Mercury is a volatile element whose synthesis mainly involves the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. It belongs to the so-called "moderately volatile" elements, meaning it condenses at relatively low temperatures during planet formation. This volatility partly explains its distribution in the solar system: it is significantly depleted in terrestrial planets (such as Earth) compared to solar abundances, as much of it remained gaseous during accretion and was blown away by the young Sun.

The cosmic abundance of mercury is about 1.5×10⁻¹¹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it comparable to selenium and bromine. On Earth, it is relatively rare in the crust (about 0.08 ppm). Its presence on other bodies is intriguing: the planet Mercury (which only shares its name by coincidence) has an exosphere containing traces of atomic mercury, probably released by micrometeorite impacts on its surface. Comets and some ice-rich asteroids may also contain mercury in the form of organomercury compounds or sulfides.

On Earth, mercury follows a complex cycle involving the atmosphere, oceans, crust, and biosphere. Its elemental form (Hg⁰) is volatile and can travel long distances in the atmosphere before being oxidized and deposited. This global atmospheric transport explains why mercury pollution is a worldwide problem, affecting even the most remote regions such as the Arctic. The study of ice cores allows us to trace the history of mercury emissions linked to human activities (mining, coal combustion) over millennia.

Mercury anomalies have been identified in marine sediments at the boundary of several mass extinction events (Permian-Triassic, Triassic-Jurassic, Cretaceous-Paleogene). These peaks could be linked to massive volcanic activity (traps) that released enormous amounts of volatile mercury into the atmosphere, contributing to the poisoning of ecosystems. Thus, mercury also serves as a geological tracer of major environmental upheavals of the past.

The chemical symbol Hg comes from the Latin "hydrargyrum", itself derived from the ancient Greek ὕδωρ ἄργυρος (hýdōr árgyros), meaning "liquid silver". This name perfectly describes its appearance: a metal as shiny as silver, but liquid. The French name "mercure" comes from the Roman god Mercury (Hermes to the Greeks), the swift messenger of the gods, perhaps in reference to the mobility and volatility of the liquid metal.

Native mercury (in the form of cinnabar, HgS) has been known since antiquity. The Chinese and Egyptians used it as a vermilion pigment and in medicine (often with disastrous consequences). Alchemists attached primordial importance to mercury, which they considered, along with sulfur and salt, as one of the three fundamental principles of matter. They believed it was the key to transmuting metals into gold. Its ability to dissolve gold (forming amalgam) and to evaporate and recondense intact fascinated minds and fueled mystical theories.

In the 18th century, mercury played a crucial role in the development of thermometry (Fahrenheit and Celsius thermometers) and barometry (Torricelli's experiment, 1643, which demonstrated the existence of atmospheric pressure using a column of mercury). The discovery of its toxic compounds, such as calomel (Hg₂Cl₂) and corrosive sublimate (HgCl₂), also marked the beginnings of pharmaceutical and industrial chemistry.

The main source of mercury is cinnabar (mercury(II) sulfide, HgS), a scarlet red ore. Major deposits have been exploited in Almadén (Spain, the largest historical mine), Idrija (Slovenia), and Monte Amiata (Italy). Today, primary mining production has significantly decreased due to toxicity and environmental restrictions. China and Kyrgyzstan are among the last significant producers.

Most of the mercury circulating today comes from recycling or is a by-product of other activities:

Due to its toxicity, mercury trade is strictly regulated by the Minamata Convention (2013).

Mercury (symbol Hg, atomic number 80) is a transition metal of the 6th period, located in group 12 of the periodic table, along with zinc and cadmium. Its atom has 80 protons, usually 122 neutrons (for the stable isotope \(^{202}\mathrm{Hg}\)) and 80 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s². This configuration with a complete d¹⁰ shell and a complete s² shell is similar to that of noble gases, contributing to its low reactivity in metallic form and its low melting point.

Mercury is the only metal liquid at room temperature and pressure. It is a dense, silvery-white, mobile liquid that easily divides into spherical droplets.

In solid state, mercury is malleable and ductile and crystallizes in a rhombohedral structure.

Mercury freezes at -38.8290 °C (234.321 K) and boils at 356.73 °C (629.88 K). Its wide liquid temperature range (nearly 400°C) and its linear expansion made it successful in measuring instruments.

Mercury is a relatively noble metal. It does not react with non-oxidizing acids (dilute HCl, dilute H₂SO₄) but dissolves in nitric acid and aqua regia. It resists oxidation by air at room temperature, but slowly forms a gray oxide film in the presence of ozone. It reacts with halogens, sulfur, and metals to form amalgams.

State at 20°C: Liquid.

Melting point: 234.321 K (-38.8290 °C).

Boiling point: 629.88 K (356.73 °C).

Density: 13.534 g/cm³.

Electronic configuration: [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s².

