Tin is one of the metals known since ancient times, used by humanity for at least 5000 years BCE. Its discovery and exploitation marked a major turning point in human history: the Bronze Age (approximately 3300-1200 BCE). The alloy of copper (about 90%) and tin (about 10%) produced bronze, a revolutionary material much harder and more durable than pure copper, transforming weaponry, agriculture, and craftsmanship.

Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Indus Valley civilizations mastered bronze metallurgy as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. Tin deposits were rare and precious, creating extensive trade routes. The mines of Cornwall in England, exploited since antiquity, supplied tin to the Phoenicians and Romans, becoming legendary. Control over tin sources conferred a considerable strategic advantage.

The name tin comes from the Latin stannum, which originally referred to an alloy of silver and lead before designating pure tin. The chemical symbol Sn comes directly from the Latin stannum. In English, tin derives from Old English and Germanic, reflecting the importance of this metal in ancient European cultures.

Although known for millennia, tin was only recognized as a distinct chemical element in the 18th century, with the development of modern chemistry. Antoine Lavoisier included it in his list of chemical elements published in 1789, consolidating its scientific recognition.

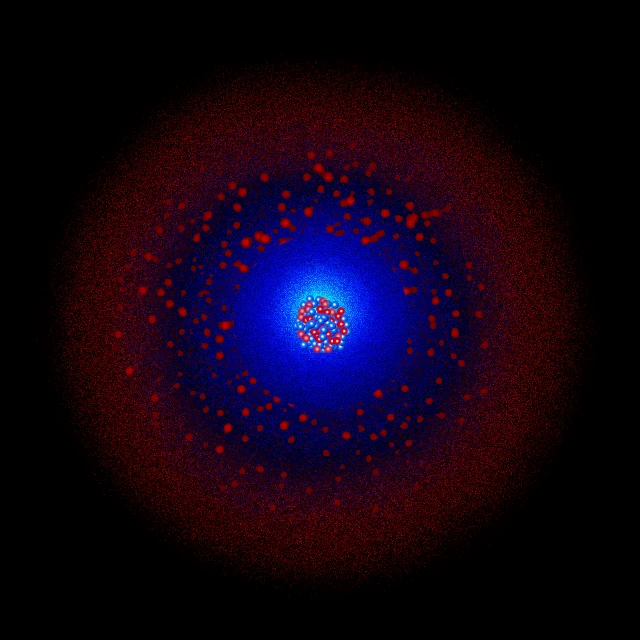

Tin (symbol Sn, atomic number 50) is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table, along with carbon, silicon, germanium, and lead. Its atom has 50 protons, usually 70 neutrons (for the most abundant isotope \(\,^{120}\mathrm{Sn}\)) and 50 electrons with the electronic configuration [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p².

Tin is a bright silvery-white metal, soft and malleable. It has a density of 7.31 g/cm³ in its stable β form (white tin). Tin exhibits two main allotropic forms with radically different properties: α-tin (gray tin) and β-tin (white tin), separated by a transition temperature of 13.2 °C.

White tin (β-Sn), stable above 13.2 °C, is metallic, ductile, and malleable, crystallizing in a tetragonal structure. This is the form used in all practical applications. Gray tin (α-Sn), stable below 13.2 °C, is a gray, powdery, and brittle semiconductor, crystallizing in a diamond cubic structure similar to silicon. The transformation of white tin to gray tin at low temperatures, accompanied by a 27% volume expansion, is called "tin pest" or "tin disease."

White tin melts at 232 °C (505 K) and boils at 2602 °C (2875 K). Its relatively low melting point facilitates its use in solders and low-melting alloys. Tin resists corrosion by fresh water and seawater well but is attacked by strong acids and bases.

Melting point of tin: 505 K (232 °C).

Boiling point of tin: 2875 K (2602 °C).

