Europium is synthesized in stars almost exclusively by the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during cataclysmic events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. Unlike most light lanthanides, which show significant contributions from the s-process, europium is dominated by about 95% by the r-process, making it one of the purest tracers of this explosive nucleosynthesis process.

The cosmic abundance of europium is about 9.7×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it about 1000 times less abundant than cerium and one of the rarest lanthanides in the universe. This extreme rarity is explained by its almost exclusive production in violent r-process events, which are much less frequent than s-processes in AGB stars. Europium is the signature element of the r-process.

The europium/iron (Eu/Fe) ratio in stars is a critical indicator of the history of galactic chemical enrichment. Old, metal-poor stars show high Eu/Fe ratios, indicating that the first generations of massive supernovae rapidly enriched the Galaxy with r-process elements like europium. Younger stars show lower Eu/Fe ratios, reflecting the increasing contribution of Type Ia supernovae (which do not produce europium) and the progressive chemical evolution of the Galaxy.

Spectroscopic observation of the kilonova GW170817 (a neutron star merger detected in 2017) revealed signatures compatible with the massive synthesis of heavy elements including europium. Theoretical models suggest that this single event produced several Earth masses of europium, confirming that neutron star mergers are major sites for the production of r-process elements. These observations revolutionized our understanding of the cosmic origin of heavy rare earths.

Europium is named after the continent of Europe, following the tradition of naming elements after geographical locations. The name was chosen by its discoverer to honor Europe, the birthplace of many pioneers in rare earth chemistry. Europium is one of the few elements named after a continent rather than a person, a specific place, or a chemical property.

Europium was discovered in 1896 by the French chemist Eugène-Anatole Demarçay (1852-1903) in Paris. Demarçay detected unusual spectral lines in concentrated samarium samples, suggesting the presence of a new element. Using spectroscopy, a technique in which he excelled despite partial blindness following a laboratory explosion, Demarçay gradually isolated the new element through repeated fractional crystallizations of contaminated samarium nitrate.

In 1901, after five years of meticulous work, Demarçay obtained europium samples pure enough for complete characterization. He determined the distinctive spectral properties of europium and demonstrated that it was indeed a new element and not a known impurity. Demarçay's discovery was quickly confirmed by other European chemists. The isolation of pure metallic europium was not achieved until 1937 by electrolytic reduction.

Europium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 2 ppm, making it the 51st most abundant element, comparable to sulfur. It is the least abundant rare earth among the light lanthanides, reflecting its limited astrophysical production by the r-process. The main minerals containing europium are bastnasite ((Ce,La,Nd,Eu)CO₃F), where europium represents about 0.1-0.2% of the rare earth content, and monazite ((Ce,La,Nd,Eu,Th)PO₄), where it represents 0.05-0.1%.

Global production of europium oxides is about 400 to 600 tons per year, making it one of the least produced rare earths. China dominates with about 85-90% of world production, followed by the United States and Australia. Due to its relative rarity and high-value specialized applications, europium is one of the most expensive rare earths, with typical prices of $200-500 per kilogram of oxide, depending on purity and market conditions.

Metallic europium is produced mainly by reducing europium oxide (Eu₂O₃) with metallic lanthanum at high temperature in an inert atmosphere, or by electrolysis of molten europium chloride. Global annual production of metallic europium is about 100-150 tons. Recycling of europium from fluorescent lamps and used screens accounts for about 1-2% of total supply, although recycling rates are gradually improving with advanced separation technologies and economic incentives linked to high prices.

Europium (symbol Eu, atomic number 63) is the seventh element in the lanthanide series, belonging to the rare earths of the f-block of the periodic table. Its atom has 63 protons, usually 90 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{153}\mathrm{Eu}\)) and 63 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁷ 6s².

Europium is the most reactive lanthanide and has remarkably atypical physical properties. It is the softest, most ductile and malleable rare earth metal, and can be easily cut with a knife like sodium. Europium has the lowest density of all lanthanides (5.24 g/cm³), even lower than that of iron. It crystallizes in a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure at room temperature, unlike most lanthanides which adopt hexagonal close-packed structures.

Europium melts at 822 °C (1095 K) and boils at 1529 °C (1802 K), having the lowest melting and boiling points of all lanthanides. This relative volatility paradoxically facilitates its purification by vacuum distillation. Europium is a poor electrical conductor, with conductivity about 50 times lower than that of copper. Europium is paramagnetic at room temperature and exhibits complex magnetic properties at low temperatures.

