Thulium is synthesized in stars almost exclusively by the s-process (slow neutron capture) occurring in low- to medium-mass AGB stars (asymptotic giant branch). Unlike lighter lanthanides such as europium, thulium shows a very low contribution from the r-process (rapid neutron capture), estimated at less than 10% of its solar abundance. This is due to its position in the heavy rare earth region where the s-process becomes dominant. Thulium is therefore almost a pure tracer of the s-process, in contrast to europium.

The cosmic abundance of thulium is about 2.0×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it one of the least abundant lanthanides, comparable to lutetium and about 5 times less abundant than holmium. Its extreme rarity is explained by several factors: its odd atomic number (Tm, Z = 69) according to the Oddo-Harkins rule, its position at the end of the neutron capture chain, and the fact that it is mainly produced by the s-process, which is less efficient for heavy nuclei than the r-process for some of its neighbors.

Due to its dominant production by the s-process, thulium is used in astrophysics as a specific indicator of this process. The thulium/europium (Tm/Eu) ratio in stars is particularly revealing: a high ratio indicates a strong contribution from the s-process, while a low ratio suggests a dominance of the r-process. In stars enriched in s-process elements (such as barium stars), thulium is often overabundant compared to r-process elements. These measurements help quantify the relative importance of AGB stars in galactic chemical enrichment.

Detecting thulium in stellar atmospheres is extremely difficult due to the rarity of the element and the weakness of its spectral lines. Only a few lines of the Tm II ion are potentially detectable, requiring very high resolution and high signal-to-noise ratio spectra. Despite these difficulties, thulium has been detected in certain peculiar stars rich in s-process elements. These detections provide valuable constraints on nucleosynthesis models in AGB stars and on the efficiency of the production of the heaviest rare earths.

Thulium takes its name from Thule, a term used in antiquity and the Middle Ages to designate the northernmost region of the known world, often associated with Scandinavia or Iceland. The discoverer, Per Teodor Cleve, chose this name to evoke the distant north, continuing the tradition of naming rare earths after geographical places (Ytterby, Stockholm). Thule represented the ultimate limit of the known world, appropriate for a rare and difficult-to-obtain element.

Thulium was discovered in 1879 by the Swedish chemist Per Teodor Cleve (1840-1905), who also discovered holmium the same year. While working on erbia (erbium oxide), Cleve succeeded in separating two new oxides by repeated fractional crystallizations: a brown one he named holmia (holmium oxide) and a green one he named thulia (thulium oxide). He demonstrated that thulia was the oxide of a new element, which he named thulium. Cleve was an expert in rare earths and used both chemical and spectroscopic methods to characterize his discoveries.

Isolating thulium in pure form was a major challenge due to its great chemical similarity with other heavy rare earths, particularly erbium and ytterbium. It was not until 1911 that the American chemist Charles James succeeded in obtaining relatively pure thulium through complex fractional crystallizations of bromates. The metal itself was first produced the same year by reducing the oxide with lanthanum. However, it was only with the development of ion exchange techniques in the 1950s that high-purity thulium became available.

Thulium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.5 ppm (parts per million), making it the second rarest lanthanide after promethium (which is radioactive and practically absent from the crust), and one of the rarest elements overall. The main ores containing thulium are bastnäsite ((Ce,La,Nd,Tm)CO₃F) and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Tm,Th)PO₄), where it typically represents 0.01 to 0.05% of the total rare earth content, and xenotime (YPO₄) where it can be slightly more concentrated.

Global production of thulium oxide (Tm₂O₃) is about 50 to 100 kilograms per year, making it one of the least produced rare earths in terms of mass. Due to this extreme rarity and its highly specialized, high value-added applications, thulium is the most expensive rare earth, with typical prices of $3,000 to $10,000 per kilogram of oxide (or more depending on purity). China dominates production, but even there, thulium is produced in minuscule quantities compared to other rare earths.

Thulium metal is produced mainly by metallothermic reduction of thulium fluoride (TmF₃) with metallic calcium in an inert argon atmosphere. Global annual production of thulium metal is only a few kilograms. Recycling of thulium is virtually non-existent due to the tiny amounts used and the extreme difficulty of recovering it from complex finished products.

