty in isolating rare earths, which are very similar chemically to each other.

In 1839, the Swedish chemist Carl Gustaf Mosander (1797-1858) was working on cerium oxide, supposed to be pure. By treating cerium nitrate with a dilute acid and heating it, he obtained a new earthy-colored oxide, which he named "lanthana". He had thus isolated lanthanum, discovering at the same time that the "cerium" of the time was actually a mixture of at least two elements: cerium and lanthanum. This discovery marked the beginning of the systematic separation of rare earths.

The isolation of pure lanthanum metal was a difficult task due to its high reactivity and similarity to other rare earths. Relatively pure metal was first produced in 1923 by H. Kremers and R. Stevens, by electrolysis of a molten mixture of chlorides. It was only with the development of ion exchange and solvent extraction techniques in the mid-20th century that the production of high-purity lanthanum became industrial.

Lanthanum does not exist in its native state. It is present in many rare earth minerals, mainly:

The main producing countries are China (which largely dominates production and refining), the United States (Mountain Pass mine), Australia, and Russia. Annual production is on the order of several tens of thousands of tons (in oxide equivalent). Although classified among the "rare earths", lanthanum is relatively abundant in the Earth's crust (about 35 ppm), more than lead or tin. Its price is moderate for a rare earth, but subject to fluctuations depending on Chinese export policy and technological demand.

Lanthanum (symbol La, atomic number 57) is an inner transition element, traditionally placed as the first element of the lanthanide series (rare earths) in the periodic table, although its electronic configuration does not have a 4f electron (this subshell is empty). It belongs to group 3 with scandium and yttrium. Its atom has 57 protons, usually 82 neutrons (for the stable isotope \(^{139}\mathrm{La}\)), and 57 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 5d¹ 6s². This configuration with a 5d electron distinguishes it from the following lanthanides that fill the 4f subshell.

Lanthanum is a silvery-white, malleable, ductile, and fairly soft metal. It is very reactive and oxidizes rapidly in air.

Lanthanum has a melting point of 918 °C (1191 K) and a boiling point of 3464 °C (3737 K). It exists in two allotropic forms: the α form (double hexagonal close-packed) stable up to 310 °C, and the β form (face-centered cubic) stable from 310 °C to the melting point. This transition affects its mechanical and electrical properties.

Lanthanum is a very electropositive and reactive metal, similar to alkaline earth metals. It oxidizes rapidly in air to form La₂O₃. It reacts with water (even cold) to release hydrogen and form La(OH)₃. It dissolves easily in most dilute mineral acids (HCl, H₂SO₄, HNO₃) to form the corresponding La³⁺ salts and release hydrogen (except with HNO₃ where nitrogen oxides are formed).

Density: 6.162 g/cm³.

Melting point: 1191 K (918 °C).

Boiling point: 3737 K (3464 °C).

Crystal structure (at 20°C): Double hexagonal close-packed (DH).

Main oxidation state: +3.

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 5d¹ 6s².

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanthanum-138 — \(^{138}\mathrm{La}\) | 57 | 81 | 137.907112 u | ≈ 0.090 % | 1.02×10¹¹ years | Primordial radioactive. Decays by electron capture (66%) to \(^{138}\mathrm{Ba}\) and by β⁻ decay (34%) to \(^{138}\mathrm{Ce}\). Isotope used in La-Ba and La-Ce geochronology. |

| Lanthanum-139 — \(^{139}\mathrm{La}\) | 57 | 82 | 138.906353 u | ≈ 99.910 % | Stable | Stable and major isotope. Represents almost all natural lanthanum. Used as a reference for isotopic measurements. |

N.B.:

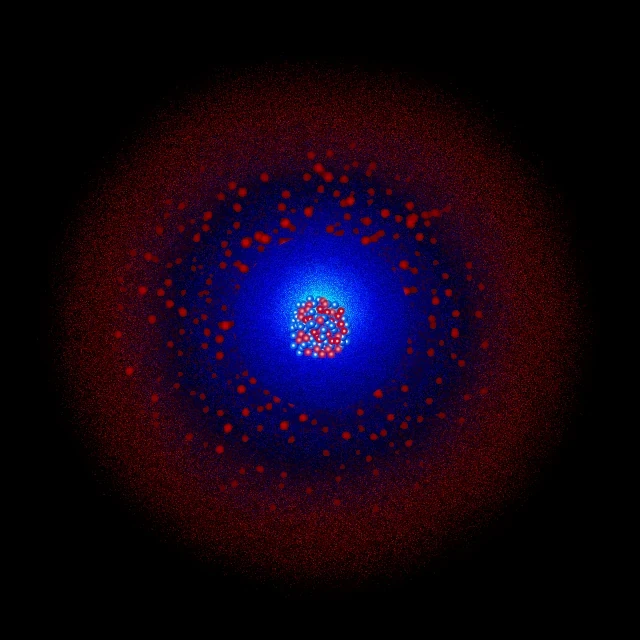

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Lanthanum has 57 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 5d¹ 6s² has a peculiarity: the 4f subshell is empty (0 electrons), while a single electron occupies the 5d subshell, with the two electrons of the 6s shell. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(9) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹ 6s². This atypical configuration (5d¹ instead of 4f¹) makes it a special case among the lanthanides.

