Ruthenium was discovered in 1844 by the Russian chemist Karl Ernst Claus (1796-1864), a professor at the University of Kazan. The history of its discovery is linked to the earlier work of several chemists on platinum ores from the Ural Mountains. In 1828, the Russian chemist Gottfried Wilhelm Osann (1796-1866) had already suggested the existence of several new elements in these ores, which he named pluranium, ruthenium, and polinium, but his work lacked conclusive evidence.

Claus undertook a systematic analysis of the insoluble residues left after dissolving crude platinum in aqua regia. He succeeded in isolating a new metal, which he definitively named ruthenium from the Latin Ruthenia, the medieval name for Russia, paying homage to his homeland. Claus published his detailed results in 1844, unambiguously establishing the properties of ruthenium and its position as the fourth member of the platinum group.

Ruthenium was the last of the six platinum group metals to be discovered, after platinum (known since pre-Columbian South America), palladium (1803), rhodium (1803), osmium (1803), and iridium (1803). These six metals (Ru, Rh, Pd, Os, Ir, Pt) share similar chemical properties and are always found together in natural ores.

Ruthenium (symbol Ru, atomic number 44) is a transition metal in group 8 of the periodic table, belonging to the platinum group metals. Its atom has 44 protons, usually 58 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{102}\mathrm{Ru}\)), and 44 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d⁷ 5s¹.

Ruthenium is a bright, silvery-white, hard, and brittle metal. It has a density of 12.37 g/cm³, making it relatively heavy, although it is the lightest of the platinum group metals. Ruthenium crystallizes in a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) structure at room temperature. It is the hardest transition metal with a Mohs hardness of 6.5, comparable to that of quartz.

Ruthenium melts at 2334 °C (2607 K) and boils at 4150 °C (4423 K). These high temperatures classify it among the refractory metals. Ruthenium has a higher melting point than platinum, palladium, and silver, but lower than those of osmium, rhenium, and tungsten.

Ruthenium is remarkably chemically inert at room temperature, resisting almost all acids, including aqua regia, which dissolves most other metals. This exceptional inertness makes it valuable for applications requiring extreme corrosion resistance.

Melting point of ruthenium: 2607 K (2334 °C).

Boiling point of ruthenium: 4423 K (4150 °C).

Ruthenium is the hardest transition metal with a Mohs hardness of 6.5.

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruthenium-96 — \(\,^{96}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 52 | 95.907598 u | ≈ 5.54 % | Stable | Lightest and rarest stable isotope of natural ruthenium. |

| Ruthenium-98 — \(\,^{98}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 54 | 97.905287 u | ≈ 1.87 % | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope of natural ruthenium. |

| Ruthenium-99 — \(\,^{99}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 55 | 98.905939 u | ≈ 12.76 % | Stable | Third most abundant stable isotope. Transmutation product of technetium-99. |

| Ruthenium-100 — \(\,^{100}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 56 | 99.904219 u | ≈ 12.60 % | Stable | Fourth most abundant stable isotope of natural ruthenium. |

| Ruthenium-101 — \(\,^{101}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 57 | 100.905582 u | ≈ 17.06 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope of natural ruthenium. |

| Ruthenium-102 — \(\,^{102}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 58 | 101.904349 u | ≈ 31.55 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of ruthenium, representing nearly one-third of the total. |

| Ruthenium-104 — \(\,^{104}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 60 | 103.905433 u | ≈ 18.62 % | Stable | Third most abundant isotope of natural ruthenium. |

| Ruthenium-106 — \(\,^{106}\mathrm{Ru}\,\) | 44 | 62 | 105.907329 u | Synthetic | ≈ 373.6 days | Radioactive (β⁻). Important fission product. Used as a beta radiation source in ophthalmology. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

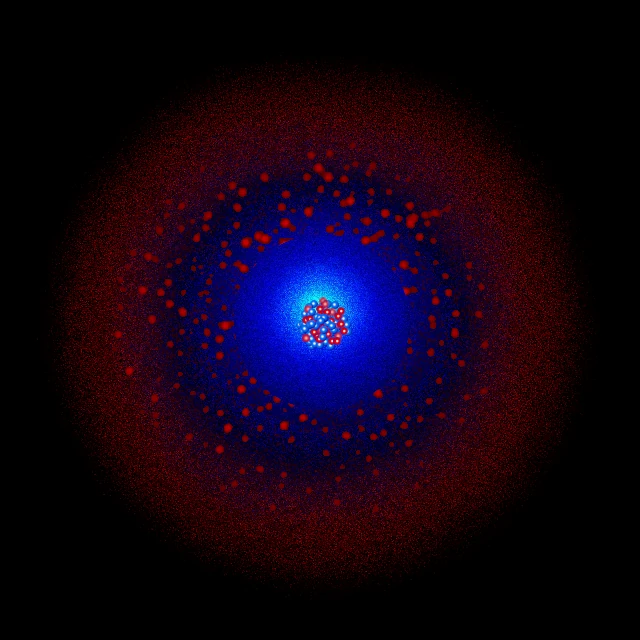

Ruthenium has 44 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its full electronic configuration is : 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁷ 5s¹, or simplified: [Kr] 4d⁷ 5s¹. This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(15) O(1).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 15 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d⁷. The seven 4d electrons are valence electrons.

O shell (n=5): contains 1 electron in the 5s subshell. This electron is also a valence electron.

Ruthenium has 8 valence electrons: seven 4d⁷ electrons and one 5s¹ electron. Ruthenium exhibits a wide range of oxidation states from -2 to +8, although states +2, +3, and +4 are the most common. The +8 state in ruthenium tetroxide (RuO₄) is the highest of all elements after osmium.