Thulium (symbol Tm, atomic number 69) is the thirteenth element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the f-block rare earths of the periodic table. Its atom has 69 protons, 100 neutrons (for the only stable isotope \(\,^{169}\mathrm{Tm}\)) and 69 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹³ 6s². This configuration has thirteen electrons in the 4f subshell, one less than a full subshell.

Thulium is a silvery, bright, malleable metal, soft enough to be cut with a knife. It has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature. Thulium is paramagnetic at room temperature and exhibits complex magnetic transitions at low temperatures. It becomes antiferromagnetic below 58 K (-215 °C), then ferromagnetic below 32 K (-241 °C). Although these temperatures are very low, these properties are studied for fundamental research in magnetism.

Thulium melts at 1545 °C (1818 K) and boils at 1950 °C (2223 K). It has high melting and boiling points, typical of lanthanides, but its boiling point is relatively low compared to its neighbors. Thulium undergoes an allotropic transformation at 1500 °C where its crystal structure changes from hexagonal close-packed (HCP) to body-centered cubic (BCC). Its electrical conductivity is poor, about 25 times lower than that of copper.

Thulium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, but oxidizes slowly to form a greenish-white Tm₂O₃ oxide. It oxidizes more rapidly when heated and burns to form the oxide: 4Tm + 3O₂ → 2Tm₂O₃. Thulium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form thulium(III) hydroxide Tm(OH)₃ and release hydrogen. It dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids. The metal must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert atmosphere to prevent gradual oxidation.

Melting point of thulium: 1818 K (1545 °C).

Boiling point of thulium: 2223 K (1950 °C).

Néel temperature (antiferromagnetic transition): 58 K (-215 °C).

Curie temperature (ferromagnetic transition): 32 K (-241 °C).

Crystal structure at room temperature: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thulium-169 — \(\,^{169}\mathrm{Tm}\,\) | 69 | 100 | 168.934213 u | ≈ 100 % | Stable | Only natural stable isotope of thulium. Used as a target to produce the radioactive isotope Tm-170. |

| Thulium-170 — \(\,^{170}\mathrm{Tm}\,\) | 69 | 101 | 169.935801 u | Synthetic | ≈ 128.6 days | Radioactive (β⁻, CE). Weak beta and gamma emitter, used as a portable X-ray source and in brachytherapy. |

| Thulium-171 — \(\,^{171}\mathrm{Tm}\,\) | 69 | 102 | 170.936429 u | Synthetic | ≈ 1.92 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Used in research and as a tracer. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

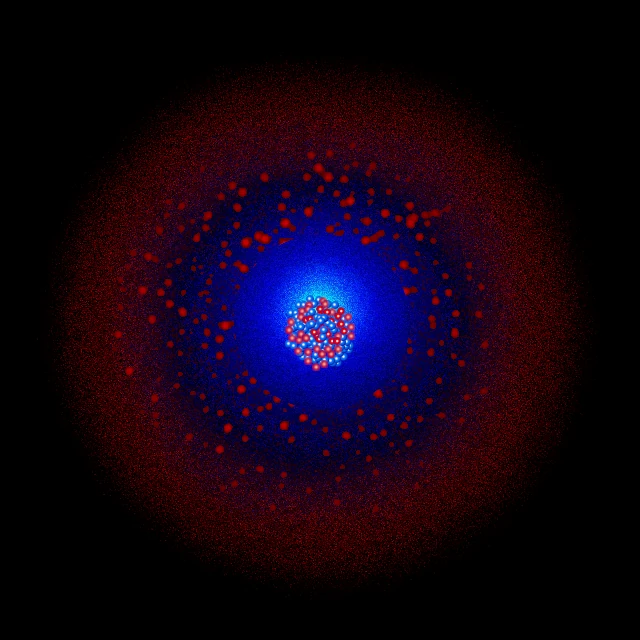

Thulium has 69 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹³ 6s² has thirteen electrons in the 4f subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(31) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹³ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 31 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹³ 5d⁰. The thirteen 4f electrons (one less than a full subshell) give thulium its optical and magnetic properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of thulium.

