Iridium is a heavy element synthesized almost exclusively by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during cataclysmic events such as type II supernovae or neutron star mergers. As a siderophile element (affinity for iron), it was largely drained into the iron core during Earth's planetary differentiation, explaining its extreme rarity in the Earth's crust. Its abundance in certain primitive chondritic meteorites is much higher, making it an ideal tracer of extraterrestrial matter.

The 1980 discovery by Luis and Walter Alvarez of an abnormally iridium-rich clay layer at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary (66 million years ago) worldwide revolutionized geology. This anomaly, up to 100 times the normal crustal content, could not be explained by terrestrial processes. It provided the first solid evidence for the hypothesis that the extinction of the dinosaurs (and 75% of species) was caused by the impact of a 10 km diameter asteroid. The corresponding crater was later identified at Chicxulub, Mexico.

Since this discovery, iridium anomalies have been systematically sought in geological strata as markers of major meteorite impacts. They have helped identify other extinction or biotic disruption events, such as at the Triassic-Jurassic boundary. Iridium has thus become a key element in linking Earth's history to astronomical phenomena.

Iridium has two natural stable isotopes, \(^{191}\mathrm{Ir}\) and \(^{193}\mathrm{Ir}\). The isotopic ratios of iridium, combined with those of other siderophile elements such as osmium, platinum, or ruthenium, allow distinguishing sources of extraterrestrial matter (for example, differentiating a chondritic meteorite from a differentiated meteorite) and better understanding the planetary accretion process.

Iridium takes its name from the Greek goddess of the rainbow, Iris (Ἶρις). This name was chosen by its discoverer Smithson Tennant in 1803 because of the wide variety of vivid colors exhibited by its salts in solution. Unlike osmium, discovered simultaneously and named for its odor, iridium was thus celebrated for its chromatic beauty.

Like osmium, iridium was discovered in 1803 by the English chemist Smithson Tennant. While studying the black insoluble residue obtained after dissolving native platinum in aqua regia, he managed to separate two new elements. One produced a volatile oxide with a strong odor (osmium), the other yielded salts with remarkable colors. He named the latter iridium. Its difficulty to melt and work earned it the nickname "recalcitrant metal".

The first production of relatively pure iridium metal is attributed to Tennant as early as 1804, but it was not until 1842 that the French chemist Henri Sainte-Claire Deville succeeded in obtaining significant quantities and studying its properties. Its very high melting point and extreme hardness made industrial processing very difficult until the advent of electric arc furnaces and powder metallurgy techniques in the 20th century.

Iridium is one of the rarest elements in the Earth's crust, with an estimated abundance of only 0.001 ppb (parts per billion), about 40 times rarer than gold. This rarity is explained by its siderophile nature. Like other platinum group metals, there are no primary iridium deposits. It is always recovered as a by-product of nickel and copper refining (sulfide deposits such as Norilsk) or, mainly, from platinum ore processing (Bushveld deposit in South Africa, which supplies the vast majority of the world's iridium).

Global annual production is very low, on the order of a few tons. The main producers are South Africa, Russia, Canada, and Zimbabwe. Its price is extremely high and volatile, often higher than that of gold, reflecting its rarity, the complexity of its extraction, and niche demand in high technology.

Iridium (symbol Ir, atomic number 77) is a transition metal of the 6th period, located in group 9 (formerly VIII) of the periodic table, with cobalt, rhodium, and meitnerium. It belongs to the platinum group metals (platinum, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, osmium, iridium). Its atom has 77 protons, usually 115 or 116 neutrons (for isotopes \(^{193}\mathrm{Ir}\) and \(^{191}\mathrm{Ir}\)) and 77 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁷ 6s². This configuration has seven electrons in the 5d subshell.

Iridium is a silvery-white, shiny, very dense, extremely hard, and brittle metal. It shares with osmium the title of the densest element.