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰). The 4f subshell is empty.

O shell (n=5): contains 9 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹).

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons (6s²).

Lanthanum has 3 valence electrons: the two 6s² electrons and the 5d¹ electron. It easily loses these three electrons to reach the stable configuration of xenon (Xe), which explains its unique and very stable oxidation state: +3 (La³⁺). La³⁺ ions are colorless (no f electrons) and have a large ionic radius, which strongly influences their coordination chemistry and geochemical behavior (strong incompatible character).

Unlike some lanthanides, lanthanum practically does not exhibit +2 or +4 oxidation states, as the La²⁺ (4f¹) or La⁴⁺ (4f⁻¹) configuration would be very unstable. Its chemistry is therefore dominated by the trivalent cation La³⁺, which forms typical ionic compounds (oxide, hydroxide, halides, salts).

Lanthanum metal oxidizes rapidly in air at room temperature, forming a layer of La₂O₃. When heated, it burns vigorously to form the same oxide: 4La + 3O₂ → 2La₂O₃. La₂O₃ is a white basic oxide that reacts with water to form La(OH)₃ and easily absorbs carbon dioxide from the air to form carbonate.

Lanthanum reacts with cold water, and more rapidly with hot water, to release hydrogen and form insoluble La(OH)₃: 2La + 6H₂O → 2La(OH)₃ + 3H₂. It dissolves rapidly in dilute mineral acids (HCl, H₂SO₄, HNO₃) to form the corresponding La³⁺ salts and release hydrogen (except with HNO₃ where nitrogen oxides are formed).

Lanthanum reacts with all halogens to form trihalides: 2La + 3X₂ → 2LaX₃ (X = F, Cl, Br, I). Lanthanum fluoride LaF₃ is particularly insoluble in water. It also reacts with nitrogen at high temperature to form LaN, with carbon to form LaC₂, with sulfur to form La₂S₃, and with hydrogen to form LaH₂/LaH₃.

This is the largest application of lanthanum. Lanthanum oxide (La₂O₃) is added to zeolites (zeolite Y) used in fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) units in refineries. Its role is twofold:

Without lanthanum, the efficiency of petroleum refining would be significantly reduced.

Lanthanum-based alloys (such as LaNi₅ or more complex rare earth alloys, "mischmetal") constitute the material of the negative electrode (anode) of NiMH batteries. These alloys reversibly absorb and desorb large amounts of hydrogen. NiMH batteries, safer and more environmentally friendly than Ni-Cd, have equipped generations of hybrid vehicles (such as the Toyota Prius), cordless tools, and electronic devices. Although supplanted by Li-ion in many areas, they remain important for certain applications.

LaNi₅ alloys are also studied for solid hydrogen storage due to their ability to absorb it. In addition, lanthanum oxide is used in catalysts for hydrogen production by steam reforming of methane or biofuels.

Lanthanum oxide (La₂O₃) is an essential component of certain optical glasses called "high rare earth content" or "lanthanum glasses". These glasses have a very high refractive index and a low dispersion (Abbe number). These properties allow the manufacture of high-performance, lightweight, and compact objective lenses, correcting chromatic aberrations. They are found in professional camera lenses, telescopes, microscopes, and photolithography instruments.

Cerium-doped lanthanum bromide (LaBr₃:Ce) is a revolutionary scintillator material. It converts gamma or X radiation into visible light with exceptional energy resolution, far superior to that of classical scintillators (NaI:Tl). It is used in the detection of radioactive materials (security, geophysics), medical imaging, and nuclear physics.

Lanthanum titanate (La₂Ti₂O₇) and derived materials exhibit interesting ferroelectric or piezoelectric properties for capacitors, sensors, and non-volatile memories.

Mischmetal (from German "Mischmetall", "mixed metal") is a natural rare earth alloy, typically containing about 50% cerium, 25-40% lanthanum, 10-15% neodymium, and small amounts of other rare earths and iron. It is an economical by-product of rare earth refining. Lanthanum contributes to its malleability and pyrophoric properties.

Lanthanum and its compounds are considered to have low to moderate toxicity, especially compared to other heavy metals. However:

The metal itself is pyrophoric in fine powder form and must be handled under an inert atmosphere.

Lanthanum is naturally present in the environment at low concentrations. Mining and refining of rare earths can generate waste (mine tailings, processing sludges) containing lanthanum and other elements, sometimes with natural radioactivity (thorium, uranium) associated with ores such as monazite. The management of this waste is a major environmental issue. Lanthanum is not considered a major pollutant due to its low mobility in soils and low toxicity.

The recycling of lanthanum is becoming crucial with the growth of its use. The main potential sources of recycling are:

Recycling is technically feasible (by hydrometallurgical processes) but is often hampered by collection, logistics, and fluctuating economic viability.

Lanthanum remains a strategic element for the energy transition:

The main challenges remain the diversification of supply outside China, improving utilization efficiency, and developing robust recycling channels.