Cesium is a rare element in the universe, primarily produced by stellar nucleosynthesis during the advanced stages of stellar evolution. As a heavy element with atomic number 55, cesium requires neutron capture processes to be synthesized, making it much less abundant than lighter elements such as hydrogen, helium, carbon, or oxygen.

Cesium is mainly produced by two nucleosynthesis processes: the s process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars and the r process (rapid neutron capture) during supernova explosions and neutron star mergers. In the s process, barium and lanthanum nuclei gradually capture neutrons to form cesium in the outer layers of AGB stars, where thermal pulses create favorable conditions. The r process, occurring in cataclysmic environments with extremely high neutron flux, rapidly produces neutron-rich isotopes that subsequently decay to stable \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Cs}\). These stars enrich the interstellar medium with cesium through their intense stellar winds and supernova ejecta.

In the interstellar medium, cesium exists mainly in neutral or ionized atomic form (Cs, Cs⁺). Due to its low ionization potential (the lowest of all stable elements), cesium is easily ionized by ambient ultraviolet radiation in low-density regions. Atomic cesium has been detected in some cool stars and in the spectra of a few dense interstellar clouds through its characteristic absorption lines. Unlike lighter elements, cesium does not form stable molecules under typical interstellar conditions, although cesium hydrides (CsH) could theoretically exist in very cold and dense environments.

Cesium has only one natural stable isotope, \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Cs}\), which accounts for 100% of natural cesium. However, several radioactive isotopes of cesium are naturally produced by nuclear fission processes and the decay of heavier elements. \(\,^{137}\mathrm{Cs}\) (half-life of 30.17 years) and \(\,^{134}\mathrm{Cs}\) (half-life of 2.06 years) are significant fission products that serve as tracers for dating sediments, studying soil erosion, and detecting anthropogenic radioactive contamination (nuclear tests, nuclear accidents). The presence of these isotopes in the environment provides a precise temporal signature of nuclear events from the 20th and 21st centuries.

In planetary systems, cesium is present in trace amounts in rocks and minerals. On Earth, cesium is concentrated in certain minerals such as pollucite (an aluminum and cesium silicate), which is the main commercial source of cesium. Due to its high ionic radius and unique charge, cesium behaves as an incompatible element in geochemistry, preferentially enriching in magmatic liquids during differentiation and concentrating in granitic pegmatites. The study of cesium distribution in terrestrial and meteoritic rocks helps understand planetary differentiation processes and the evolution of the continental crust.

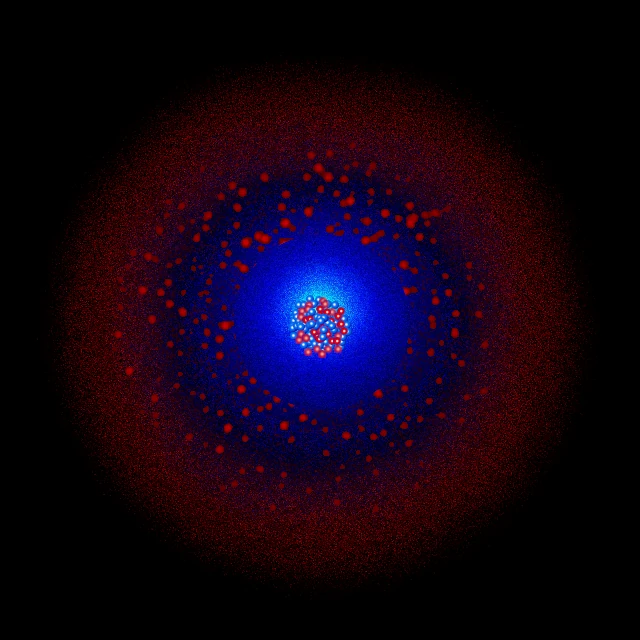

Cesium was discovered in 1860 by German chemists Robert Bunsen (1811-1899) and Gustav Kirchhoff (1824-1887) at the University of Heidelberg. This remarkable discovery was made possible by the new technique of spectroscopy they had developed, allowing the identification of chemical elements by their characteristic spectral lines. By analyzing the mineral water from Dürkheim with a spectroscope, they observed two intense bright blue lines (at 455.5 nm and 459.3 nm) that did not correspond to any known element. These distinct blue lines allowed them to isolate a new alkali element, which they named cesium, from the Latin caesius meaning "sky blue," in reference to the characteristic color of its spectral lines.

Bunsen isolated pure cesium metal in 1881 by electrolysis of molten cesium cyanide, revealing an extremely soft metal with a golden-silver color that melts at just 28.5 °C (just above room temperature). The discovery of cesium marked a triumph of analytical spectroscopy and demonstrated the power of this new method to identify elements present in minute quantities. The following year, in 1861, Bunsen and Kirchhoff also discovered rubidium using the same spectroscopic technique.

N.B.:

Cesium-133 plays a fundamental role in the modern definition of time. Since 1967, the second, the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), has been defined by the frequency of the hyperfine transition of the cesium-133 atom: one second corresponds exactly to 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation emitted during this transition. Cesium atomic clocks, developed in the 1950s, exploit this extremely stable transition to measure time with extraordinary precision (a few seconds of error over millions of years). These clocks constitute the global reference for International Atomic Time (TAI) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), synchronizing GPS navigation systems, telecommunications, electrical networks, and financial transactions. The most advanced cesium atomic clocks (atomic fountains) now achieve uncertainties of less than one second over 300 million years, making cesium the ultimate keeper of our time measurement.

