Scandium has a particularly remarkable history because its existence was predicted before its discovery. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev (1834-1907), while developing his periodic table of elements, predicted the existence of an unknown element he named ekaboron (literally "above boron"), accurately describing its supposed properties: atomic mass around 44, density around 3.5 g/cm³, formation of an oxide Eb₂O₃. Ten years later, in 1879, the Swedish chemist Lars Fredrik Nilson (1840-1899) discovered a new element in euxenite and gadolinite ores extracted from Scandinavian mines. He named this element scandium (from Latin Scandia = Scandinavia) in honor of his region of origin. Shortly afterward, Per Teodor Cleve (1840-1905) demonstrated that Nilson's scandium exactly matched Mendeleev's predicted ekaboron, spectacularly validating the predictive power of the periodic table. This confirmation, along with those of gallium (1875) and germanium (1886), definitively established the validity of Mendeleev's periodic classification.

Scandium (symbol Sc, atomic number 21) is the first transition metal in the periodic table, belonging to group 3. Its atom has 21 protons, 21 electrons, and usually 24 neutrons in its only stable isotope (\(\,^{45}\mathrm{Sc}\)).

At room temperature, scandium is a solid, silvery-white metal with a slight yellowish tint, relatively soft and light. Density ≈ 2.985 g/cm³. Melting point of scandium: 1,814 K (1,541 °C). Boiling point: 3,109 K (2,836 °C). Scandium tarnishes in air, forming a yellowish oxide layer. It reacts slowly with hot water and dissolves easily in dilute acids, releasing dihydrogen. Scandium has unusual properties: it chemically resembles the rare earths (lanthanides) rather than aluminum, despite being in the same group. Its electronic configuration [Ar] 3d¹ 4s² gives it transition properties between alkaline earth metals and true transition metals.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scandium-45 — \(\,^{45}\mathrm{Sc}\,\) | 21 | 24 | 44.955908 u | 100 % | Stable | Only natural isotope of scandium; mononuclidic. |

| Scandium-46 — \(\,^{46}\mathrm{Sc}\) | 21 | 25 | 45.955168 u | Not natural | 83.79 days | Radioactive β\(^-\) decaying into titanium-46. Used as a radioactive tracer in medicine and industry. |

| Scandium-47 — \(\,^{47}\mathrm{Sc}\) | 21 | 26 | 46.952407 u | Not natural | 3.349 days | Radioactive β\(^-\) decaying into titanium-47. Promising in targeted cancer therapy. |

| Scandium-44 — \(\,^{44}\mathrm{Sc}\) | 21 | 23 | 43.959403 u | Not natural | 3.97 hours | Radioactive β\(^+\) and electron capture decaying into calcium-44. Used in PET imaging (positron emission tomography). |

| Other isotopes — \(\,^{36}\mathrm{Sc}\) to \(\,^{60}\mathrm{Sc}\) | 21 | 15 — 39 | — (variable) | Not natural | Milliseconds to hours | Very unstable isotopes produced artificially; research in nuclear physics. |

N.B. :

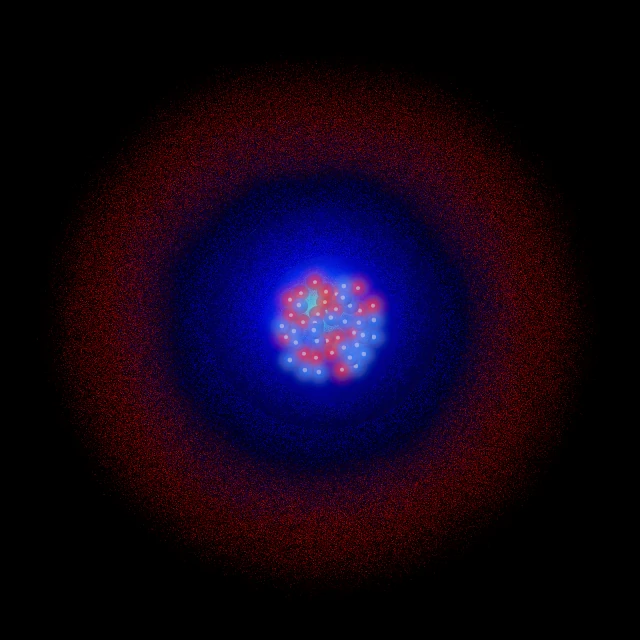

Electron shells: How electrons organize around the nucleus.

Scandium has 21 electrons distributed across four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹ 4s², or simplified as: [Ar] 3d¹ 4s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(9) N(2).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and highly stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 9 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹. The 3s and 3p orbitals are complete, while the 3d orbital contains only one electron out of 10 possible.

N Shell (n=4): contains 2 electrons in the 4s subshell. These electrons are the first to be involved in chemical bonding.

The 3 electrons in the outer shells (3d¹ 4s²) are the valence electrons of scandium. This configuration explains its chemical properties:

By losing the 2 electrons in the 4s subshell, scandium forms the Sc²⁺ ion (oxidation state +2), a relatively rare and unstable state.

