Calcium compounds have been used since ancient times, although the element itself was not suspected to exist. The Romans produced quicklime (calcium oxide, CaO) by heating limestone to make mortar and cement. In 1808, Humphry Davy (1778-1829), a few months after isolating sodium and potassium, succeeded in isolating metallic calcium by electrolysis of a moistened mixture of calcium oxide and mercury oxide. Davy named this new metal calcium, from the Latin calx = lime, a term already used by the Romans to refer to calcined limestone. However, pure metallic calcium was difficult to obtain and preserve due to its high reactivity. It was not until 1898 that Henri Moissan (1852-1907) improved the isolation process by electrolysis of molten calcium chloride, making it possible to obtain relatively pure calcium.

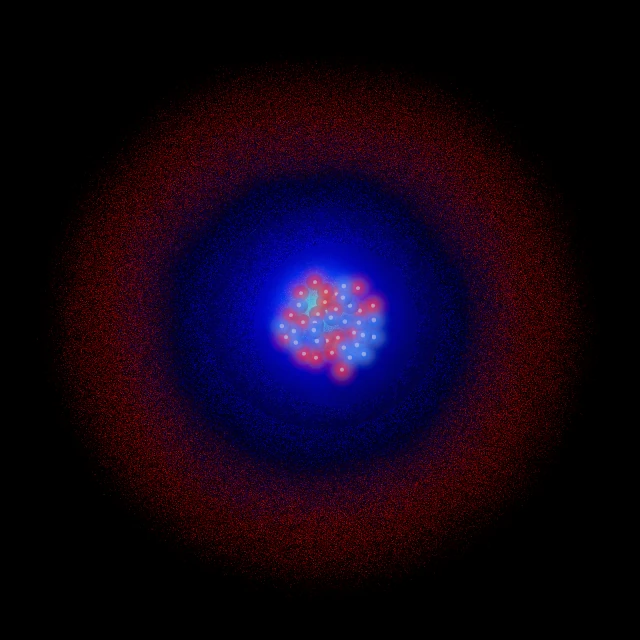

Calcium (symbol Ca, atomic number 20) is an alkaline earth metal in group 2 of the periodic table. Its atom has 20 protons, 20 electrons, and usually 20 neutrons in its most abundant isotope (\(\,^{40}\mathrm{Ca}\)). Six stable isotopes exist: calcium-40 (\(\,^{40}\mathrm{Ca}\)), calcium-42 (\(\,^{42}\mathrm{Ca}\)), calcium-43 (\(\,^{43}\mathrm{Ca}\)), calcium-44 (\(\,^{44}\mathrm{Ca}\)), calcium-46 (\(\,^{46}\mathrm{Ca}\)), and calcium-48 (\(\,^{48}\mathrm{Ca}\)).

At room temperature, calcium is a solid, silvery-white metal, relatively soft (can be cut with a knife). Density ≈ 1.54 g/cm³. Melting point of calcium: 1,115 K (842 °C). Boiling point: 1,757 K (1,484 °C). Metallic calcium is moderately reactive. It oxidizes slowly in air, forming a layer of oxide and nitride that partially protects it. It reacts with water at room temperature (more slowly than alkali metals), producing calcium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Calcium burns in air with an intense reddish-orange flame, producing mainly calcium oxide (CaO) and calcium nitride (Ca₃N₂).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic Mass (u) | Natural Abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium-40 — \(\,^{40}\mathrm{Ca}\,\) | 20 | 20 | 39.962591 u | ≈ 96.94 % | Stable | Ultra-dominant isotope; decay product of potassium-40. |

| Calcium-44 — \(\,^{44}\mathrm{Ca}\) | 20 | 24 | 43.955482 u | ≈ 2.09 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope; used in biomedical research. |

| Calcium-42 — \(\,^{42}\mathrm{Ca}\) | 20 | 22 | 41.958618 u | ≈ 0.647 % | Stable | Minor stable isotope. |

| Calcium-48 — \(\,^{48}\mathrm{Ca}\) | 20 | 28 | 47.952534 u | ≈ 0.187 % | 4.3 × 10¹⁹ years (theoretical) | Radioactive (double β\(^-\)), but half-life so long it is considered stable in practice. Used in nuclear physics to synthesize superheavy elements. |

| Calcium-43, 46 — \(\,^{43}\mathrm{Ca}\), \(\,^{46}\mathrm{Ca}\) | 20 | 23, 26 | 42.958767 u, 45.953693 u | ≈ 0.135 %, 0.004 % | Stable | Rare stable isotopes of calcium. |

| Calcium-41 — \(\,^{41}\mathrm{Ca}\) | 20 | 21 | 40.962278 u | Cosmogenic trace | 103,000 years | Radioactive by electron capture, producing potassium-41. Used to date ancient groundwater. |

| Other isotopes — \(\,^{34}\mathrm{Ca}\) to \(\,^{60}\mathrm{Ca}\) | 20 | 14 — 40 | — (variable) | Non-natural | Milliseconds to days | Unstable isotopes produced artificially; used in experimental nuclear physics. |

N.B. :

Electron shells: How electrons organize around the nucleus.

Calcium has 20 electrons distributed across four electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s², or simplified as: [Ar] 4s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(8) N(2).

K Shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and highly stable.

L Shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M Shell (n=3): contains 8 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶. The 3s and 3p orbitals are complete, forming a stable configuration. Note that the 3d orbitals remain empty.