Transition temperature α-Sn → β-Sn: 286 K (13.2 °C).

| Isotope / Notation | Protons (Z) | Neutrons (N) | Atomic mass (u) | Natural abundance | Half-life / Stability | Decay / Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tin-112 — \(\,^{112}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 62 | 111.904818 u | ≈ 0.97 % | Stable | Lightest and rarest stable isotope of natural tin. |

| Tin-114 — \(\,^{114}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 64 | 113.902779 u | ≈ 0.66 % | Stable | Second rarest stable isotope of natural tin. |

| Tin-115 — \(\,^{115}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 65 | 114.903342 u | ≈ 0.34 % | Stable | Third rarest stable isotope. Used in NMR spectroscopy. |

| Tin-116 — \(\,^{116}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 66 | 115.901741 u | ≈ 14.54 % | Stable | Fourth most abundant stable isotope of natural tin. |

| Tin-117 — \(\,^{117}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 67 | 116.902952 u | ≈ 7.68 % | Stable | Fifth most abundant stable isotope of natural tin. |

| Tin-118 — \(\,^{118}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 68 | 117.901603 u | ≈ 24.22 % | Stable | Second most abundant isotope of tin, representing nearly a quarter of the total. |

| Tin-119 — \(\,^{119}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 69 | 118.903308 u | ≈ 8.59 % | Stable | Sixth most abundant stable isotope. Used in Mössbauer spectroscopy. |

| Tin-120 — \(\,^{120}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 70 | 119.902194 u | ≈ 32.58 % | Stable | Most abundant isotope of tin, representing nearly one-third of the total. |

| Tin-122 — \(\,^{122}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 72 | 121.903439 u | ≈ 4.63 % | Stable | Seventh most abundant stable isotope of natural tin. |

| Tin-124 — \(\,^{124}\mathrm{Sn}\,\) | 50 | 74 | 123.905274 u | ≈ 5.79 % | Stable | Eighth and last stable isotope. Heaviest stable isotope of tin. |

N.B.:

Electron shells: How electrons are organized around the nucleus.

Tin has 50 electrons distributed over five electron shells. Its complete electronic configuration is: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰ 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p², or simplified: [Kr] 4d¹⁰ 5s² 5p². This configuration can also be written as: K(2) L(8) M(18) N(18) O(4).

K shell (n=1): contains 2 electrons in the 1s subshell. This inner shell is complete and very stable.

L shell (n=2): contains 8 electrons distributed as 2s² 2p⁶. This shell is also complete, forming a noble gas configuration (neon).

M shell (n=3): contains 18 electrons distributed as 3s² 3p⁶ 3d¹⁰. This complete shell contributes to the electronic screen.

N shell (n=4): contains 18 electrons distributed as 4s² 4p⁶ 4d¹⁰. The complete 4d subshell is particularly stable.

O shell (n=5): contains 4 electrons distributed as 5s² 5p². These four electrons are the valence electrons of tin.

Tin has 4 valence electrons: two 5s² electrons and two 5p² electrons. The two main oxidation states are +2 and +4. The +4 state, where tin loses its four valence electrons to form the Sn⁴⁺ ion, is the most stable and appears in most compounds: tin dioxide (SnO₂), tin tetrachloride (SnCl₄), and organotin compounds.

The +2 state, where tin loses only its two 5p² electrons (inert pair effect), becomes progressively more stable down group 14. Compounds such as tin(II) oxide (SnO) and tin(II) chloride (SnCl₂) are common but tend to oxidize to tin(IV) compounds. Tin(II) chloride is a powerful reducing agent used in chemical synthesis.

Tin is relatively stable in air at room temperature, slowly forming a thin protective oxide layer that prevents further corrosion. This corrosion resistance explains its historical and modern use in protecting other metals (tinplate). Tin resists fresh water, seawater, and many organic compounds well.

Tin reacts with strong acids to form tin(II) or tin(IV) salts depending on the conditions: Sn + 2HCl → SnCl₂ + H₂ (dilute acid), or Sn + 4HNO₃ → Sn(NO₃)₄ + 2NO₂ + 2H₂O (concentrated nitric acid). Strong bases also attack tin, forming stannates: Sn + 2NaOH + 4H₂O → Na₂[Sn(OH)₆] + 2H₂.