By losing the 2 electrons in the 4s subshell and the electron in the 3d orbital, it forms the Sc³⁺ ion (oxidation state +3), the most stable and practically the only oxidation state observed in its compounds.

The unique electronic configuration of scandium, with its single electron in the 3d orbital, places it as the first element in the transition metal series. This structure gives it specific properties: unlike other transition metals that often exhibit multiple oxidation states, scandium is almost exclusively trivalent (Sc³⁺). The Sc³⁺ ion, having lost its 3d electron, adopts an electronic configuration identical to that of argon [Ar], which explains the great stability of this oxidation state. This particularity makes scandium an atypical transition metal, generally forming colorless compounds due to the absence of d electrons in the Sc³⁺ ion.

Scandium mainly forms compounds in the +III oxidation state, typical behavior of rare earths. It oxidizes slowly in air, forming a protective yellowish scandium oxide (Sc₂O₃) layer. At high temperatures, scandium burns easily, producing white scandium oxide. It reacts with acids (hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric) releasing dihydrogen and forming scandium (III) salts. Scandium also reacts with halogens to form halides (ScCl₃, ScF₃). Scandium compounds include scandium oxide (Sc₂O₃), scandium chloride (ScCl₃), scandium sulfate (Sc₂(SO₄)₃), and various organometallic complexes. Chemically, scandium behaves more like yttrium and rare earths than aluminum, despite its position in group 3.

The most important application of scandium lies in aluminum-scandium (Al-Sc) alloys, discovered in the 1970s in the Soviet Union. Adding only 0.1 to 0.5% scandium to aluminum produces spectacular effects: a 50% increase in mechanical strength, significant improvement in corrosion resistance, better weldability, and retention of mechanical properties at high temperatures. These alloys have an exceptional strength-to-weight ratio, even superior to titanium for certain applications. Scandium forms nanometric Al₃Sc precipitates in the aluminum matrix that block dislocation movement and refine the crystalline structure. These extraordinary properties make Al-Sc alloys the ideal material for aerospace (aircraft structures, rocket components such as SpaceX's Falcon 9), professional sports equipment, and applications where weight must be minimal while maintaining maximum strength. The main obstacle to their widespread use remains the high cost of scandium.

Paradoxically, scandium is not particularly rare in terms of geochemical abundance: it is about as abundant as lead in the Earth's crust (about 22 parts per million). However, scandium is extremely dispersed and almost never forms economically exploitable concentrated deposits. It is found in traces in more than 800 different minerals, mainly in rare earth, uranium, tungsten, and aluminum ores. The minerals richest in scandium are thortveitite ((Sc,Y)₂Si₂O₇) and kolbeckite (ScPO₄·2H₂O), but they are extremely rare. Scandium is currently extracted mainly as a by-product of the processing of other metal ores, particularly during uranium refining, bauxite residue (aluminum) treatment, and rare earth processing. China, Russia, and Ukraine are the main producers. Global annual production of scandium is only about 15 to 20 tons of scandium oxide, making it extremely expensive (about $3,000 to $5,000 per kilogram).

Scandium is produced in massive stars during advanced stages of nucleosynthesis, mainly by neutron capture. Supernovae disperse scandium into the interstellar medium. Scandium has been spectroscopically detected in certain stars, particularly chemically peculiar stars and Ap stars. Its cosmic abundance is relatively low compared to other elements of similar mass such as calcium and titanium. The analysis of scandium in primitive meteorites provides information on the physicochemical conditions during the formation of the solar system. Isotopic ratios of scandium in different celestial bodies help understand stellar nucleosynthesis processes and the chemical evolution of the galaxy.

The development of more abundant and economical sources of scandium is a major strategic challenge for the aerospace and advanced technology industries. Research is underway to extract scandium from bauxite residues (red mud), which contain significant but difficult-to-recover amounts. Recycling used aluminum-scandium alloys is also becoming a priority. Mining projects specifically dedicated to scandium are under development in Australia, Scandinavia, and North America. If the cost of scandium could be reduced by a factor of 10, its use in aluminum alloys would become economically viable on a large scale, potentially revolutionizing the aeronautical and automotive industries with significant energy efficiency gains through weight reduction.

N.B.:

In 1871, Mendeleev had predicted an atomic mass of 44 for his "ekaboron"; scandium actually has an atomic mass of 44.96. He had predicted a density of 3.5 g/cm³; scandium has a density of 2.985 g/cm³. He had predicted the formation of an oxide Eb₂O₃; scandium forms Sc₂O₃. When Per Teodor Cleve compared the properties of the newly discovered scandium to Mendeleev's predictions, the correspondence was so perfect that it astonished the scientific community. This resounding validation transformed the periodic table from a simple classification into a true predictive tool, demonstrating that nature obeys fundamental laws that human intelligence can discover and exploit.