Osmium is synthesized in stars mainly through the r-process (rapid neutron capture) that occurs during cataclysmic events such as supernovae and neutron star mergers. As a heavy element with an even atomic number (Z=76), it is efficiently produced by this process. Osmium also has a significant contribution from the s-process (slow neutron capture) in AGB stars (asymptotic giants), but the r-process dominates, accounting for 70-80% of its solar abundance. Osmium is part of the "osmium peak" in the production spectrum of heavy elements by neutron capture.

The cosmic abundance of osmium is about 6.0×10⁻¹³ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms, making it comparable in rarity to platinum and gold, and about 2-3 times rarer than tungsten. Osmium has seven natural isotopes, the most abundant being osmium-192 (41.0%). The isotopic abundances of osmium, particularly the ¹⁸⁷Os/¹⁸⁸Os ratio, are of crucial importance in geochemistry and cosmochemistry.

The rhenium-osmium isotopic system (¹⁸⁷Re → ¹⁸⁷Os) is one of the most important chronological tools for studying the evolution of the Earth and the solar system. Osmium-187 is the radiogenic isotope produced by the beta decay of rhenium-187 (half-life of 41.6 billion years). The importance of this system lies in the marked geochemical differences between these elements: rhenium is moderately siderophile and chalcophile (prefers sulfides), while osmium is strongly siderophile (prefers metal). These differences create significant fractionations during planetary core formation and geological reservoir differentiation.

The Re-Os system is particularly useful for:

The ¹⁸⁷Os/¹⁸⁸Os ratio is considered one of the most sensitive tracers of interaction between the mantle and the Earth's crust.

Osmium takes its name from the ancient Greek ὀσμή (osmḗ), meaning "smell". This name was chosen by its discoverer, Smithson Tennant, because of the pungent and unpleasant odor of osmium oxide (OsO₄), which resembles ozone or chlorine. Osmium shares this etymology with ozone (O₃), which also has a characteristic odor. It is one of the few elements named after a sensory property.

Osmium was discovered in 1803 by the English chemist Smithson Tennant (1761-1815), who also discovered iridium in the same year. Tennant was working on crude platinum from South America, which did not dissolve completely in aqua regia. He noticed that a black insoluble residue remained after treatment. By studying this residue, he identified two new elements: one producing colored salts (which he named iridium, after Iris, the Greek goddess of the rainbow), and the other producing a volatile oxide with a strong odor (which he named osmium).

Early studies on osmium were difficult due to its great hardness, brittleness, and the toxicity of its volatile oxides. The first relatively pure metallic osmium was produced in 1804 by Tennant. However, it was not until the mid-19th century that more effective methods of production and purification were developed. Osmium was one of the last natural elements to be isolated in pure form, due to the technical challenges posed by its properties.

Osmium is one of the rarest natural elements on Earth, with a crustal abundance estimated at about 0.05 ppb (parts per billion). There are no primary osmium mining deposits; it is always recovered as a by-product of the processing of other metals, mainly:

World production of osmium is very low, estimated at less than 1 ton per year. The main producers are South Africa, Russia, Canada, and the United States. Due to its extreme rarity, unique properties, and production difficulty, osmium is one of the most expensive metals, with typical prices of $10,000 to $15,000 per kilogram (or much more for certain forms). Demand is limited by niche applications and availability.

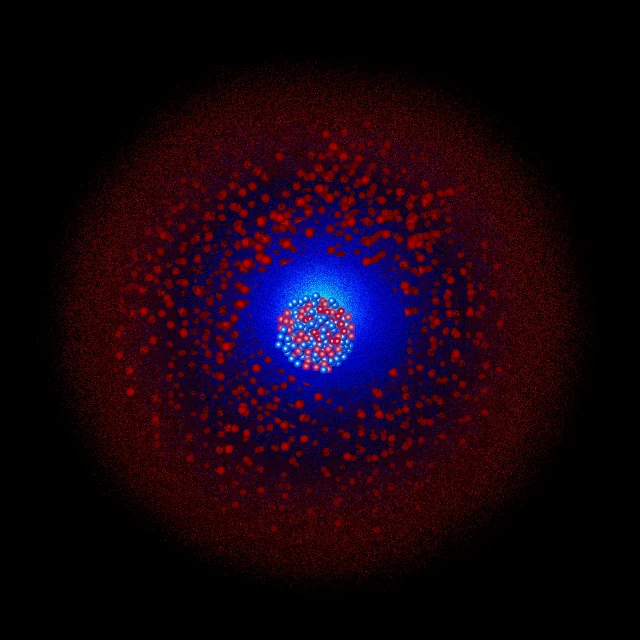

Osmium (symbol Os, atomic number 76) is a transition metal of the 6th period, located in group 8 (formerly VIII) of the periodic table, with iron, ruthenium, and hassium. It belongs to the platinum group metals (platinum, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium, osmium). Its atom has 76 protons, usually 116 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{192}\mathrm{Os}\)) and 76 electrons with the electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁶ 6s². This configuration has six electrons in the 5d subshell and two in the 6s.

