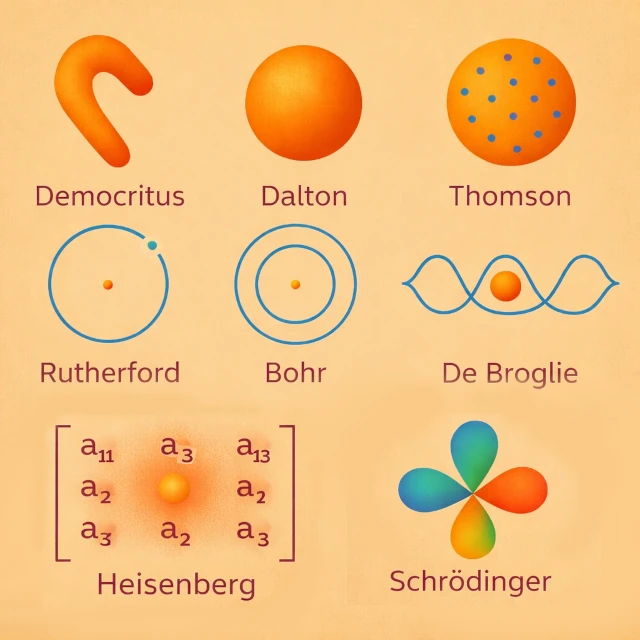

The concept of the atom first appeared in the 5th century BCE with Democritus (c. 460-370 BCE), who postulated, through an essentially intuitive and rational approach, the existence of indivisible particles moving in a void. This proposal was not based on experimental observation, but on a philosophical intuition aimed at resolving the problem of the infinite divisibility of matter. No experiment could then test this hypothesis. The atom was thus conceived as the ultimate unit of matter, without internal structure or measurable properties. For Democritus, the atom had its own shape, which intuitively explained the properties of bodies: for example, hooked atoms interlock and create rough textures, while round or smooth atoms produce fluid or soft substances.

In the Middle Ages, there was no physical modeling of the atom in the scientific sense, as European natural thought was largely dominated by the legacy of Aristotle, for whom matter is continuous, infinitely divisible, and structured by the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire). This view excluded the existence of indivisible material units and explicitly opposed ancient atomism. However, in the medieval Islamic world, some currents of rational theology, notably kalām, developed a form of philosophical atomism in which the world is composed of discrete atoms recreated at every instant by divine will. This medieval atomism was based neither on experience nor on mathematical laws, but on a metaphysical intuition aimed at reconciling causality, contingency, and divine omnipotence. Thus, during the Middle Ages, the atom persisted as a speculative or theological concept, without becoming an object of physical description or measurement.

At the beginning of the 19th century CE, John Dalton (1766-1844) introduced an atomic theory based on quantitative chemistry. Atoms became chemical and measurable entities, characterized by their mass, and responsible for the laws of conservation. Each chemical element is made up of identical atoms, distinct from those of other elements. For example, in the formation of water, Dalton explained that each molecule results from the combination of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom (H₂O), in accordance with simple and constant proportions. This experimental observation illustrates how atoms govern chemical reactions and their proportions. Visually, one can imagine that Dalton thought of the atom as a compact and homogeneous sphere, without internal structure, just as "a small ball of matter."

The end of the 19th century CE marked a decisive break in the conception of the atom. In 1897, Joseph John Thomson (1856-1940) discovered the electron, demonstrating that the atom is not indivisible. He then proposed a model in which electrons, carriers of negative charge, are dispersed in a diffuse sphere of positive charge, like raisins in a pudding. This model explained certain electrical properties of atoms, but did not account for the stability of the nucleus observed later.

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) interpreted the alpha particle scattering experiment. He demonstrated that the positive charge and most of the mass of the atom are concentrated in a compact central nucleus. Electrons orbit around this nucleus, and the atom becomes a system mostly made up of empty space. This model corrected the limitations of Thomson's model and laid the foundations for subsequent quantum developments.

The classical planetary model is unstable according to electromagnetism, because in classical physics, an accelerated charge such as an electron in orbit radiates electromagnetic energy, gradually loses its kinetic energy, and inevitably spirals toward the nucleus. To resolve this contradiction, Niels Bohr (1885-1962) introduced quantized electron orbits in 1913. Electrons can only occupy certain energy levels, explaining the discrete atomic spectra.

At the beginning of the 20th century CE, Louis de Broglie (1892-1987) proposed a conceptual revolution: the electron, and more generally any material particle, has both a "particle" and a "wave" nature. This idea, called wave-particle duality, suggests that the electron orbiting the nucleus can be described as a "standing wave," whose wavelength is inversely proportional to its momentum: \( \lambda = h / p \), where \( \lambda \) is the wavelength, \( h \) is Planck's constant, and \( p \) is the momentum.

De Broglie's model explains why only certain orbits are stable in Bohr's atom: the electron can only occupy orbits for which its wavelength forms a complete cycle around the nucleus, creating a resonance condition. This concept was an essential step toward "quantum mechanics," as it linked the corpuscular properties of particles to their wave behavior, paving the way for Schrödinger's equation.

In the 1920s CE, Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976) proposed a new approach to the atom based on the principles of quantum mechanics. His model, called "matrix quantum mechanics," did not seek to describe the trajectory of electrons around the nucleus, but only the "observable quantities" such as the energies of atomic levels and the probabilities of transitions between them. Heisenberg introduced the famous "uncertainty principle," which states that it is impossible to know simultaneously and precisely both the position and the momentum of an electron (\( \Delta x \, \Delta p \ge \hbar / 2 \)).

This model radically transformed the understanding of the atom: electrons were no longer seen as particles described by classical orbits, but as entities whose behavior could only be expressed in terms of measurable quantities. Heisenberg's model is very abstract and does not lend itself to a classical illustration of electrons in orbit, unlike Bohr's. But it can still be represented symbolically and pedagogically.

In the early 1920s CE, classical physics could no longer explain the stability of atoms or the discrete spectra observed experimentally. Erwin Schrödinger (1887-1961) then developed a mathematical approach based on wave mechanics. He replaced fixed electron trajectories with a wave function, whose squared modulus indicates the probability of the electron's presence in space.

This approach describes electrons as "probability clouds" organized into atomic orbitals, characterized by quantum numbers defining energy, shape, and orientation. Schrödinger's model accounts for the stability of atoms, atomic spectra, and serves as the foundation for all modern quantum chemistry.

N.B.:

Unlike classical models, the electron does not have a defined trajectory. Quantum mechanics only describes probabilities of presence and energy.

| Model | Scientist | Period | Main Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indivisible Atom | Democritus (c. 460-370 BCE) | 5th century BCE | Particle without internal structure |

| Chemical Atom | John Dalton (1766-1844) | 19th century CE | Defined mass, basis of chemical reactions |

| Thomson's Model | Joseph John Thomson (1856-1940) | Late 19th century CE | Electrons embedded in a diffuse positive charge |

| Nuclear Model | Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) | Early 20th century CE | Central nucleus and peripheral electrons |

| Quantized Model | Niels Bohr (1885-1962) | Early 20th century CE | Discrete energy levels |

| Wave Model | Louis de Broglie (1892-1987) | 20th century CE | Wave-particle duality applied to the electron |

| Matrix Model | Werner Heisenberg (1901-1976) | 20th century CE | Observable quantities, uncertainty principle, indeterminate trajectories |

| Quantum Model | Erwin Schrödinger (1887-1961) | 20th century CE | Wave function and probability orbitals |