Thulium effectively has 15 valence electrons: thirteen 4f¹³ electrons and two 6s² electrons. Thulium exhibits almost exclusively the +3 oxidation state in its stable compounds. In this state, thulium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Tm³⁺ ion with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹². This ion has twelve electrons in the 4f subshell and exhibits interesting luminescent properties.

Unlike most other lanthanides, thulium can also form relatively stable compounds in the +2 oxidation state, although these are less common than +3 compounds. The Tm²⁺ ion has the configuration [Xe] 4f¹³, which corresponds to an almost full 4f subshell (missing one electron), giving it some stability. Thulium(II) compounds, such as TmI₂ (thulium diiodide) or TmCl₂, are however strongly reducing and sensitive to oxidation. No thulium(IV) compounds are known under normal conditions.

The chemistry of thulium is therefore mainly that of the +3 state. The Tm³⁺ ion has an ionic radius of 103.0 pm (for coordination number 8) and forms complexes that are generally colorless or weakly colored in aqueous solution. Its luminescent properties are exploited in certain lasers and optical materials. Thulium salts are paramagnetic.

Thulium metal is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, forming a thin protective layer of Tm₂O₃ oxide. At high temperature (above 150 °C), it oxidizes rapidly and burns to form the oxide: 4Tm + 3O₂ → 2Tm₂O₃. Thulium(III) oxide is a pale greenish-white solid with a cubic C-type rare earth structure. In fine powder form, thulium is pyrophoric and can spontaneously ignite in air.

Thulium reacts slowly with cold water and more rapidly with hot water to form thulium(III) hydroxide Tm(OH)₃ and release hydrogen gas: 2Tm + 6H₂O → 2Tm(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. The hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous white solid with low solubility. As with other lanthanides, the reaction is not violent but is observable over time.

Thulium reacts with all halogens to form the corresponding trihalides: 2Tm + 3F₂ → 2TmF₃ (white fluoride); 2Tm + 3Cl₂ → 2TmCl₃ (pale yellow chloride). Thulium dissolves easily in dilute mineral acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) with the release of hydrogen and the formation of the corresponding Tm³⁺ salts: 2Tm + 6HCl → 2TmCl₃ + 3H₂↑.

Thulium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperature (300-400 °C) to form TmH₂ hydride, then TmH₃ at higher temperature. With sulfur, it forms Tm₂S₃ sulfide. It reacts with nitrogen at high temperature (>1000 °C) to form TmN nitride, and with carbon to form TmC₂ carbide. Thulium also forms coordination complexes with organic ligands, although this chemistry is less developed than for some other lanthanides.

The Tm³⁺ ion exhibits interesting luminescent properties in the near infrared. When excited, it can emit at several wavelengths, particularly around 1.8 µm and 2.0 µm. These infrared emissions are exploited in thulium-doped fiber lasers and in certain optical materials. The blue luminescence of thulium, although less intense than that of other lanthanides, is also sometimes used in specialized applications.

The most important application of thulium is its use as an active ion in solid-state lasers, particularly the Tm:YAG laser. In this laser, Tm³⁺ ions are incorporated into a YAG crystal (yttrium aluminum garnet, Y₃Al₅O₁₂). The Tm:YAG laser emits in the mid-infrared at a wavelength of about 2.0 micrometers (2000 nm), very close to that of the Ho:YAG laser (2.1 µm), giving it similar properties but with some advantageous differences.

The Tm:YAG laser is used in several areas of minimally invasive surgery:

The Tm:YAG laser is particularly appreciated for its energy efficiency (can be pumped by laser diodes) and its ability to operate in continuous or high repetition rate mode, allowing for rapid procedures.

Thulium-doped fiber lasers emitting around 1.9-2.0 µm have seen rapid development. They are compact, robust, efficient, and can deliver high powers. Applications:

Thulium is also used in other crystalline matrices such as YLF (yttrium lithium fluoride, LiYF₄) for specific applications requiring certain optical properties (e.g., emission at slightly different wavelengths).

The radioactive isotope thulium-170 (¹⁷⁰Tm) is used as a portable X-ray source. Tm-170 decays by beta emission (β⁻) to ytterbium-170 (¹⁷⁰Yb), emitting low-energy electrons (max 968 keV). When these electrons strike an appropriate target (usually integrated into the source), they produce bremsstrahlung radiation, which constitutes a low-energy X-ray beam (mainly below 100 keV). This source requires no electrical power, X-ray tube, or cooling system.