Main oxidation states: +1 and +2.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury-196 — \(^{196}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 116 | 195.96583 u | ≈ 0.15 % | Stable | Rare stable isotope. |

| Mercury-198 — \(^{198}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 118 | 197.966769 u | ≈ 9.97 % | Stable | Stable isotope. |

| Mercury-199 — \(^{199}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 119 | 198.968280 u | ≈ 16.87 % | Stable | Stable isotope with nuclear spin I=1/2, used in \(^{199}\mathrm{Hg}\) NMR spectroscopy. |

| Mercury-200 — \(^{200}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 120 | 199.968326 u | ≈ 23.10 % | Stable | Stable isotope. |

| Mercury-201 — \(^{201}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 121 | 200.970302 u | ≈ 13.18 % | Stable | Stable isotope. |

| Mercury-202 — \(^{202}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 122 | 201.970643 u | ≈ 29.86 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope. |

| Mercury-204 — \(^{204}\mathrm{Hg}\) | 80 | 124 | 203.973494 u | ≈ 6.87 % | Stable | Stable isotope. |

N.B.:

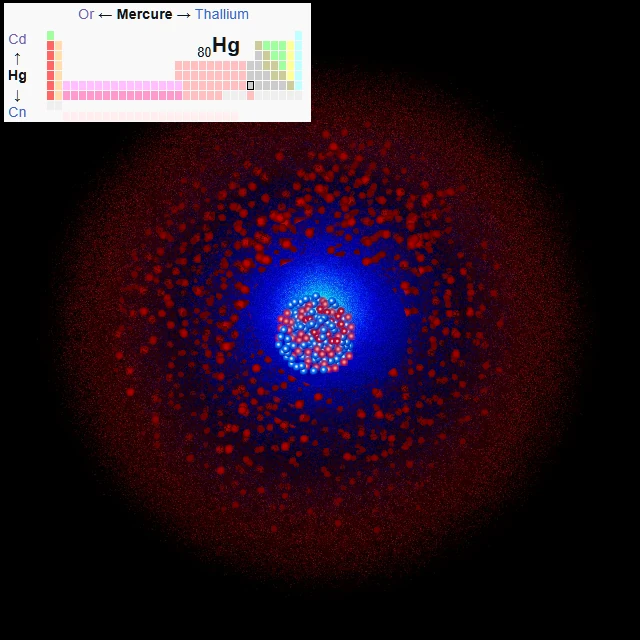

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Mercury has 80 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s² has a completely filled 5d shell (10 electrons) and a complete 6s shell (2 electrons), similar to the configuration of a noble gas. This can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(32) O(18) P(2), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰ 6s².

K shell (n=1): 2 electrons (1s²).

L shell (n=2): 8 electrons (2s² 2p⁶).

M shell (n=3): 18 electrons (3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰).

N shell (n=4): 32 electrons (4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴).

O shell (n=5): 18 electrons (5s² 5p⁶ 5d¹⁰).

P shell (n=6): 2 electrons (6s²).

Mercury has 2 valence electrons (6s²). However, due to the inert pair effect (particular stability of the 6s² electron pair), mercury exhibits a particular chemistry with two stable oxidation states: +1 and +2.

Metallic mercury (Hg⁰) is relatively unreactive due to the strength of the Hg-Hg bond in the liquid and the high energy required to promote a 6s electron to a higher level.

Metallic mercury does not oxidize in air at room temperature. When slowly heated to its boiling point, it eventually forms red mercury(II) oxide (HgO): 2Hg + O₂ → 2HgO. This oxide decomposes back into mercury and oxygen above 400°C. In the presence of ozone, a gray oxide film forms on the surface.

N.B.:

This is a characteristic property: mercury dissolves many other metals (gold, silver, tin, zinc, sodium) to form amalgams, which are alloys in liquid or pasty state. The gold-mercury amalgam has been widely used in artisanal gold extraction (garimpos). The silver-tin-mercury amalgam was the basis of dental "fillings". Sodium or potassium amalgams are used as powerful reducing agents in organic chemistry.

The toxicity of mercury depends strongly on its chemical form:

In case of metallic mercury spillage, it is necessary to ventilate intensively, avoid walking on it (to prevent spreading droplets), and use a specific trap (syringe, pipette, sulfur powder) to collect it. Never use a vacuum cleaner (it vaporizes and disperses mercury). Exposure requires urgent medical consultation. Treatment of acute poisoning may use chelators such as DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid) or DMPS, which bind to mercury and promote its urinary excretion.

Mercury is a persistent pollutant that follows a complex cycle:

Mercury pollution affects wildlife (reduced reproduction in fish-eating birds, neurological disorders in marine mammals). For humans, the main route of exposure is the consumption of contaminated fish. The most at-risk populations are coastal communities, indigenous peoples (Inuit), and pregnant women (methylmercury crosses the placenta and harms fetal neurological development).

The Minamata Convention on Mercury, adopted in 2013 and entered into force in 2017, is an international treaty aimed at protecting human health and the environment. It requires:

Given the toxicity and persistence of mercury, it is imperative to recover and isolate it from the biosphere permanently. Mercury cannot be "destroyed" (the atoms persist), but it can be stabilized in less dangerous forms.

The main challenges are the phase-out of the last uses (certain chemical processes, certain lamps), the remediation of contaminated sites (former factories, mines), and the management of mercury present in products in circulation (millions of thermometers and dental amalgams). Research continues on biological decontamination methods (phytoremediation) and on non-toxic alternatives in all areas where mercury was historically used.