Europium is extraordinarily reactive, oxidizing rapidly in air to form a yellow-green oxide layer that does not protect the metal. Metallic europium must be stored under mineral oil or in an inert argon atmosphere. It spontaneously ignites in air when finely divided and reacts vigorously with water even at room temperature. Europium burns easily in air with a characteristic bright red-orange flame.

Melting point of europium: 1095 K (822 °C).

Boiling point of europium: 1802 K (1529 °C).

Europium is the most reactive lanthanide, oxidizing rapidly in air and reacting vigorously with water.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europium-151 — \(\,^{151}\mathrm{Eu}\,\) | 63 | 88 | 150.919850 u | ≈ 47.81 % | Stable | Minor stable isotope of europium, representing about 48% of the natural total. |

| Europium-153 — \(\,^{153}\mathrm{Eu}\,\) | 63 | 90 | 152.921230 u | ≈ 52.19 % | Stable | Major stable isotope of europium, representing about 52% of the natural total. |

| Europium-152 — \(\,^{152}\mathrm{Eu}\,\) | 63 | 89 | 151.921745 u | Synthetic | ≈ 13.54 years | Radioactive (EC, β⁻, β⁺). Intense gamma emitter, used for radiation detector calibration. |

| Europium-154 — \(\,^{154}\mathrm{Eu}\,\) | 63 | 91 | 153.922979 u | Synthetic | ≈ 8.59 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Gamma emitter, activation product in nuclear reactors. |

| Europium-155 — \(\,^{155}\mathrm{Eu}\,\) | 63 | 92 | 154.922893 u | Synthetic | ≈ 4.76 years | Radioactive (β⁻). Significant fission product, used in nuclear research. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

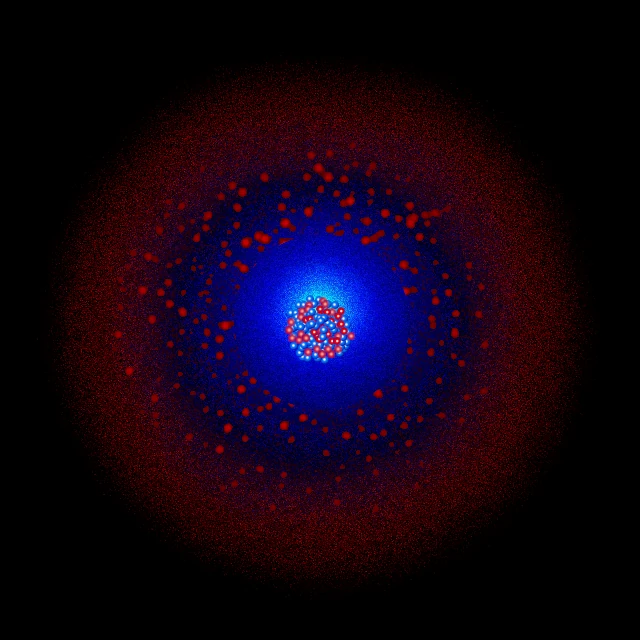

Europium has 63 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f⁷ 6s² is particularly stable due to the half-filled 4f subshell (7 electrons out of 14 possible), providing additional stability according to Hund's rule. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(25) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f⁷ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable and complete structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 25 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f⁷ 5d⁰. The seven half-filled 4f electrons characterize the chemistry of europium.

P shell (n=6): contains 2 electrons in the 6s² subshell. These electrons are the outer valence electrons of europium.

Europium effectively has 9 valence electrons: seven 4f⁷ electrons and two 6s² electrons. Europium exhibits two stable oxidation states: +2 and +3. The +3 state is the most common, where europium loses its two 6s electrons and one 4f electron to form the Eu³⁺ ion with the configuration [Xe] 4f⁶. This ion is responsible for the intense red luminescence that makes europium famous.

The +2 state is unusual among lanthanides but particularly stable for europium due to the half-filled 4f⁷ configuration of the Eu²⁺ ion (configuration [Xe] 4f⁷). This exceptional stability allows the existence of many europium(II) compounds: EuO (oxide), EuCl₂ (chloride), EuSO₄ (sulfate), and various halides. Europium(II) also exhibits luminescent properties, typically emitting in the blue-green.

The ease with which europium oscillates between the +2 and +3 states makes it an excellent redox indicator. In aqueous solution, europium(II) is a moderately strong reducing agent and gradually oxidizes to europium(III) in the presence of oxygen. This rich redox chemistry distinguishes europium from other light lanthanides and brings it closer to alkaline earth metals such as barium and strontium in some aspects of its chemistry.