Iridium has a face-centered cubic (FCC) crystal structure at room temperature.

Iridium melts at 2466 °C (2739 K) and boils at 4428 °C (4701 K). It maintains excellent mechanical and chemical stability at extreme temperatures, making it a material of choice for the most severe applications.

Iridium is the most corrosion-resistant metal. It is unattacked by all acids, including aqua regia, at room temperature. It can be slowly attacked by aqua regia at high temperature and pressure. It also resists molten alkalis. Its main chemical weakness is some surface oxidation above 600°C to form IrO₂, which is however stable and protective. This legendary inertness makes it the ideal candidate for standards and applications where purity must be preserved indefinitely.

Density: 22.56 g/cm³ - among the highest (with osmium).

Melting point: 2739 K (2466 °C) - extremely high.

Boiling point: 4701 K (4428 °C).

Crystal structure: Face-centered cubic (FCC).

Modulus of elasticity: ~528 GPa - extremely rigid.

Hardness: 6.5 on the Mohs scale.

Corrosion resistance: The highest of all metals.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iridium-191 — \(^{191}\mathrm{Ir}\) | 77 | 114 | 190.960594 u | ≈ 37.3 % | Stable | Stable isotope. Used for the production of the medical isotope \(^{192}\mathrm{Ir}\) by neutron activation. |

| Iridium-193 — \(^{193}\mathrm{Ir}\) | 77 | 116 | 192.962926 u | ≈ 62.7 % | Stable | Major stable isotope. Reference isotope for measurements. |

| Iridium-192 — \(^{192}\mathrm{Ir}\) (artificial) | 77 | 115 | 191.962605 u | Trace (radiogenic) | 73.827 days | Radioactive β⁻ and CE. Important isotope for radiotherapy (brachytherapy) and industrial gammagraphy (non-destructive testing). Produced by neutron irradiation of \(^{191}\mathrm{Ir}\). |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

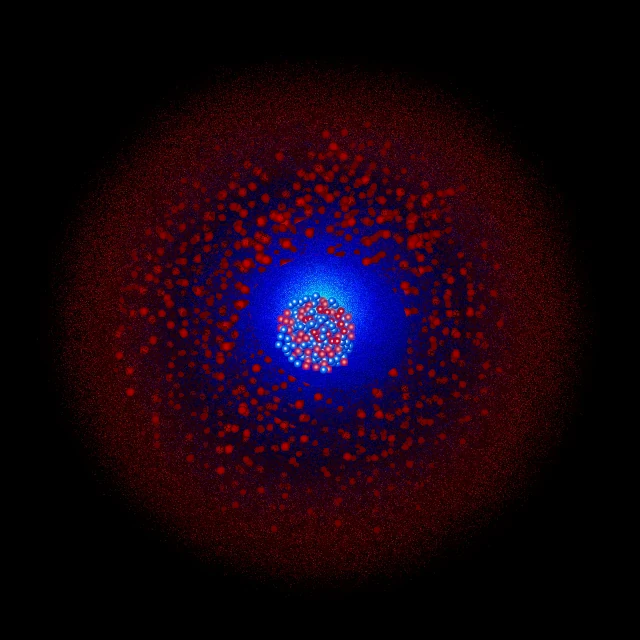

Iridium has 77 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁷ 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and seven electrons in the 5d subshell. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(15) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d⁷ 6s².

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 15 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d⁷).

P shell (n=6): 2 electrons (6s²).

Iridium has 9 valence electrons: two 6s² electrons and seven 5d⁷ electrons. Iridium exhibits a wide range of oxidation states, from -3 to +9, with the +3 and +4 states being the most common and stable.