Tin reacts with halogens to form tetrahalides (state +4): Sn + 2Cl₂ → SnCl₄. Tin tetrachloride is a fuming liquid used in organic synthesis. Tin also forms many organotin compounds (R₄Sn, R₃SnX, etc.) widely used as catalysts, PVC stabilizers, and biocides, although their toxicity has led to usage restrictions.

The dominant modern application of tin, representing about 50% of global demand, is in electronic solders. For decades, the tin-lead alloy (typically 63% Sn, 37% Pb) was the standard solder in electronics, with a melting point of 183 °C and excellent wetting properties.

Awareness of lead toxicity and its environmental impacts led to the adoption of strict regulations, notably the European Union's RoHS (Restriction of Hazardous Substances) directive in 2006, banning lead in most electronic equipment. This regulation triggered a technological revolution: the transition to lead-free solder.

Lead-free solders are primarily based on tin with various additives. The most common alloys are SAC (tin-silver-copper: 96.5% Sn, 3% Ag, 0.5% Cu) with a melting point of 217-220 °C, and Sn-Cu (99.3% Sn, 0.7% Cu) for lower-cost applications. This transition required a complete overhaul of electronic manufacturing processes, with higher soldering temperatures and long-term reliability challenges.

Global tin demand for solder has surged with this transition, increasing from about 50,000 tons/year in the 1990s to over 180,000 tons/year in the 2020s. Each smartphone contains about 0.5-1 gram of tin in its solder, each laptop 3-5 grams, creating massive demand driven by the proliferation of consumer electronics.

Tinplate, steel sheet coated with a thin layer of tin (typically 2-10 microns), revolutionized food preservation in the 19th century. Nicolas Appert invented canning in 1810, and Peter Durand patented the tin can in 1810. This innovation enabled long-term food preservation, transforming food, trade, and military logistics.

The tin coating protects steel from corrosion and prevents the migration of metal ions into food. Tin is non-toxic, chemically inert with most foods, and forms an effective protective barrier. Although aluminum and plastic have gradually replaced tinplate for some applications, tin cans remain widely used, accounting for about 15-20% of global tin demand.

Tin is synthesized in stars mainly through the s-process (slow neutron capture) in asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, with contributions from the r-process (rapid neutron capture) during supernovae and neutron star mergers. Tin has the largest number of stable isotopes (10) of any element, reflecting the particular nuclear stability of nuclei with 50 protons (magic number).

The cosmic abundance of tin is about 4×10⁻⁹ times that of hydrogen in number of atoms. This relatively high abundance for a heavy element is explained by the exceptional nuclear stability of the nucleus with Z=50 (complete proton magic shell), favoring the formation and survival of tin isotopes during nucleosynthesis processes.

The ten stable isotopes of tin are produced by different combinations of the s, r, and p (proton capture) processes, each dominating for certain isotopes. Analysis of tin isotopic ratios in primitive meteorites provides valuable constraints on the relative contributions of these processes to the composition of the solar system and on the heterogeneity of the primitive solar nebula.

Spectral lines of neutral tin (Sn I) and ionized tin (Sn II) are observable in the spectra of certain cool stars and giant stars enriched in heavy elements. Analysis of these lines allows the determination of tin abundance and traces the chemical enrichment of galaxies, confirming the role of AGB stars in the production of s-process elements.

N.B.:

Tin is present in the Earth's crust at an average concentration of about 2 ppm, making it relatively rare, about 1000 times rarer than zinc but 40 times more abundant than silver. The main tin ore is cassiterite (SnO₂), containing about 78% tin, usually in the form of hydrothermal veins or alluvial deposits (placers).

Global tin production is about 350,000 tons per year. China dominates production with about 40% of the world total, followed by Indonesia (20%), Myanmar (15%), Peru (7%), and Bolivia. The historic deposits of Cornwall have been exhausted since the 20th century, but mining continues in Southeast Asia and South America.

Tin recycling is significant, accounting for about 30% of annual supply. Tin is recovered mainly from used tinplate (electrolytic or chemical detinning), slag, and foundry residues, and from electronic waste. The high recycling rate of tin is due to its economic value, ease of recovery, and environmental concerns. Tin is not considered a critical material by most countries due to sufficient reserves and diverse sources.