The +3 oxidation state is particularly stable in aqueous solution, forming various ruthenium(III) complexes. The +4 state appears in ruthenium dioxide (RuO₂), a black conductive oxide used in electronics. Ruthenium tetroxide (RuO₄), state +8, is a volatile yellow-gold compound, a powerful oxidant, and toxic, similar to osmium tetroxide.

Ruthenium is one of the most chemically inert metals. At room temperature, it is practically unattacked by all acids, including aqua regia, concentrated sulfuric acid, and nitric acid. This exceptional resistance is due to a very stable protective oxide layer that forms spontaneously on the metal's surface.

Ruthenium begins to oxidize significantly above 800 °C in air, forming ruthenium dioxide (RuO₂). At even higher temperatures in the presence of oxygen or powerful oxidants, it can form volatile ruthenium tetroxide (RuO₄): Ru + 2O₂ → RuO₄. The tetroxide sublimes easily and gives off a characteristic pungent odor.

Ruthenium can be dissolved by fusion with alkaline hydroxides in the presence of oxidants, forming ruthenates. Gaseous chlorine at high temperature also attacks ruthenium, forming ruthenium trichloride (RuCl₃), a brown-black hygroscopic compound widely used as a precursor for the synthesis of ruthenium complexes.

Ruthenium forms an extremely rich coordination chemistry with virtually all types of ligands. Ruthenium complexes exhibit a wide variety of structures and electronic properties, exploited in catalysis, photochemistry, and medicine. Ruthenium also forms organometallic compounds with cyclopentadienyl, arene, and carbonyl ligands.

Ruthenium plays a major role in modern homogeneous catalysis. In 2005, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Yves Chauvin, Robert H. Grubbs, and Richard R. Schrock for the development of olefin metathesis, a revolutionary chemical reaction that reorganizes carbon-carbon double bonds in organic molecules.

Grubbs catalysts, based on ruthenium complexes with carbene ligands, have revolutionized organic synthesis. These ruthenium catalysts are remarkably stable, tolerate a wide variety of functional groups, operate at room temperature, and are compatible with air and moisture. First- and second-generation Grubbs catalysts are now standard tools in organic chemistry laboratories worldwide.

Ruthenium-catalyzed metathesis is widely used in the pharmaceutical industry to synthesize complex molecules, in the polymer industry to produce advanced materials, and in green chemistry to develop more efficient and less polluting processes. This discovery illustrates how a rare metal can have a considerable impact on modern chemistry and industry.

Ruthenium complexes are generating increasing interest in medicine, particularly as alternative anticancer agents to cisplatin. Unlike platinum, ruthenium exhibits lower systemic toxicity and different mechanisms of action, potentially capable of overcoming resistances developed against platinum-based drugs.

Several ruthenium compounds have reached human clinical trial phases. NAMI-A (imidazolium trans-imidazole-dimethylsulfoxide-tetrachlororuthenate) and KP1019 (indazolium trans-tetrachlorobis(1H-indazole)ruthenate(III)) have shown promising results against metastases and certain resistant cancers. These complexes exploit the multiple oxidation states of ruthenium and its ability to form bonds with DNA and proteins.

Ruthenium polypyridine complexes are also being studied for cancer photodynamic therapy. These compounds absorb visible light and generate reactive oxygen species that selectively kill tumor cells. This approach combines coordination chemistry, photochemistry, and oncology, illustrating the multidisciplinary biomedical applications of ruthenium.

Ruthenium is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. The seven stable isotopes of ruthenium reflect the contributions of these different nucleosynthesis processes.

The cosmic abundance of ruthenium is about 1.8×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This relatively high abundance for a platinum group metal is explained by its favorable position in the nuclear stability curve and by favorable neutron capture cross-sections in the s and r processes.

Isotopic variations of ruthenium in primitive meteorites provide valuable information on the heterogeneity of the early solar system and the relative contributions of s and r processes. Some meteorites show excesses in neutron-rich ruthenium isotopes (Ru-100, Ru-104), suggesting variable contributions of s and r process materials in different regions of the solar nebula.

Spectral lines of neutral (Ru I) and ionized (Ru II) ruthenium are observable in the spectra of many cool stars and giant stars. The analysis of these lines allows the determination of ruthenium abundance and the tracing of the chemical enrichment of galaxies. Excesses of ruthenium have been detected in certain carbon stars enriched in s-process elements.

N.B.:

Ruthenium is extremely rare in the Earth's crust with an average concentration of about 0.001 ppm (1 part per billion), about 1000 times rarer than gold. It does not form its own minerals but is always associated with other platinum group metals in native platinum ores and alluvial deposits derived from ultramafic rocks.

The main ruthenium deposits are found in South Africa (Bushveld Complex, about 80% of world reserves), Russia (Ural Mountains and Siberia), Canada (Sudbury), the United States (Montana), and Zimbabwe. Global ruthenium production is about 30 to 40 tons per year, mainly as a by-product of nickel and platinum refining.

Ruthenium is extracted from platinum group metal concentrates through complex hydrometallurgical processes involving dissolution in aqua regia, separation by selective precipitation or liquid-liquid extraction, and final purification by distillation of ruthenium tetroxide (RuO₄). The price of ruthenium varies widely depending on industrial demand, typically ranging from 200 to 500 dollars per troy ounce (31.1 grams), or about 6000 to 15000 dollars per kilogram, much cheaper than platinum, palladium, or rhodium.