Cesium (symbol Cs, atomic number 55) is an alkali metal in group 1 of the periodic table, consisting of fifty-five protons, usually seventy-eight neutrons (for the single stable isotope), and fifty-five electrons. The only natural stable isotope is cesium-133 \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Cs}\) (100% natural abundance).

At room temperature, cesium is a soft metal with a golden-silver color, soft enough to be cut with a knife like butter. Cesium has the lowest melting point of all metals except mercury and gallium, melting at just 28.5 °C. In warm weather, cesium can therefore be liquid at room temperature. It is also the most reactive and electropositive alkali metal, reacting violently and exploding on contact with cold water and even ice. Metallic cesium has a density of about 1.93 g/cm³, making it a relatively light metal despite its high atomic number. The temperature at which liquid and solid states can coexist (melting point): 301.59 K (28.44 °C). The temperature at which it transitions from liquid to gas (boiling point): 944 K (671 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cesium-133 — \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Cs}\,\) | 55 | 78 | 132.905452 u | 100% | Stable | Only stable isotope; used in atomic clocks to define the second (9,192,631,770 Hz). |

| Cesium-134 — \(\,^{134}\mathrm{Cs}\,\) | 55 | 79 | 133.906718 u | Not natural | 2.0648 years | Radioactive ß\(^-\) and γ; fission and neutron activation product; gamma emitter used in nuclear medicine and to trace nuclear accidents. |

| Cesium-135 — \(\,^{135}\mathrm{Cs}\,\) | 55 | 80 | 134.905977 u | Not natural | 2.3 million years | Radioactive ß\(^-\); long-lived fission product; important in nuclear waste management. |

| Cesium-137 — \(\,^{137}\mathrm{Cs}\,\) | 55 | 82 | 136.907089 u | Not natural | 30.17 years | Radioactive ß\(^-\) and γ; major fission product (~6%); major environmental tracer; used in radiotherapy and sediment dating; significant concern in nuclear accidents (Chernobyl, Fukushima). |

| Other isotopes — \(\,^{112}\mathrm{Cs}-\,^{132}\mathrm{Cs},\,^{136}\mathrm{Cs},\,^{138}\mathrm{Cs}-\,^{151}\mathrm{Cs}\) | 55 | 57-77, 81, 83-96 | — | Not natural | microseconds — 13 days | Artificially produced radioactive isotopes; used in nuclear research; some are produced in reactors and nuclear explosions. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons organize around the nucleus.

Cesium has 55 electrons distributed across six electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p⁶ 6s¹, or simplified: [Xe] 6s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(8) P(1).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶, forming a complete and stable shell.

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰, forming a complete shell.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰, forming a complete shell.

O shell (n=5): contains 8 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶, forming a complete shell.

P shell (n=6): contains only 1 electron in the 6s subshell. This single valence electron, far from the nucleus and strongly shielded by the inner shells, is extremely weakly bound and easily lost, explaining the exceptional reactivity of cesium.

Cesium, a member of group 1 (alkali metals), has 1 single valence electron (6s¹) in its outer shell. This electron is the farthest from the nucleus of all stable elements, with the largest atomic radius (about 265 pm) and the lowest ionization potential (3.89 eV), making cesium the most electropositive and reactive of all stable metals. The 6s electron is so weakly bound that it is easily removed, forming the Cs⁺ ion with a stable xenon-like electronic configuration. This property explains cesium's extreme reactivity with water, oxygen, and even ice.

Cesium has highly specialized and strategic applications. Its most important use is in cesium-133 atomic clocks, where the hyperfine transition of \(\,^{133}\mathrm{Cs}\) defines the second and forms the basis of International Atomic Time. Cesium photocells exploit its low ionization potential to detect infrared light. Cesium is used in space ion propulsion systems, as a catalyst in organic chemistry, in high-density oil drilling fluids (cesium formate), and in special glasses. Radioactive \(\,^{137}\mathrm{Cs}\) is used in radiotherapy, industrial sterilization, and as an environmental tracer to study erosion and sedimentation.

Cesium has a single valence electron (6s¹) that is the most loosely bound of all stable elements due to its large atomic radius (the largest of all elements) and the significant shielding effect of many inner electron shells. Its first ionization energy (3.89 eV) is the lowest of all stable elements, making cesium the most electropositive and chemically reactive element. Cesium easily loses its valence electron to form the Cs⁺ ion with a stable xenon-like electronic configuration. This extreme ease of losing an electron explains its explosive reactivity with water, even with ice at -116 °C.

Cesium reacts violently and spontaneously with water and atmospheric moisture, producing cesium hydroxide (CsOH) and hydrogen gas with enough heat to ignite the gas and cause an explosion. The reaction is so violent that metallic cesium must be stored under mineral oil or in a sealed ampoule under an inert atmosphere (argon). Cesium also reacts rapidly with oxygen to form various oxides: cesium oxide Cs₂O, peroxide Cs₂O₂, and especially superoxide CsO₂. Cesium forms ionic compounds with almost all non-metals: cesium halides (CsF, CsCl, CsBr, CsI), sulfide Cs₂S, nitride Cs₃N, and carbide Cs₂C₂. Cesium hydroxide (CsOH) is the strongest known base, even surpassing sodium and potassium hydroxides in basicity.

Metallic cesium has exceptional physical properties. It is the stable metal with the lowest melting point after mercury (28.44 °C), melting almost at room temperature. It is extremely soft, easily cut with a knife, and has a characteristic silver color with golden reflections. Its relatively low density (1.93 g/cm³) for such a heavy element is due to its large atomic size and loosely packed body-centered cubic crystal structure. Cesium has high electrical conductivity and one of the highest thermal expansion coefficients of all metals.