Tm-170 is produced by neutron irradiation of the stable isotope thulium-169 in a nuclear reactor: ¹⁶⁹Tm(n,γ)¹⁷⁰Tm. After irradiation, the source is encapsulated in a sealed housing to prevent contamination and attenuate radiation. A typical source contains a few hundred megabecquerels (MBq) to a few gigabecquerels (GBq) of Tm-170.

Brachytherapy is a form of radiotherapy where radioactive sources are placed inside or in the immediate vicinity of the tumor to be treated. This allows a high dose of radiation to be delivered to the tumor while sparing the surrounding healthy tissues.

Tm-170 has been studied and used for permanent brachytherapy of prostate cancer. Tiny seeds containing Tm-170 are implanted directly into the prostate under ultrasound guidance. The low-energy beta emission of Tm-170 (max 968 keV, average 96 keV) delivers a high dose over a very short distance (a few millimeters), which is ideal for treating the prostate while minimizing irradiation of nearby organs (rectum, bladder). The half-life of 128.6 days means that the source loses most of its activity within about a year, after which the seeds remain inactive in the body.

Tm-170 is also being studied for the treatment of other cancers (liver, breast) and for intravascular radiotherapy (prevention of restenosis after angioplasty). Research continues to develop new forms of sources (microspheres, wires) and to combine Tm-170 with vectors that specifically target tumor cells.

Thulium(III) compounds are used as activators in certain phosphors emitting in the blue (around 450 nm) or infrared. These phosphors can be used in special displays, radiation detectors (scintillators), and security markers. The blue luminescence of thulium is sometimes combined with that of other lanthanides to produce white light in specialized LEDs.

Thulium can be used as a minor additive in certain permanent magnets based on samarium-cobalt (SmCo) or neodymium-iron-boron (Nd-Fe-B) to slightly improve certain properties such as coercivity or thermal stability. However, its use is very limited due to its prohibitive cost and the availability of cheaper alternatives (dysprosium, terbium).

Due to its complex magnetic properties at low temperatures and its Tm³⁺ ion with interesting energy levels, thulium is used as a model material in research on solid-state physics, magnetism, and spectroscopy. Thulium-doped crystals are used to study interactions between magnetic ions and cooperative phenomena.

Thulium and its compounds have low chemical toxicity, comparable to other lanthanides. As with other rare earths, acute toxicity is moderate, with typical LD50 (median lethal dose) values above 500 mg/kg for salts in rodents. No carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic effects have been demonstrated. Thulium has no known biological role.

In case of exposure, thulium behaves like other lanthanides: it accumulates mainly in the liver and bones, with very slow elimination (biological half-life of several years for the bone fraction). General population exposure is extremely low, practically nil, due to the extreme rarity of the element and its very specialized applications.

For the Tm-170 isotope used in X-ray sources and brachytherapy, strict radiation protection precautions are necessary. The main risk is external exposure to X-rays and beta radiation, and potentially internal contamination in case of source rupture. Sources are therefore doubly encapsulated in resistant materials. The half-life of 128.6 days is an advantage for safety (the source quickly loses its activity if lost) but requires regular renewal for industrial applications.

The environmental impacts specifically related to thulium are negligible due to the tiny amounts produced. The general impacts of rare earth extraction apply, but thulium's contribution to these impacts is minuscule. Extracting one kilogram of thulium theoretically requires the processing of several thousand tons of ore, but in practice, thulium is recovered as a by-product of the extraction of more abundant rare earths.

Recycling of thulium is practically non-existent and probably not economical due to the extremely small amounts used. Used Tm-170 sources are treated as low-level radioactive waste. Lasers and other equipment containing thulium are generally disposed of without recovery of the metal. If demand were to increase significantly in the future, recycling could become feasible, but the techniques would be similar to those for other rare earths and would be very costly.

Occupational exposure is limited to the few workers involved in the production of thulium compounds, the manufacture of radioactive sources or lasers, and the medical or industrial use of these devices. Standard precautions for metal dusts (for stable thulium) and radiation protection (for Tm-170) apply. Due to the rarity of the element, the number of exposed people is very low.