Cadmium was discovered in 1817 almost simultaneously by two chemists working independently on zinc carbonate. The German chemist Friedrich Stromeyer (1776-1835), inspector of pharmacies in the Kingdom of Hanover, analyzed impure zinc carbonate samples that turned yellow upon heating instead of turning white as expected. He succeeded in isolating a new metal, which he named cadmium from the Latin cadmia, the ancient name for calamine (zinc carbonate), itself derived from the Greek kadmeia.

Almost simultaneously, the German chemist Karl Samuel Leberecht Hermann (1765-1846) also discovered cadmium in zinc ores from Silesia, and the French chemist Auguste-Armand de la Rive independently identified it shortly afterward. However, Stromeyer published his results first and received official recognition for the discovery.

Cadmium remained a laboratory curiosity for nearly a century. It was not until the early 20th century that its industrial applications were developed, first as a pigment (cadmium yellow and red), then for electroplating as an anti-corrosion coating, and finally in nickel-cadmium batteries in the 1950s.

Cadmium (symbol Cd, atomic number 48) is a transition metal in group 12 of the periodic table, along with zinc and mercury. Its atom has 48 protons, usually 66 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{114}\mathrm{Cd}\)), and 48 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s².

Cadmium is a shiny, silvery-white metal with a slight bluish tint, resembling zinc in appearance. It has a density of 8.65 g/cm³, making it moderately heavy. Cadmium crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure at room temperature. It is soft, ductile, and malleable, and can be easily cut with a knife and rolled into thin sheets.

Cadmium melts at 321 °C (594 K) and boils at 767 °C (1040 K). These relatively low temperatures facilitate its metallurgical processing. Cadmium has remarkable corrosion resistance in many environments, even superior to zinc in certain conditions (marine and alkaline atmospheres). This property was historically exploited for protective coatings.

A unique property of cadmium is its exceptionally high neutron capture cross-section (about 2500 barns for thermal neutrons), making it an excellent neutron absorber. This property is exploited in the control rods of nuclear reactors to regulate the chain reaction.

Melting point of cadmium: 594 K (321 °C).

Boiling point of cadmium: 1040 K (767 °C).

Cadmium has a very high neutron capture cross-section (2500 barns).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium-106 — \(\,^{106}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 58 | 105.906459 u | ≈ 1.25 % | Stable | Lightest and rarest stable isotope of natural cadmium. |

| Cadmium-108 — \(\,^{108}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 60 | 107.904184 u | ≈ 0.89 % | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope of natural cadmium. |

| Cadmium-110 — \(\,^{110}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 62 | 109.903002 u | ≈ 12.49 % | Stable | Third most abundant stable isotope of natural cadmium. |

| Cadmium-111 — \(\,^{111}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 63 | 110.904178 u | ≈ 12.80 % | Stable | Fourth most abundant stable isotope. Has a nuclear spin used in NMR. |

| Cadmium-112 — \(\,^{112}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 64 | 111.902757 u | ≈ 24.13 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope of cadmium, representing nearly a quarter of the total. |

| Cadmium-113 — \(\,^{113}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 65 | 112.904402 u | ≈ 12.22 % | ≈ 8.04 × 10¹⁵ years | Radioactive (β⁻). Extremely long half-life, considered quasi-stable. Record neutron capture cross-section. |

| Cadmium-114 — \(\,^{114}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 66 | 113.903358 u | ≈ 28.73 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of cadmium, representing more than a quarter of the total. |

| Cadmium-116 — \(\,^{116}\mathrm{Cd}\,\) | 48 | 68 | 115.904756 u | ≈ 7.49 % | ≈ 3.0 × 10¹⁹ years | Radioactive (β⁻β⁻). Extremely slow double beta decay, considered quasi-stable. |

N.B. :

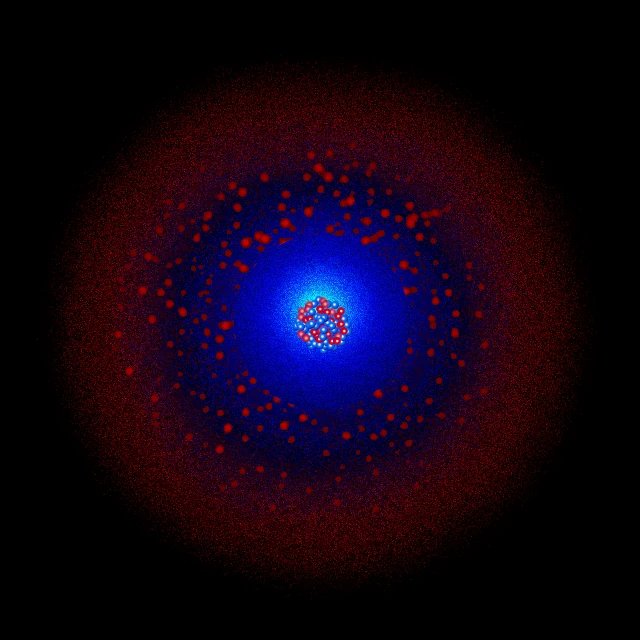

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Cadmium has 48 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s², or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(2).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O shell (n=5): contains 2 electrons in the 5s subshell. These two electrons are the valence electrons of cadmium.

Cadmium has 2 valence electrons in its 5s² subshell. The most common and practically exclusive oxidation state is +2, where cadmium loses its two 5s electrons to form the Cd²⁺ ion with the configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰, which is extremely stable with the complete d subshell.