N Shell (n=4): contains 2 electrons in the 4s subshell. These valence electrons are easily lost during chemical reactions.

The 2 electrons in the outer shell (4s²) are the valence electrons of calcium. This configuration explains its chemical properties:

By losing its 2 electrons in the 4s subshell, calcium forms the Ca²⁺ ion (oxidation state +2), its unique and systematic oxidation state.

The Ca²⁺ ion then adopts an electronic configuration identical to that of argon [Ar], a noble gas, which gives this ion great stability.

The electronic configuration of calcium, with its valence shell containing only 2 electrons in the 4s subshell, classifies it among the alkaline earth metals. This structure gives it characteristic properties: high chemical reactivity (it oxidizes rapidly in air), ability to form ionic bonds by easily giving up its two valence electrons, and exclusive formation of compounds with an oxidation state of +2. Calcium exhibits no coloration in its compounds because the Ca²⁺ ion has no d electrons in partially filled orbitals. Its marked tendency to lose its valence electrons makes calcium an excellent reducing agent and a very reactive metal, particularly with water and oxygen.

Calcium is a reactive metal that primarily forms ionic compounds in the +II oxidation state. It reacts with oxygen to form calcium oxide (CaO), with water to produce calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂, slaked lime), and with acids, releasing hydrogen gas. Calcium reacts at high temperatures with nitrogen (forming Ca₃N₂), sulfur (forming CaS), carbon (forming calcium carbide CaC₂), and halogens. The main compounds of calcium include calcium carbonate (CaCO₃, limestone, chalk, marble), calcium sulfate (CaSO₄, gypsum, plaster), calcium phosphate (Ca₃(PO₄)₂, apatite), calcium chloride (CaCl₂), and calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂). Calcium carbonate dissolves in water containing dissolved carbon dioxide, forming soluble calcium bicarbonate Ca(HCO₃)₂, a fundamental process in the formation of limestone caves and water hardness.

Calcium is the fifth most abundant element in the human body and plays essential biological roles. About 99% of the body's calcium is found in bones and teeth as hydroxyapatite (Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂), the main mineral component of the skeleton, providing rigidity and mechanical strength. The skeleton also serves as a calcium reservoir for the body. The remaining 1%, although minimal in quantity, is absolutely vital: ionic calcium (Ca²⁺) is a universal intracellular messenger involved in muscle contraction, nerve impulse transmission, neurotransmitter release, blood clotting, hormone secretion, enzyme activation, and gene expression regulation. Even minor variations in blood calcium concentration (normally 2.2-2.6 mmol/L) can have serious consequences: hypocalcemia causes cramps, tetany, and cardiac disorders, while hypercalcemia can lead to confusion, arrhythmias, and tissue calcification. In marine organisms, calcium is used to build shells, exoskeletons, and coral reefs. Plants use calcium for cell wall structure and as a secondary messenger in stress responses.

Calcium is the fifth most abundant element in the Earth's crust (about 3.4% by mass). It is a major constituent of many rocks: limestone (pure or impure calcium carbonate), marble (metamorphosed limestone), chalk (biogenic limestone), dolomite (double carbonate of calcium and magnesium), gypsum (hydrated calcium sulfate). Limestone rocks represent about 10% of the continental surface and were formed mainly by the accumulation of marine organism skeletons and shells over millions of years. The calcium cycle is closely linked to the carbon cycle: atmospheric CO₂ dissolves in rainwater, forms carbonic acid that dissolves limestone rocks, and calcium is transported to the oceans where it precipitates again as biological or chemical carbonates. This process of regulating atmospheric CO₂ on a geological scale (millions of years) plays a crucial role in stabilizing the Earth's climate. Limestone caves, stalactites, and stalagmites form through the slow dissolution and reprecipitation of calcium carbonate. Hard water sources contain dissolved calcium from the dissolution of limestone rocks.

Calcium is produced in massive stars during the fusion of silicon in the deep layers just before the supernova explosion. Calcium-40, the dominant isotope, mainly comes from the radioactive decay of potassium-40 in the Earth's crust. Supernovae enrich the interstellar medium with calcium, which is then incorporated into new generations of stars and planets. Calcium has been detected spectroscopically in many stars and nebulae. The absorption lines of ionized calcium (Ca II H and K at 393.3 and 396.8 nm) are among the most intense in stellar spectra and are used to determine the composition and properties of stars. The calcium-48 isotope, extremely neutron-rich, is used in nuclear physics to synthesize superheavy elements (elements 114-118) by fusion with other heavy nuclei. Calcium-aluminum-rich meteorites (CAI inclusions) are among the first solids formed in the early solar system 4.567 billion years ago.

N.B.:

The White Cliffs of Dover, a natural emblem of England, are entirely composed of calcium. These impressive geological formations of white chalk are made of pure calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) formed by the gradual accumulation of microscopic coccolithophore shells, single-celled marine algae, at the bottom of a warm sea during the Cretaceous period about 90 million years ago. Each centimeter of these cliffs represents thousands of years of sedimentation and contains billions of fossilized microorganisms. These cliffs reach up to 110 meters in height and erode at a rate of about 1 cm per year due to waves and weathering. They spectacularly testify to the role of calcium in building monumental geological landscapes from the activity of microscopic organisms over immense geological time scales.