The +3 state is very stable and is found in many complexes (e.g., \(\mathrm{IrCl_6^{3-}}\)). The +4 state is also common (e.g., \(\mathrm{IrO_2}\), \(\mathrm{IrF_6^{2-}}\)). Remarkably, iridium can reach very high oxidation states, up to +9 in the \(\mathrm{IrO_4^+}\) cation in the gas phase, which is the absolute record for any element. This richness in oxidation states, coupled with the great inertness of the base metal, makes it a fascinating element for coordination chemistry and catalysis (notably hydrosilylation catalysts and certain organometallic catalysts).

At room temperature, iridium is perfectly stable in air. It only begins to oxidize significantly above 600 °C, forming a layer of iridium dioxide (IrO₂) that is stable and adherent, offering some protection. Above 1100 °C, this oxide layer volatilizes. Unlike osmium, it does not form a volatile toxic oxide such as OsO₄.

Iridium is famous for its invulnerability to acids:

This resistance makes it ideal for laboratory crucibles intended for handling ultra-corrosive substances.

N.B.:

Iridium reacts directly with halogens at high temperature. With fluorine, it forms IrF₆ (hexafluoride, yellow solid) and IrF₄. With chlorine, it forms IrCl₃ (trichloride, brown-red solid) and IrCl₄. It also reacts with oxygen and chlorine simultaneously to form oxychlorides. It forms compounds with sulfur, selenium, tellurium, phosphorus, arsenic, silicon, and boron at high temperature.

The most important oxidation compound is iridium dioxide IrO₂.

The platinum-iridium (90/10) alloy was chosen in the late 19th century to manufacture the international prototypes of the meter and kilogram due to unique properties:

Although the meter and kilogram are now defined by fundamental constants, the old platinum-iridium standards remain historical and symbolic pieces of metrological science.

Pure iridium is the material of choice for crucibles used in the Czochralski method for growing single crystals of oxides with very high melting points, such as:

Its purity, very high melting point, and chemical inertness prevent contamination of the growing crystal.

Anodes coated with a mixture of conductive oxides (such as IrO₂ + Ta₂O₅) on a titanium substrate are called "dimensionally stable". They are electrochemically unattackable and have revolutionized the chlor-alkali industry, replacing polluting graphite anodes. They are also used for water electrolysis, water treatment, and electroplating.

The artificial radioactive isotope \(^{192}\mathrm{Ir}\) is a medium-energy gamma source (average energy ~380 keV) with a practical half-life of 74 days. It is widely used in brachytherapy, a form of radiotherapy where the radioactive source is placed inside or in the immediate vicinity of the tumor.

The same \(^{192}\mathrm{Ir}\) source is used for non-destructive testing by industrial radiography. It allows checking the integrity of welds on pipelines, pressure vessels, aeronautical structures, and cast parts. Its penetration is suitable for a wide range of steel thicknesses.

Nickel-based alloys (superalloys) or platinum reinforced with iridium are used in the most thermally and chemically stressed components:

The addition of iridium to platinum, palladium, or tungsten significantly improves the hardness, arc resistance, and wear resistance of electrical contacts used in high-power switches, aviation relays, and safety devices.

Metallic iridium is considered biologically inert and low in toxicity due to its extreme insolubility and lack of reactivity. There is virtually no risk from the bulk metal.

However:

Natural iridium is present in infinitesimal trace amounts in the environment and does not constitute a pollutant. The extraction of platinum group metals, of which it is a part, can have local environmental impacts (soil disturbance, mine waste management). Industrial activities using iridium generate little dispersive waste due to its value and status as a critical element.

The recycling of iridium is economically imperative due to its exorbitant price and rarity. It is carefully recovered from:

Recycling processes generally involve selective collection, dissolution under aggressive conditions (hot aqua regia under pressure), and purification by selective precipitation or ion exchange.

Iridium is a critical material for the European Union and the United States. Its applications in green technologies (electrolyzers for green hydrogen), high technology, and health make it a strategic element. Future challenges include:

Iridium, through its link to the greatest cosmic cataclysms and its role in the most advanced technologies, remains an element that is both a witness to the past and a key to our technological future.