Osmium is a bluish-white, shiny, extremely dense, hard, and brittle metal. It holds several records among natural elements:

Osmium has a hexagonal close-packed (HCP) crystal structure at room temperature, which contributes to its high density and hardness.

Osmium melts at 3033 °C (3306 K) - one of the highest melting points among metals - and boils at 5012 °C (5285 K). It has good thermal stability and retains its mechanical properties at high temperatures, although it is generally brittle and difficult to work with.

At room temperature, osmium is relatively inert and resistant to corrosion. However, it forms OsO₄ (osmium tetroxide) at moderate temperatures in the presence of oxygen. OsO₄ is a pale yellow crystalline solid at room temperature, but it sublimes (goes directly from solid to gas) at only 40 °C, producing highly toxic vapors with a characteristic odor. Osmium is attacked by molten alkalis in the presence of oxidants, and dissolves in aqua regia and concentrated nitric acid.

Density: 22.59 g/cm³ - the highest of all natural elements.

Melting point: 3306 K (3033 °C) - among the highest of metals.

Boiling point: 5285 K (5012 °C).

Crystal structure: Hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

Modulus of elasticity: ~550 GPa - extremely stiff.

Hardness: 7.0 on the Mohs scale (pure) - very hard for a metal.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osmium-184 — \(\,^{184}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 108 | 183.952489 u | ≈ 0.02 % | Stable | Lightest stable isotope, very rare in nature. |

| Osmium-186 — \(\,^{186}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 110 | 185.953838 u | ≈ 1.59 % | 2.0×10¹⁵ years | Alpha radioactive with extremely long half-life. Considered stable for most applications. |

| Osmium-187 — \(\,^{187}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 111 | 186.955750 u | ≈ 1.96 % | Stable | Important radiogenic isotope (product of ¹⁸⁷Re), crucial for Re-Os geochronology. |

| Osmium-188 — \(\,^{188}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 112 | 187.955838 u | ≈ 13.24 % | Stable | Reference stable isotope for isotopic measurements (¹⁸⁷Os/¹⁸⁸Os ratio). |

| Osmium-189 — \(\,^{189}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 113 | 188.958147 u | ≈ 16.15 % | Stable | Important stable isotope. |

| Osmium-190 — \(\,^{190}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 114 | 189.958447 u | ≈ 26.26 % | Stable | Most abundant stable isotope in nature. |

| Osmium-192 — \(\,^{192}\mathrm{Os}\,\) | 76 | 116 | 191.961481 u | ≈ 40.78 % | Stable | Major stable isotope, representing about 41% of the natural mixture. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Osmium has 76 electrons distributed over six electron shells. Its electronic configuration [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d⁶ 6s² has a completely filled 4f subshell (14 electrons) and six electrons in the 5d subshell. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(32) P(8), or in full: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 4f¹⁴ 5s² 5p⁶ 5d⁶ 6s².

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to electronic shielding.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. This shell forms a stable structure.

O shell (n=5): contains 32 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p⁶ 4f¹⁴ 5d⁶. The completely filled 4f subshell and the six 5d electrons give osmium its transition metal properties.

P shell (n=6): contains 8 electrons in the 6s² and 5d⁶ subshells.

Osmium effectively has 8 valence electrons: two 6s² electrons and six 5d⁶ electrons. Osmium exhibits a wide range of oxidation states, from -2 to +8, with the +4, +6, and +8 states being the most stable and characteristic.

In the +8 oxidation state, osmium forms OsO₄ (osmium tetroxide), a volatile and highly toxic covalent compound. The +6 state is known in compounds such as OsF₆ (hexafluoride) and osmates(VI). The +4 state is very stable and is found in many compounds such as OsO₂ (osmium dioxide) and osmium(IV) complexes. Osmium also exhibits lower states (+3, +2, +1, 0, -2) in various coordination complexes.

Osmium shares with ruthenium the ability to reach the +8 oxidation state, the highest known for any element along with ruthenium and xenon. This rich oxidation state chemistry, combined with osmium's ability to form multiple bonds with oxygen, halogens, and other ligands, makes it a chemically very interesting element for catalysis and organic synthesis.