The +2 state absolutely dominates the chemistry of cadmium and appears in all its important compounds: cadmium oxide (CdO), cadmium chloride (CdCl₂), cadmium sulfide (CdS), and countless coordination complexes. The +1 and 0 oxidation states are extremely rare and only exist in a few highly specialized and unstable compounds. Metallic cadmium corresponds to the oxidation state 0.

Metallic cadmium is relatively stable in dry air at room temperature, slowly forming a protective oxide layer. In humid air or in the presence of carbon dioxide, it tarnishes more quickly, forming a basic carbonate. At high temperatures (above 300 °C), cadmium burns in air with a characteristic yellow-brown flame, forming brown cadmium oxide: 2Cd + O₂ → 2CdO.

Cadmium reacts slowly with dilute acids to form cadmium(II) salts and release hydrogen: Cd + 2HCl → CdCl₂ + H₂. It dissolves more rapidly in oxidizing acids such as nitric acid: 3Cd + 8HNO₃ → 3Cd(NO₃)₂ + 2NO + 4H₂O. Cadmium also reacts with halogens to form cadmium(II) halides.

Cadmium sulfide (CdS) is a particularly important compound, insoluble in water and bright yellow in color. It was historically used as a pigment (cadmium yellow) in artistic paints. Cadmium selenide (CdSe) is also important in optoelectronics as a semiconductor for solar cells and quantum dots.

Cadmium is one of the most toxic heavy metals. It has no known beneficial biological role and is highly toxic to humans, animals, and plants. Exposure to cadmium occurs mainly through inhalation of fumes and dust (industry, smoking) and ingestion (contaminated food, water).

Cadmium accumulates in the body, mainly in the kidneys and liver, with a biological half-life of 10 to 30 years. Chronic exposure causes severe and irreversible kidney damage (renal tubule dysfunction), osteomalacia (softening of the bones), and osteoporosis. Cadmium is classified as a definite carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), primarily causing lung cancer.

Itai-itai disease in Japan, discovered in the 1950s, was caused by chronic cadmium poisoning from rice fields irrigated with water contaminated by mines. This disease caused excruciating bone pain, multiple fractures, and kidney failure. This health tragedy raised global awareness of cadmium toxicity.

Due to its toxicity, the use of cadmium is now strictly regulated in many countries. The European Union has banned cadmium in most applications (RoHS directives), with a few exceptions for critical applications without viable alternatives. Occupational exposure limits are extremely strict (0.01 mg/m³ over 8 hours).

Nickel-cadmium (Ni-Cd) batteries were for decades (1950-2000) the dominant technology for portable rechargeable batteries. Invented in 1899 by the Swede Waldemar Jungner, they reached their peak in the 1980s-1990s for power tools, cordless phones, toys, and professional applications.

Ni-Cd batteries had several advantages: exceptional robustness (up to 1000 charge cycles), performance at low temperatures, high discharge rates, and moderate cost. However, they suffered from the memory effect (loss of capacity if recharged before complete discharge), modest energy density (40-60 Wh/kg), and above all, the toxicity of cadmium.

The advent of nickel-metal hydride (Ni-MH) batteries in the 1990s, followed by lithium-ion batteries in the 2000s, combined with growing environmental concerns, led to the rapid decline of Ni-Cd batteries. The European Union banned portable Ni-Cd batteries in 2009 (Directive 2006/66/EC), except for critical applications (emergency medical equipment, emergency lighting, professional tools).

Today, Ni-Cd batteries represent only a tiny fraction of the rechargeable battery market, confined to a few niches (aviation, railways, backup systems). Global demand for cadmium in batteries has fallen by more than 80% since its peak in the 1990s.

Cadmium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. The eight natural isotopes of cadmium reflect the contributions of these different processes.

The cosmic abundance of cadmium is about 1.6×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This relatively high abundance for a heavy element is explained by the particular nuclear stability of the mass region A ≈ 110-116, where several magic or semi-magic isotopes exist.

Isotopic variations of cadmium in primitive meteorites provide information on the heterogeneity of the solar nebula and the relative contributions of the s and r processes. Some meteorites show anomalies in neutron-rich cadmium isotopes, suggesting variable contributions of r-process materials.

Spectral lines of neutral cadmium (Cd I) and ionized cadmium (Cd II) are observable in the spectra of certain cool stars and giant stars. The analysis of these lines allows the determination of cadmium abundance and traces the chemical enrichment of galaxies over their evolution.

N.B. :

Cadmium is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 0.15 ppm, making it relatively rare, about 1000 times rarer than zinc. Cadmium does not form its own economically exploitable ores but is always associated with zinc in sphalerite ores (zinc sulfide), with typical concentrations of 0.1 to 0.5% cadmium.

Global cadmium production is about 25,000 tons per year, entirely as a by-product of zinc refining. China dominates production with about 80% of the global total, followed by South Korea, Japan, Kazakhstan, and Canada. Cadmium is recovered from the fumes and residues of zinc roasting and electrolysis.

Demand for cadmium has significantly decreased since the 1990s due to regulatory restrictions and the decline of Ni-Cd batteries. The main current application is anti-corrosion coating for aerospace and military (about 30% of demand), followed by pigments (25%, in decline), batteries (20%, in rapid decline), and CdTe solar panels (15%, growing). Cadmium recycling is important, representing about 20% of supply.