Europium is extremely reactive with oxygen and oxidizes rapidly in air, forming a yellow-green layer of Eu₂O₃ (europium(III) oxide) that cracks and flakes continuously, offering no protection to the underlying metal. Finely divided europium spontaneously ignites in air and reacts vigorously with water even at room temperature. Europium burns easily in air with a characteristic bright red-orange flame: 4Eu + 3O₂ → 2Eu₂O₃. Fine europium powder is pyrophoric and must be handled in an inert atmosphere.

Europium reacts vigorously with water at room temperature, producing europium(III) hydroxide and releasing hydrogen gas with visible effervescence: 2Eu + 6H₂O → 2Eu(OH)₃ + 3H₂↑. This reaction is exothermic and accelerates rapidly; the released hydrogen can spontaneously ignite with sufficiently large samples. Europium(III) hydroxide precipitates as a gelatinous pink-white solid. The reaction of europium with water is among the most vigorous of all lanthanides.

Europium reacts vigorously with all halogens to form trihalides: 2Eu + 3Cl₂ → 2EuCl₃. Europium(II) dihalides can be prepared by reducing trihalides with metallic europium: Eu + 2EuCl₃ → 3EuCl₂. Europium dissolves rapidly in acids, even dilute ones, with vigorous hydrogen evolution: 2Eu + 6HCl → 2EuCl₃ + 3H₂↑, producing pale yellow solutions of Eu³⁺.

Europium reacts with hydrogen at moderate temperatures to form EuH₂ hydride, with sulfur to form EuS sulfide (an interesting magnetic semiconductor), with nitrogen at high temperatures to form EuN nitride, and with carbon to form EuC₂ and Eu₂C₃ carbides. Europium also forms many organometallic and coordination complexes, exploited in catalysis and synthetic chemistry.

The most remarkable property of europium is its intense luminescence. The Eu³⁺ ion is one of the most luminescent lanthanide ions, emitting pure red light around 610-630 nm (⁵D₀ → ⁷F₂ transition) when excited by UV or cathode rays. This intense red emission with high quantum yield (up to 90% in optimized matrices) makes europium the standard red phosphor for all display and lighting applications. The Eu²⁺ ion emits in the blue-green (450-550 nm) with remarkable efficiency as well.

The application that made europium famous was its use as a red phosphor in cathode ray tube (CRT) screens for televisions and computer monitors from 1960 to 2000. The Y₂O₃:Eu³⁺ phosphor (yttrium oxide doped with 5-10% europium) produced pure red emission at 611 nm with exceptional efficiency when bombarded with electrons. Combined with green (ZnS:Cu,Al) and blue (ZnS:Ag) phosphors, it enabled full color spectrum reproduction. A typical CRT television contained 0.5-2 grams of europium in its phosphorescent coating.

With the decline of CRT screens in the early 2000s, europium found new applications in modern LCD screens. The white LED backlights of LCD screens use europium phosphors to convert some of the blue LED light into red light, creating balanced white light. Typical phosphors include (Sr,Ca)AlSiN₃:Eu²⁺ (nitridosilicate emitting red-orange) or CaAlSiN₃:Eu²⁺. This application now accounts for 50-60% of global europium demand.

Europium phosphors are crucial for achieving a wide color gamut in modern displays. Without europium, LCD screens would have poor red color reproduction, particularly affecting skin tones and saturated images. Recent "quantum dot" displays also use europium-containing phosphors to further improve color quality. The exceptional spectral purity of Eu³⁺ emission (line width 5-10 nm) enables vivid, saturated colors impossible to achieve with other phosphors.

Europium plays an essential role in energy-saving fluorescent lamps and "tri-phosphor" fluorescent tubes that produce high-quality white light. These lamps use a mixture of three phosphors: blue (BaMgAl₁₀O₁₇:Eu²⁺), green (LaPO₄:Ce³⁺,Tb³⁺), and red (Y₂O₃:Eu³⁺). The red europium phosphor is absolutely indispensable for achieving a high color rendering index (CRI) above 80-85, essential for quality residential and commercial lighting.

Tri-phosphor lamps containing europium convert the UV emission of mercury (254 nm) into visible light with an efficiency of 25-30%, 3-4 times higher than incandescent halogen lamps. A typical 20W compact fluorescent lamp contains about 10-20 milligrams of europium. The color temperature can be adjusted from "warm white" (2700K) to "cool white" (6500K) by varying the relative proportions of the three phosphors.

The use of europium in fluorescent lamps peaked around 2005-2010 and then gradually declined with the massive adoption of LEDs. Modern white LEDs also use europium phosphors, but in smaller quantities (1-5 mg per LED) because they are more efficient. This transition caused a temporary oversupply of europium on the global market in 2010-2015, followed by a rebalancing with the growth of LCD and LED screens.