At room temperature, metallic osmium is stable in air. However, when heated, it oxidizes to form OsO₄: Os + 2O₂ → OsO₄. This reaction begins at around 200-300 °C. OsO₄ is a pale yellow crystalline solid that sublimes at only 40 °C (goes directly from solid to gas). OsO₄ vapors are extremely toxic, with a characteristic pungent odor that gave the element its name. OsO₄ is a powerful oxidant and reacts with many organic materials.

Metallic osmium is resistant to most cold acids:

Osmium is attacked by molten alkalis in the presence of oxidants, forming soluble osmates.

N.B.:

Aqua regia, from Latin for "royal water", is a corrosive mixture of concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃) and concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl), typically in a 1:3 ratio. Its ability to dissolve gold and platinum, metals resistant to the separate acids, is due to the in situ formation of chlorine (Cl₂) and nitrosyl chloride (NOCl), which oxidize these metals into soluble complex ions (such as [AuCl₄]⁻). Used since alchemical times for the purification of precious metals, it remains crucial in metallurgy, microelectronics, and analytical chemistry.

Osmium reacts with halogens at moderate temperatures to form halides. With fluorine, it forms OsF₆ (hexafluoride, yellow-green liquid) and OsF₄ (tetrafluoride, yellow solid). With chlorine, it forms OsCl₄ (tetrachloride, red-brown solid) and OsCl₃ (trichloride, brown solid). Osmium reacts with sulfur at high temperatures to form OsS₂ sulfide, with phosphorus to form phosphides, and with carbon to form OsC carbide. It also forms silicides, borides, and nitrides.

The most important and dangerous osmium compound is tetroxide (OsO₄). Properties:

Despite its toxicity, OsO₄ is used in electron microscopy to fix and stain biological samples, and in organic synthesis as a selective oxidant.

The most famous application of osmium is its use in ultra-hard alloys, particularly the alloy with iridium. Osmiridium is a natural or synthetic alloy usually containing 30-70% osmium with iridium, and sometimes other platinum group metals. These alloys have exceptional properties:

For most of the 20th century, high-quality fountain pen nibs were made of osmiridium. A small osmiridium ball was welded to the tip of the nib (usually 14 or 18 carat gold) to provide a durable writing surface. These nibs could write millions of words without significant wear. Although ballpoint pens have largely replaced fountain pens for everyday use, high-quality fountain pens still use hard metal alloy nibs (often ruthenium, iridium, or osmium).

Despite its toxicity, OsO₄ is a valuable catalyst in organic synthesis for the asymmetric hydroxylation of alkenes. In the presence of co-oxidants such as N-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMO) or potassium ferricyanide, OsO₄ catalyzes the conversion of alkenes to vicinal diols (glycols) with high stereoselectivity and regioselectivity. This reaction, known as Upjohn or Sharpless hydroxylation (for the asymmetric version), is crucial for the synthesis of many natural and pharmaceutical compounds.

Osmium complexes, particularly those in lower oxidation states, are studied as catalysts for the hydrogenation of olefins, ketones, and other unsaturated compounds. Although less used than ruthenium or rhodium catalysts, some osmium complexes show interesting activity and selectivity for specific reactions.

OsO₄ is used in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as a fixing and staining agent. It fixes biological structures by crosslinking unsaturated lipids and adding electron density (osmium being a heavy element that scatters electrons well). This allows visualization of cell membranes and other lipid structures with high resolution.

Osmium and its alloys are studied for medical implants due to:

However, the high cost and difficulty of processing limit its use to very specialized applications.

Osmium tetroxide (OsO₄) is extremely toxic:

The occupational exposure limit (PEL) for OsO₄ is very low: 0.0002 ppm (0.002 mg/m³) over 8 hours. Extremely careful handling under a fume hood, with full protective equipment, is mandatory.

Pure metallic osmium is much less toxic than OsO₄. Osmium metal dust can cause mechanical irritation but does not have the acute toxicity of OsO₄. Other osmium compounds (halides, lower oxides) have varying toxicities but generally lower than OsO₄.

Waste containing osmium, especially OsO₄, must be handled with extreme caution. OsO₄ is usually reduced to less toxic compounds (such as OsO₂) before disposal. Solid waste containing osmium is often treated as hazardous waste.

Osmium is recycled from:

Recycling is economically attractive due to the high price of osmium, but technically difficult due to the small quantities and dispersion in products. Recycling methods include pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes.

Occupational exposure to osmium occurs mainly in:

Adequate ventilation, chemical hoods, and personal protective equipment (gloves, goggles, respirator if necessary) are essential.