Barium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. Barium is one of the signature elements of the s-process, with significantly increased abundances in these evolved stars. The r-process (rapid neutron capture) also contributes to barium production during cataclysmic events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers.

The cosmic abundance of barium is about 4×10⁻¹⁰ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it a relatively rare element in the universe but significantly more abundant than elements like antimony or mercury. This moderate abundance is explained by barium's favorable position on the nuclear stability curve and the efficiency of the s-process in producing medium-mass elements.

The spectral lines of neutral barium (Ba I) and ionized barium (Ba II) are easily observable in stellar spectra, particularly the Ba II lines in the near ultraviolet and visible. Barium is an important indicator of s-process enrichment in stars. "Barium stars" represent a particular class of cool giant stars abnormally enriched in barium and other s-process elements.

The origin of these barium stars was long mysterious. It is now understood that they are generally binary systems where the companion is a white dwarf that was previously an AGB star enriched in s-process elements. Mass transfer from the former AGB star to the currently visible star enriched the latter in barium. The study of barium stars helps constrain models of s-process nucleosynthesis and the evolution of binary systems.

Barium takes its name from the Greek barys, meaning "heavy," referring to the high density of its ores. Barite (barium sulfate, BaSO₄), the main barium ore, has been known since the early 17th century. In 1602, Vincenzo Casciarolo, a Bologna shoemaker and alchemist, discovered that Bolognian barite, when heated with charcoal, produced a phosphorescent substance that glowed in the dark after exposure to light. This "Bologna stone" intrigued European scholars for over a century.

In 1774, Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742-1786), a Swedish chemist, distinguished a new earthy oxide in pyrolusite and demonstrated that barite contained an unknown element. That same year, Swedish mineralogist Johan Gottlieb Gahn also isolated this oxide. However, isolating metallic barium proved extremely difficult due to its extreme reactivity.

It was not until 1808 that Sir Humphry Davy (1778-1829), a British chemist, succeeded in isolating metallic barium by electrolysis of moistened molten barium hydroxide, using a powerful voltaic pile. In that remarkable year, Davy also isolated calcium, strontium, and magnesium using similar methods, revolutionizing alkaline earth metal chemistry.

Barium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 425 ppm, making it the 14th most abundant element on Earth, more abundant than carbon or sulfur. The main barium ores are barite or baryte (BaSO₄), containing about 58.8% barium, and witherite (BaCO₃), containing about 69.6% barium, although the latter is much rarer.

Global barite production is about 8 to 9 million tons per year. China dominates production with about 35-40% of the global total, followed by India, Morocco, Kazakhstan, Turkey, and the United States. Unlike other strategic metals, barium production is relatively geographically diversified.

Metallic barium is produced only in modest quantities, about 10,000 tons per year, mainly by aluminothermic reduction of barium oxide. Most applications use barium compounds directly, particularly barium sulfate, without requiring metal isolation. Barium recycling is negligible, accounting for less than 1% of supply, as barium is generally used in dispersive applications where recovery is economically unviable.

Barium (symbol Ba, atomic number 56) is an alkaline earth metal in group 2 of the periodic table, along with beryllium, magnesium, calcium, strontium, and radium. Its atom has 56 protons, usually 82 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{138}\mathrm{Ba}\)) and 56 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 6s².

Barium is a soft, silvery-white metal that tarnishes rapidly in air, forming a layer of oxide and nitride. It has a density of 3.51 g/cm³, relatively low for a "heavy" metal. Barium crystallizes in a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure at room temperature. It is a very soft metal that can be cut with a knife and has moderate ductility.

Barium melts at 727 °C (1000 K) and boils at 1845 °C (2118 K). It is an excellent conductor of electricity and heat, typical properties of metals. Its electrical conductivity is about 17 times lower than that of copper but remains high. Barium has the second lowest ionization potential among stable elements (after cesium), explaining its extreme chemical reactivity.

Barium is extremely reactive and must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation. It reacts vigorously with water, even at room temperature, producing barium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Barium spontaneously ignites in humid air and burns with a characteristic pale green flame.

Melting point of barium: 1000 K (727 °C).

