Samarium is an element produced mainly by the slow neutron capture process (s-process) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. A fraction is also synthesized by the rapid neutron capture process (r-process) during cataclysmic events such as neutron star mergers or supernovae.

The abundance of samarium in stars is a valuable indicator for astronomers. The abundance ratio between samarium and other elements produced by similar processes (such as neodymium or europium) helps trace the history of nucleosynthesis in our galaxy. Measuring samarium abundances in old, metal-poor stars helps understand the relative efficiency of the s and r processes in the early universe. Furthermore, the radioactive isotope 146Sm (half-life of 68 million years) existed at the beginning of the solar system. Its past presence, detected by its decay products in meteorites, is used as a chronometer to date planetary differentiation and the formation of the cores of terrestrial planets like Earth and Mars.

The history of samarium begins with the analysis of a rare mineral, samarskite, identified in the Urals around 1847 and named after Russian Colonel Vassili Samarski (1803-1870). The Swiss chemist Jean Charles Galissard de Marignac (1817-1894) was the first to observe unknown spectral lines in this mineral in 1853, suggesting the presence of a new element. However, it was the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1838-1912) who, in 1879, succeeded in isolating an oxide of a new element from samarskite. He confirmed his discovery by spectroscopy and named this element samarium after the original mineral. This was the first identification of a rare earth element from this mineral, paving the way for the discovery of other lanthanides.

N.B.:

Samarium does not occur in its native state. It is mainly extracted from ores such as monazite and bastnäsite, which contain a mixture of rare earths. Its abundance in the Earth's crust is about 7 ppm, which is higher than that of elements like tin. The separation of samarium from other lanthanides, a complex process due to their very similar chemical properties, is achieved by modern techniques such as ion exchange or solvent extraction.

Samarium (symbol Sm, atomic number 62) is an element of the lanthanide series, belonging to the rare earth group. Its atom has 62 protons, usually 90 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{152}\mathrm{Sm}\)) and 62 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁶ 6s².

At room temperature, samarium is a silvery, relatively hard and brittle solid metal. It is a moderately dense element (density ≈ 7.52 g/cm³) and exhibits slight magnetism at room temperature.

Melting point (liquid state) of samarium: 1,345 K (1,072 °C).

Boiling point (gaseous state) of samarium: 2,067 K (1,794 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samarium-152 — \(\,^{152}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 90 | 151.919732 u | ≈ 26.75 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope. |

| Samarium-154 — \(\,^{154}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 92 | 153.922209 u | ≈ 22.75 % | Stable | Second stable isotope. |

| Samarium-147 — \(\,^{147}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 85 | 146.914898 u | ≈ 14.99 % | 1.06 × 10¹¹ years | Radioactive, α-emitter. Fundamental for geological dating (Sm-Nd). |

| Samarium-149 — \(\,^{149}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 87 | 148.917185 u | ≈ 13.82 % | Stable | Stable isotope. It is a powerful neutron poison. |

| Samarium-150 — \(\,^{150}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 88 | 149.917276 u | ≈ 7.38 % | Stable | Stable isotope. |

| Samarium-144 — \(\,^{144}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 82 | 143.912006 u | ≈ 3.07 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope. |

| Samarium-153 — \(\,^{153}\mathrm{Sm}\,\) | 62 | 91 | 152.922097 u | Synthetic | 46.3 hours | β⁻-emitter. Used in nuclear medicine for the treatment of bone pain. |

N.B.:

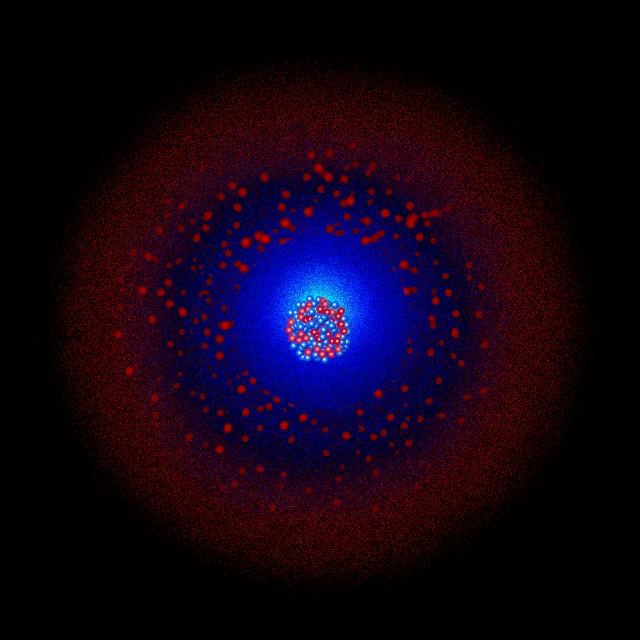

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Samarium has 62 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁶ 4f⁶ 6s², or simplified: [Xe] 4f⁶ 6s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(24) O(8) P(2).

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 24 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f⁶). The 4f subshell, partially filled with 6 electrons, is responsible for the unique magnetic and optical properties of samarium.

O shell (n=5): 8 electrons (5s² 5p⁶).

P shell (n=6): 2 electrons (6s²).

The valence electrons of samarium are mainly the 2 electrons 6s², but the 6 electrons 4f also actively participate in chemical bonding. This configuration leads to several possible oxidation states.

The most common and stable oxidation state is +3 (Sm³⁺), where the atom loses its two 6s² electrons and one 4f electron, reaching a particularly stable [Xe] 4f⁵ configuration (half-filled f subshell).

The oxidation state +2 (Sm²⁺) is also known and relatively stable for a lanthanide, where the atom loses only its two 6s² electrons to give [Xe] 4f⁶. Sm²⁺ is a powerful reducing agent.

This duality (+2/+3) gives samarium a rich chemistry, used in reduction applications in organic synthesis.

Samarium is a relatively reactive metal. It tarnishes slowly in air, forming an oxide (Sm₂O₃) on its surface. In powdered form, it can spontaneously ignite. It reacts with water to release hydrogen, although more slowly than alkaline earth metals. It dissolves easily in dilute acids. Samarium reacts with most non-metals (halogens, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur) at moderate temperatures. Its aqueous chemistry is dominated by the Sm³⁺ ion, which forms stable complexes and exhibits a characteristic pale yellow color.