Europium is widely used in luminescent inks and pigments for the security of banknotes, passports, identity cards, and official documents. Organometallic europium complexes incorporated into inks exhibit intense red luminescence under UV illumination (365 nm or 254 nm), allowing quick verification of authenticity. The euro, US dollar, Japanese yen, and most major currencies use europium markers.

Modern security applications use sophisticated mixtures of europium complexes with different persistent luminescence times (from microseconds to seconds), different emission wavelengths, and different spectral responses. These complex spectral signatures are extremely difficult for counterfeiters to reproduce. Some banknotes use "converting phosphors" where europium emits at a different wavelength than the excitation, creating a visible color change.

Beyond banknotes, europium is used to mark authentic pharmaceutical products, original automotive parts, works of art, credit cards, event tickets, and various luxury goods. Europium-doped nanoparticles allow micrometric marking invisible to the naked eye but detectable by fluorescence. Europium complexes are also used as tracers in hydrology to study underground flows and identify sources of pollution.

The isotopes Eu-151 and Eu-153 have exceptionally high thermal neutron absorption cross sections (9200 barns and 312 barns respectively), making europium an excellent neutron absorber for nuclear reactors. Europium oxide (Eu₂O₃) is incorporated into some control rods and regulation plates to control reactor reactivity. Europium is particularly useful in research reactors requiring precise reactivity control.

Europium is used as a "burnable poison" in some nuclear fuels to compensate for excess reactivity at the beginning of the cycle. As Eu-151 absorbs neutrons, it transforms into Eu-152 and then Eu-153, automatically maintaining reactivity within safe limits during the progressive consumption of the fuel. This self-regulating property improves safety and allows longer fuel cycles without intervention.

Europium and its stable compounds have low chemical toxicity, similar to other light lanthanides. Soluble europium compounds can cause skin, eye, and respiratory tract irritation upon direct exposure. Inhalation of europium dust can cause transient pulmonary irritation. Toxicological studies show moderate acute toxicity, with LD50 (median lethal dose) for europium salts typically above 500-1000 mg/kg in rodents.

Ingested or inhaled europium accumulates mainly in the liver, spleen, and bone skeleton. The biological half-life is estimated at 3-5 years for bone europium and 1-2 years for soft tissues. At high doses, europium can disrupt calcium metabolism and cause moderate hepatic toxicity. However, significant human exposure to europium remains rare, limited to workers in the rare earth industry and phosphor manufacturing. No carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic effects have been demonstrated for stable europium.

The radioactive isotopes of europium (Eu-152, Eu-154, Eu-155) produced by neutron activation in nuclear reactors pose a significant radiological risk due to their intense gamma emissions. Eu-152 is particularly concerning as it emits gamma rays of multiple energies requiring appropriate shielding. Workers handling these isotopes must use radiation protection and comply with regulatory exposure limits. The relatively long radioactive half-life of Eu-152 (13.5 years) requires prolonged storage of contaminated waste.

The environmental concerns associated with europium mainly concern the mining of rare earths. Since europium is particularly rare in ores (0.05-0.2%), the extraction of one kilogram of europium requires the processing of several tons of ore, generating significant volumes of acidic waste, contaminated sludge, and liquid discharges. Rare earth mining sites can contaminate soils and waters with radioactive elements (thorium, uranium) naturally present in monazite ores.

Recycling europium from fluorescent lamps and used screens is technically feasible and economically attractive due to the high prices of europium. Recycling processes involve crushing fluorescent tubes, separating phosphors, acid dissolution, and selective extraction of europium by chromatography or solvent extraction. Current recycling rates are about 1-2% but are gradually improving with electronic waste regulations and economic incentives.

Recycling one ton of fluorescent lamps can recover about 100-200 grams of europium, representing a value of $20-100 depending on market prices. Challenges include the efficient collection of used lamps, separation of mixed phosphors, and purification to acceptable levels for reuse. Improving europium recycling infrastructure is crucial to reduce dependence on primary supplies concentrated in China and mitigate the environmental impacts of mining.

Occupational exposure to europium occurs mainly in rare earth refining industries, phosphor manufacturing, and fluorescent lamp recycling. Occupational exposure standards for europium compounds are not specifically established in most jurisdictions, but general recommendations for soluble rare earth compounds typically set exposure limits at 5-10 mg/m³ for respirable dust. Europium concentrations in industrial environments can reach several milligrams per cubic meter of air, requiring appropriate ventilation and respiratory protective equipment.