Boiling point of barium: 2118 K (1845 °C).

Barium has extreme chemical reactivity, spontaneously igniting in humid air.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barium-130 — \(\,^{130}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 74 | 129.906321 u | ≈ 0.106 % | Stable | Rare stable isotope of barium, representing about 0.1% of the natural total. |

| Barium-132 — \(\,^{132}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 76 | 131.905061 u | ≈ 0.101 % | Stable | Rare stable isotope, slightly more abundant than Ba-130. |

| Barium-134 — \(\,^{134}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 78 | 133.904508 u | ≈ 2.417 % | Stable | Minor stable isotope of barium, representing about 2.4% of the total. |

| Barium-135 — \(\,^{135}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 79 | 134.905689 u | ≈ 6.592 % | Stable | Stable isotope representing about 6.6% of natural barium. |

| Barium-136 — \(\,^{136}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 80 | 135.904576 u | ≈ 7.854 % | Stable | Stable isotope representing about 7.9% of natural barium. |

| Barium-137 — \(\,^{137}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 81 | 136.905827 u | ≈ 11.232 % | Stable | Stable isotope representing about 11.2% of natural barium. |

| Barium-138 — \(\,^{138}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 82 | 137.905247 u | ≈ 71.698 % | Stable | Ultra-dominant isotope of barium, representing over 71% of the natural total. |

| Barium-140 — \(\,^{140}\mathrm{Ba}\,\) | 56 | 84 | 139.910605 u | Synthetic | ≈ 12.75 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Important fission product, used in nuclear medicine and as a tracer. |

N.B.:

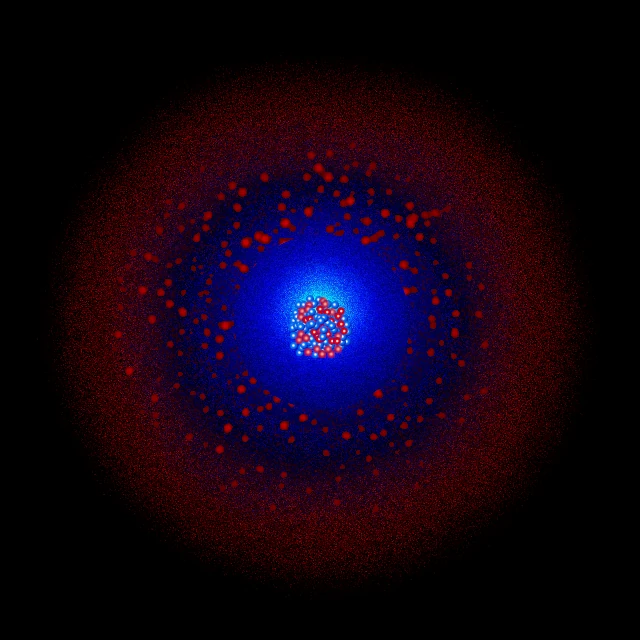

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Barium has 56 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s², or simplified: [Xe] 6s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(18) P(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable and complete structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 18 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴. The complete 4f subshell is particularly stable.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These two electrons are the valence electrons of barium.

Barium has 2 valence electrons: two 6s² electrons. The almost exclusive oxidation state of barium is +2, where barium loses its two 6s² electrons, forming the Ba²⁺ ion isoelectronic with xenon. This stable noble gas electronic configuration explains why the +2 state completely dominates barium chemistry.

The +2 state appears in virtually all barium compounds: barium oxide (BaO), barium hydroxide (Ba(OH)₂), barium sulfate (BaSO₄), barium carbonate (BaCO₃), barium chloride (BaCl₂), and many others. Metallic barium corresponds to the oxidation state 0, but it is extremely rare due to barium's strong tendency to oxidize.

Barium compounds with unusual oxidation states (+1) have been synthesized under extreme laboratory conditions, but these compounds are extremely unstable and have no practical relevance. The chemistry of barium is therefore essentially the chemistry of the Ba²⁺ ion.

Barium is one of the most reactive metals. In air, it tarnishes immediately, forming a layer of barium oxide (BaO) and barium nitride (Ba₃N₂): 2Ba + O₂ → 2BaO and 3Ba + N₂ → Ba₃N₂. This protective layer partially slows further oxidation but does not completely stop the reaction. At high temperatures, barium burns vigorously in air with a characteristic pale green flame.

Barium reacts vigorously with water at room temperature, producing barium hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas: Ba + 2H₂O → Ba(OH)₂ + H₂↑. This reaction is exothermic and energetic enough to ignite the released hydrogen. The barium hydroxide formed is a strong soluble base, creating a highly alkaline solution (pH > 13).

Barium reacts with halogens to form halides: Ba + Cl₂ → BaCl₂. It also reacts with sulfur to form barium sulfide (BaS), and with hydrogen at high temperatures to form barium hydride (BaH₂). Barium dissolves in acids, even diluted ones, with the release of hydrogen: Ba + 2HCl → BaCl₂ + H₂↑.

Barium sulfate (BaSO₄) has a remarkable property: it is extremely insoluble in water (only 0.00022 g/100 mL at 20 °C), making it non-toxic despite the high toxicity of other soluble barium compounds. This exceptional insolubility is the basis for the medical use of barium sulfate as a radiological contrast agent.

The dominant application of barium, accounting for about 75-80% of global barite consumption, is its use in drilling fluids for oil and gas extraction. Ground barite (natural barium sulfate, BaSO₄) is added to drilling muds to increase their density, allowing control of formation pressures in deep wells.

Drilling fluids must balance the pressure of geological formations to prevent uncontrolled eruptions (blowouts) while maintaining well stability. Barite is ideal for this application because it combines high density (4.5 g/cm³), exceptional chemical inertia, relative non-toxicity, and moderate cost. A typical offshore oil well can consume 1000 to 3000 tons of barite.

The demand for barite for drilling fluids fluctuates significantly with oil prices and global drilling activity. Strict technical specifications require high-purity barite (>95% BaSO₄) with controlled particle size distribution. The oil industry is the main economic driver of the global barium market.

Ultra-pure pharmaceutical barium sulfate (BaSO₄) has been the standard radiological contrast agent for gastrointestinal imaging for over a century. Its exceptional X-ray absorption capacity, combined with its complete insolubility in water and body fluids, makes it an ideal and safe contrast agent.

Patients ingest or receive a barium sulfate suspension rectally before radiographic or computed tomography (CT) scans of the digestive system. Barium opacifies gastrointestinal structures, allowing the detection of tumors, ulcers, obstructions, perforations, and other abnormalities. A typical gastrointestinal X-ray uses 200-500 grams of barium sulfate.

Medical barium sulfate must meet extremely strict purity standards (>99% BaSO₄) to ensure the absence of toxic soluble barium compounds. Despite the emergence of alternatives such as iodinated contrast agents for some applications, barium sulfate remains essential for many digestive examinations, accounting for about 2-3% of global barium consumption.

Soluble barium compounds (chloride, nitrate, hydroxide, carbonate) are highly toxic. Ingestion of soluble barium salts causes severe hypokalemia (low blood potassium), leading to serious cardiac disorders, muscle paralysis, seizures, and potentially death. The lethal dose of barium chloride for an adult is about 1-2 grams.

The toxicity mechanism involves the blocking of potassium channels in muscle and nerve cells by the Ba²⁺ ion, severely disrupting neuromuscular and cardiac function. Symptoms of acute poisoning appear within a few hours: vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, progressive muscle weakness, tremors, cardiac arrhythmias, and respiratory difficulty.

In contrast, barium sulfate (BaSO₄) is considered non-toxic due to its extreme insolubility. It passes through the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed and is completely eliminated in the feces, allowing its safe medical use. However, even barium sulfate can become dangerous if inhaled as fine dust, causing pneumoconiosis (baritosis) in chronically exposed workers.

Environmental exposure to barium mainly comes from industrial discharges, particularly from extractive and chemical industries. Barium accumulates moderately in soils and can contaminate groundwater in mining areas. Drinking water standards generally set the limit at 1-2 mg/L to protect against long-term cardiovascular effects.